Being closed off to experiences is not the way to deal with things. Life is about engaging and also about the compromise.

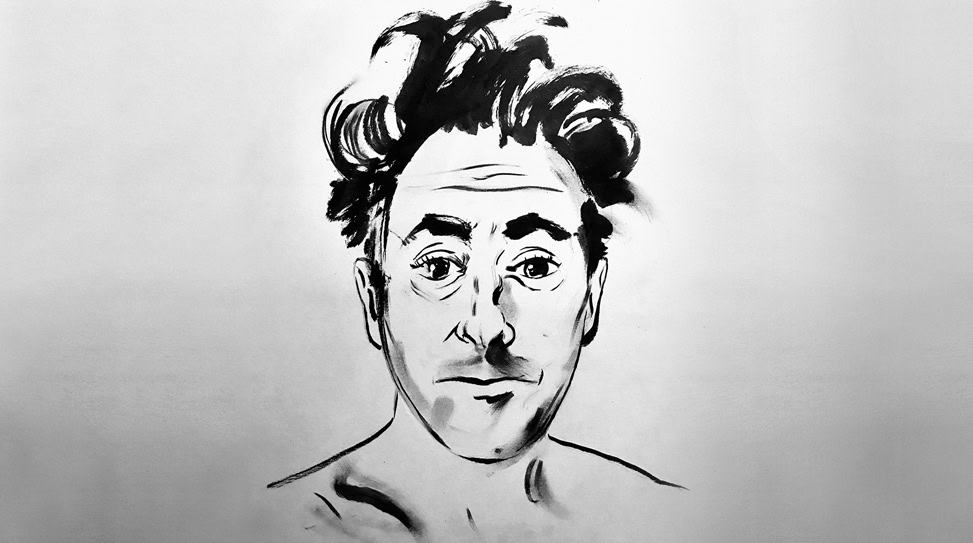

Alan Cumming has accumulated many, many hyphens to his name over the past several decades—impressive life moments even in the realm of celebrity. He had his own talk show. He voiced a Smurf—twice. He recorded a duet with his good friend Liza Minelli. He appeared in a JAY-Z video. He wrote a #1 New York Times best-selling memoir, and more recently, released a children’s picture book with his husband. Here’s an oxymoron: He launched a so-called “anti-celebrity” fragrance named Cumming. He was on a postal stamp. Beyond his acting work in film and TV for which he has received Golden Globe, People’s Choice, Emmy and SAG Award nominations, he’s also a Tony winner. He owns a bar in New York’s East Village aptly named Club Cumming. His activism earned him countless humanitarian awards. He isn’t nearly finished yet.

So where does Cumming start and Cumming end? There’s much—too much—to talk about, including his new film After Louie. Thanks to the activists behind ACT UP (The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), being HIV-positive is no longer an automatic death sentence. But what happened to the survivors of the initial wave of the AIDS crisis—members of the lost generation we never lost? This is the burning question at the heart of After Louie, directed by original ACT UP member Vincent Gagliostro. Racked with survivor’s guilt and grieving the death of his friend who succumbed to the AIDS epidemic, Sam (Cumming) expends all of his energy into making a documentary on the subject. When he meets a much younger Braeden (Zachary Booth) at a bar one night, casual sex soon turns to intense conversations about politics and their generational divide.

You can also catch Cumming on CBS’s new crime procedural Instinct, which follows a professor and author who’s pulled back into his former life as a CIA operative. It marks the first broadcast hour-long series featuring a gay leading character, and with that, another notch in Cumming’s belt.

After Louie opens in select theaters on March 30.

All that you’ve accomplished, both in and outside of acting, is really intimidating. Do you keep a mental checklist of the things you want to do or do you go with the wind, as it were?

I just do things that feels right to me at the time. That could mean working with someone I want to work with or a script I really respond to or the chance to go to certain places where I can buy some things. [Laughs] If I feel like I have enough money that I can do something I’m not gonna get paid much for—all those are considerations. Really, the common thing is, I go with my gut.

There’s a sort of comic scene early on in After Louie where Sam is talking to his agent or rep about the documentary he’s working on. He pointedly asks, “What? Too gay? Too political? Too AIDS-y?” What are your thoughts on the “gay film” or “gay cinema” labels?

I mean, I understand why. We all seem to say to someone, “Do you want to watch this film?” and they reply, “What’s it about?” It’s never, you know, “Do you want to experience a story?” I think we’re so used to the idea of saying, “It’s a mixture of Titantic-meets-Saving Private Ryan.” Everyone does that all the time now. We’re always pre-defining something rather than just letting people experience it. So I understand why it happens. It’s the same approach when I see books by certain novelists that are in the gay section. It’s the sort of thing that’s basically saying, “Other people won’t be interested in it.” I think that’s the danger. I hope that a gay storyline won’t be an issue. I hope that does not exclude non-gay people from being interested in it.

After Louie is largely autobiographical. You’re essentially playing Vincent [Gagliostro]. It’s one thing to portray a real person, especially if that person is alive to watch your performance. What is it like to be directed by the person you’re portraying?

Well, it didn’t really feel like that to me. I know that’s the case and I was aware of that at the time obviously, but Sam is a much more unlikeable person than Vincent. I mean, Vincent’s energy is very gentle. He cries a lot. [Laughs] He has a happiness. He’s a very sentimental and emotional kind of person. I think of Sam as a very closed-off person. So although I knew that Sam is Vincent and it’s autobiographical, I didn’t feel like I was being directed by that person. Vincent certainly never voiced that he wanted me to be like him. For me, the important thing was trying to just not be likable. I think that fucks with you because we’re so conditioned to try to be liked. Sam’s downfall is actually, in a way, his inability to do that.

You’ve certainly taken on serious material before. I remember watching Any Day Now, which is heartbreaking and super dark in places, but your character was loving and the sliver of light in that film. Sam is not outwardly charming, which is not something we normally associate with you, Alan. So are you relieved when a part like that is over or is it maybe more fun for you to play because it’s faraway from you?

It’s actually an interesting thing to play someone a little bit older than me and very different to me. I liked the fact that I had to do things I wouldn’t normally do in a role. I thought it was a nice challenge to switch off certain things that I normally have in my armor. Yeah, that was the best thing. I think that we’re all just so conditioned to—even if you’re a buddy, you want to be a charming buddy. It was just an interesting thing to not do that.

How far do you and Vincent go back, and for how long were there discussions about a possible movie being made together?

Let’s see—we shot the film in the summer of 2016. I would say we met a couple of years before that so in 2014 or maybe in 2013. I met him through Anthony Johnston, who’s the co-writer and also plays Braeden’s boyfriend. He was an old friend of mine. Anthony and I went to lunch one day and he told me about this movie he was asked to come on and help co-write. That’s how it came about, through Anthony. Then I became attached to the movie and met Zach [Booth]. It was kind of interesting because Anthony’s a younger guy brought into this story to represent the Braeden character and how Anthony and Vincent writing the script together mellowed the central story. Of course, it’s the younger one who brought me, the older actor, into the thing.

Zachary was telling me that there was some pushback on his part in regards to some of Vincent’s views on the younger generation’s seeming complacency and not entirely understanding what the AIDS crisis was like. Sam holds resentment towards Braeden in the film because of that. What are your feelings on that, Alan?

Well, I know people like him. I’ve heard those opinions. I don’t agree with them and I don’t have them myself. That’s not necessarily why I was interested in this film. When I first read the script, I saw this schism between generations of gay men. I knew people who expressed opinions from both sides, yet I had never seen something like this that actually made them engage with each other to voice the problem—the schism. You can play people that you don’t agree with. I don’t agree with a lot of what Sam says. But I also understand them. I understand his fears about heteronormativity. I think you just find your own way. Being closed off to experiences is not the way to deal with things. Life is about engaging and also about the compromise.

Having now gone through the Moonlight, and the Call Me By Your Name and the Love, Simon more recently, does it feel different bringing something like After Louie into the arena?

I don’t know… The fact that we’re opening in one cinema and on Video On Demand makes me think that things haven’t changed that much. [Laughs] I mean, this is not the same sort of languid film that Call Me By Your Name is. This is actually a bit more challenging and aggressive—that’s what it’s about. I think challenging and aggressive is still something that America is a little resistant to engage with, especially in a certain queer environment. I mean, we live in a world—and we live in a country—that encourages people to be afraid of others and ideas that they don’t understand. We still have a fight on our hands.

What are your feelings on some critics who point out that movies like Call Me By Your Name and Love, Simon are too sanitized for the purpose of engaging with mainstream audiences?

I can totally understand that opinion. I haven’t seen Love, Simon, but I saw Call Me By Your Name and enjoyed it. But also, you know, I feel that it’s just not dealing with the same issues that we’re dealing with. To me, [Call Me By Your Name] is this sort of fairytale almost—European vacation porn. I remember thinking, “God—they’re cycling down yet another beautiful road by a cornfield in the beaming sunlight.” So yeah, it’s a different thing than what After Louie is about. For me, I still feel that there’s something to be addressed in the way that queer people are represented and so I’m always very conscious of not sanitizing things. You do what you can. With the TV show that I’m doing, I’m playing a gay person in a same-sex marriage. It’s not very aggressive or challenging, but that in itself is what the big change is. You see a very stable and secure same-sex marriage and the fact that I’m showing that to millions of people who have never seen that before on television is to me making a big political point.

Oh yeah. Congratulations on Instinct.

Thank you.

The Guardian described your character as “a spy-author-professor-detective whose sexuality is both irrelevant and groundbreaking.” It’s irrelevant in that it’s a non-issue.

The depiction is me and it is part of the story. It’s not what the focus of the show is about and that to me is the breakthrough. Most often when people do this, especially on network television whenever there’s a gay character, the gayness is really what the whole story is about. With Instinct, it’s, “He does this, he does this, he does this, oh, and also, he’s gay and married to a man.” I think the very fact that it’s the fourth or fifth thing down the line about him is what’s important.

Mira Sorvino said as recently as this year that she would be totally down to do a Romy & Michele’s High School Reunion sequel. What are your thoughts on taking part as well?

Well, it was a great experience. It was my first film ever in America. It’s more that I’m aware how people are so passionate and devoted to this film. It’s lived on much longer and in a much fuller way than any of us anticipated. So it seems to me it’s ripe for a sequel. I would be up for it as well.

About a Boy: James Norton

About a Boy: James Norton Clarion Call: Garrett Hedlund

Clarion Call: Garrett Hedlund

No Comments