It’s not just about empathy. It’s about bending time. It’s about giving yourself more lives, you know? It’s about being in the shoes of someone that isn’t you.

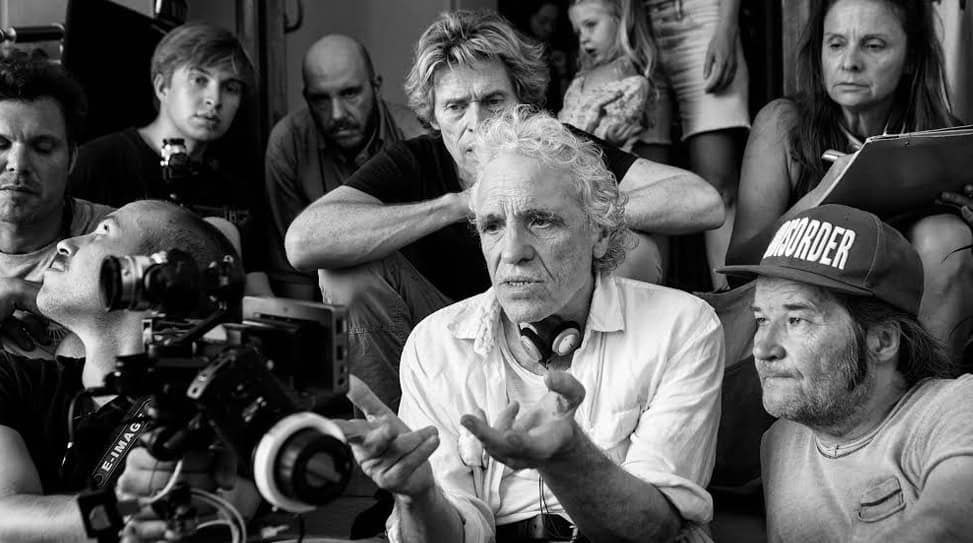

With over a hundred film performances to his name, Willem Dafoe is not only one of the most prolific actors of our time but also the most gifted. He’s that rare breed of actor who shifts effortlessly between lead and character parts, and equally powerful in either, also situating him as one of the wiliest and most resourceful. Having worked together since the turn of the millennium, first with New Rose Hotel (1998), maverick filmmaker Abel Ferrara casts his long-time muse as his surrogate in Tommaso, a tale of an aging filmmaker who’s tormented by his demons. The film, which premiered at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, is the first scripted drama in five years from Ferrara, which occupies the genre of confessional, semi-autobiographical films based on its very creators. Tommaso is arguably one of Ferrara’s most personal works to date by some measures.

Starring opposite Ferrara’s real-life spouse and toddler daughter, and filmed in the writer-director’s Rome apartment, Dafoe disappears into his titular character, an American moviemaker living abroad in the Italian capital. Unfolding across a short summer period, the film’s early passages linger attentively on the everyday textures of his existence. We shadow Tommaso as he performs quotidian tasks on the day-to-day, wandering from coffee shops to acting workshops, from support group meetings for addict expats and back to his home, where he tinkers away at a new screenplay, one that’s believed to be Ferrara’s real-life, long-gestating follow-up feature to Tommaso: Siberia, which premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival earlier this year. Meanwhile, Tommaso’s much younger wife, Nikki (Cristina Chiriac), tackles most of their parenting duties looking after little Deedee (Anna Ferrara). At first glance, it’s homespun paradise, and the most wholesome Dafoe has ever been on screen. But the film’s tranquil rhythms soon convulse as Tommaso begins to clash with Nikki in their tight quarters. The very fear of losing his family is what threatens to drive them away. And underneath Tommaso’s sober manners is a lifetime of drug use. The man’s temptations emerge as stray fantasies that continually hijack his mind. Sometimes erotic, at other times cataclysmic, Ferrara’s vision of Tommaso is that of an artist constantly tortured by his cravings, and similarly his earnest desire for the simple pleasures of a mundane domesticity.

Dafoe doesn’t simply show up here. He burrows deep inside the role, which is believed to have been heavily improvised. Needless to say, he has always been reliable. At 64, his wrinkled but still chiseled face is a road map of agony and ecstasy that transcends the screen to our viewing pleasures. Like almost everything else he has done, Tommaso is a magnetic portrayal with Dafoe on a spectrum of uncontrolled rage and frayed anguish. Tommaso is the multiple Oscar nominee’s fifth collaboration with Ferrara, and Siberia marks their sixth creative partnership. The duo appear to be anything but each other’s most rejuvenating collaborators in their late periods, respectively.

Tommaso is now available to view at virtual cinema platforms via Kino Marquee.

I’m a big fan of Tommaso. I hope this Dafoe-Ferrara collaboration never ends. You guys always take it to such compelling places, and I find it very rejuvenating.

[laughs] Great. Thank you, thank you.

Abel had this to say about your longstanding creative partnership: “With any relationship, it either ends or it gets better.” He was of course implying that it’s the latter with you guys. When did you first know that this might be a professional relationship and a friendship that would be lasting and meaningful? Does it go all the way back to New Rose Hotel?

Yes and no. I mean, that’s where it started. But I knew Abel before New Rose Hotel, and many times he tends to cast a pretty wide net casting-wise. I remember on films like King of New York and Bad Lieutenant, in those days he would kind of put feelers out to a lot of actors believe it or not. So I knew him in that respect, but never from the right thing to do with him or the right moment to do something in one of his films. Of course he was well-known in the downtown New York scene, and it was really New Rose Hotel where we first met. Actually, that was kind of a mixed experience. Not judging the film, but that was pre-sobriety. That was a scripted piece. It felt slightly more conventional in our approach. Of course Tommaso is I think the fifth or the sixth [collaboration] or something like that, and by that time we knew each other pretty well and we could work from basically a scenario. Not all the scenes, but a lot of scenes were just totally improvised. He would basically tell me a story or tell me a situation and then we’d go into it. The camera was so fluid that it could go with us wherever we wanted to go. We worked with such a small crew, guerrilla style, that we were very light on our feet. That was real satisfying because of course it’s a very small production and the shoot was very brief actually, but it felt very freeing in the respect that every day you never knew exactly what was going to happen and you were in the search of something. The elements that we were using we were all quite familiar with so there was an authority in the pretending there and in the making, the improvisation. But it wasn’t oppressive. We never knew exactly what the scenes had to do in the course of the film, how it would be structured or where we were taking these people, where we were taking the characters. That’s a little less true in the flashback scenes that are a little more structured and I probably have less driving to do in those. It would get set up and we would execute more like a traditional scene. But the other ones were incredibly loose. That’s not the way I want to work all the time, but in this case I think it was the appropriate way to work with this material.

Taking the scene with the homeless man who Tommaso confronts for causing a raucous in the neighborhood as an example, I understand that you never met the guy prior to doing those takes. What are your parameters when you’re asked to enter an uncertain space like that as a performer? There must be some trepidation on your part.

You know, it’s challenging. It’s also a film where I’m speaking in Italian, a language that I do speak but I’m not fluent in. There’s lots of challenges, but I find that the more challenges you have, if you’re really sincere and you’re really committed and really involved in the material, then even crashing is okay. [laughs] You throw yourself into it and it finds its own rhythm, it finds its own way. That’s a good example because I hadn’t met the guy before. We did have one plan, one idea about where to take it. You have certain ideas about where you think you might want to take the scene, but he’s not an actor. He’s a homeless guy. The basic setup of the scene is something that happened in real life. Abel—we—found him and basically it was a reenactment of something that had happened. That’s where it starts, then it goes in a completely different place because the circumstances are different. We interact and, as I say, he’s not an actor so he’s just doing whatever he feels like doing. It’s a meeting, you know? Just to give you an example of the kind of improvisation [we were working with], another scene that I really had trouble with was when I walk the girl home from the AA meeting. No discussion at all. We didn’t know what we were going to talk about at all. We only knew that we were just gonna go from the AA meeting to the apartment, and I was gonna drop her off. We didn’t even know whether I was gonna go home with her or not. That was fun because it’s an experience, you know? Then you aren’t sending a message home, you aren’t interpreting. You’re just pretending and playing around with the scenario.

You’ve previously said that, more often, people think improvisation means coming up with clever dialogue. But in reality it’s about immersing yourself in situations. Embodying them.

I think that’s true. I still believe that, yes.

There’s a scene in the film where Tommaso is teaching an acting class. You have experience teaching workshops and masterclasses yourself. Are the ideas and methods that Tommaso imparts on his students the same ones you prescribe to as an actor?

Some yes, some no. I’m not a teacher, but I have taught some classes. I basically like to get in a room and talk to the students and kind of play games and dance around and do some exercises to get them loose and try out some things that are in my head. I’ve got no methodology. But yes, that wasn’t kind of improvised or partly improvised. No, it’s totally improvised. [laughs] Those students show up and I know that my job is to give them a class for a couple hours, and that’s what we do. The camera is so fluid that [cinematographer] Peter Zeitlinger was, you know, my shadow. I mean, I was aware of him, but often I could forget about him. Sometimes I would work with him very closely, like when we’re getting in that elevator in the building, for example. It’s very tricky to do that naturally. But anyways, for the acting class, some of that stuff was made up, some of that stuff I’ve used before, some of that stuff I believe in and some of that stuff I maybe don’t. I was just trying to teach, that was my action, and I was trying to have fun with those students and try to find something out.

You must field a lot of questions about whether you’re portraying Abel in Tommaso. Abel has gone on the record to say that he doesn’t see himself when he watches Tommaso. Do you see much of yourself, or Abel for that matter, when you watch the movie?

Ha! You know, I still never see myself. I really don’t. I mean, it looks like me and some things sound like me and some things feel like natural behavior and, because there is improvisation sometimes, I’m saying things I could say in real life. So there’s not a big mask. There’s not a big character there. We’re stitching together things that we know, things that we don’t know, things that are around us. I don’t think so much about how much is Abel and how much is me. I also don’t like to talk about that in front of an audience because that’s not really what it’s about. But clearly, if you bent that way and you really are burning with curiosity, of course anytime we do any character, it’s a mix. Somewhat fundamentally, you try to get rid of yourself so you can make room to inhabit another person. But at the same time, your way of getting there means sometimes you have to lean on certain things you do know. In this case, because we are working with a creative family and we are working in our neighborhood and we are dealing with non-actors and strangers sometimes on the street—yeah, I don’t see myself in it so much.

Is it safe to assume that the film Tommaso is prepping in the movie is in fact Siberia?

I’d say that’s really correct. [laughs] We’re dealing with what’s around us. Abel and I were preparing Siberia when we were shooting Tommaso. When I go back to that part of Rome and he wants me to be working on something, that’s the most natural thing to do. So we use that.

How did the two films overlap for you in terms of your character? Did it overlap for you?

I don’t think so much about character and I don’t think so much about story. I think about an experience and putting myself in a place where I have an experience where I learn something and something happens and then you order the ideas in a way that they can be shared. Hopefully, it can let viewers experience something they don’t know. It can change their minds. They can feel things from a different point of view. It’s not just about empathy. It’s about bending time. It’s about giving yourself more lives, you know? It’s about being in the shoes of someone that isn’t you.

Abel has said that he wouldn’t have made this film had you not been on board. I really believe him when he says that. It also strikes me how often he describes his filmmaking as a “game.” He likens his work to art experiments—not products. That must be attractive to you, and maybe it’s different to how the work is perceived in your other collaborations.

I would say that’s accurate just because we’re working on lower-budget levels and we’re working looser. We’re flying under the radar. We’re using what’s around us. Tommaso is a very homemade movie. With our collaboration, he starts spitballing ideas and pieces of script or images or ideas with me very early. I go off and do other things, he goes off and does other things, but we’re always working on something together. So in that respect, it is a family and it is a family that extends to also some degree my wife and other filmmakers in this neighborhood and other actors and people he’s worked with before. It’s nice. I think I like that because, you know, I come from a theatre background. For almost 30 years, I went to theatre and worked with basically the same people. I believe in the strength of working with people that you know well, people that you care about. You can’t do it all the time and you won’t want to do it all the time, but when you do, there’s a real pleasure. Everything is made with a lot of love, with a lot of care and a lot of understanding, and that’s nice. And once again, I don’t want to always work that way. But when I can work that way, it’s really nice.

What did Abel have in mind for Tommaso at the very beginning?

He just told me some scenes he wanted to see, you know? He wanted to have an AA meeting. He had some ideas of flashbacks. He wanted to deal with some tension in a marriage. He wanted to deal with taking his daughter to the park. Just little fragments and then we developed it from there.

Life seems to be the source of everything.

I’d say especially for him because he deals with what’s around him. One of the things I love about Abel is that he’s a self-starter. He doesn’t wait. He has to make things. He likes shooting. He likes to be making something. So there’s not a preciousness. It’s also not psychotherapy. He loves film language. He loves cinema. He loves being in a group making something. Basically, he’s expressing what he loves or what he encounters in his life, you know?

I’m very curious about your life in Rome, especially after having watched Tommaso. What are you getting out of Rome these days? How is Rome inspiring you?

Well, I’ve lived here for a long time. It’s where my wife is from. When I’m working, I split my time between New York and Rome. Rome has its impact on me because here I’m a different person. I’m an immigrant. I’m someone that’s learning the language. I feel like I’m a different person than when I’m in New York. How does it affect my relationship to what my profession is? Is there a difference? It’s nice to mix it up. It’s good when your identity isn’t so fixed. It’s something you have to protect. I think Rome affords me that. It’s really a nice place to disappear.

Clarion Call: Garrett Hedlund

Clarion Call: Garrett Hedlund A Conversation with Simon Baker

A Conversation with Simon Baker

No Comments