It sounds indulgent and risky to turn down a giant commercial so you can focus on your little art piece, but that little art piece could be the very thing that propels you miles.

Andrew Thomas Huang is the kind of person you hope to never meet in school. It’s not that they’re skewing the grading curve—not in your favor—obnoxiously personable or encouraging of whatever stupid project you’re working on. They already possess the kind of rare talent that far exceeds your own creative ambitions. The fear was very real: “When will this torment end?”

We met in 2007 when his short film Doll Face, about a CGI robot’s doomed struggle to conform with the media-frenzied hype for unattainable beauty, exploded on YouTube. It was a viral sensation at a time when such an exclamation was still in its infancy and sparingly used. Hollywood juggernaut J.J. Abrams came calling. Huang would go onto direct a string of commercials and music videos for high-profile clients like Lexus and Sigur Rós. Naturally, another short Solipsist came along, which was selected for the Saatchi & Saatchi New Directors Showcase—previously a launchpad for Spike Jonze and Michel Gondry. Then some Icelandic lady named Björk called and asked the 29-year-old to do something awesome for her next video.

Huang just recently premiered the new video for Atoms for Peace (the Thom Yorke-fronted supergroup) at the Hollywood Bowl to a crowd of 10,000 people. If you don’t know the director by name, you’ve surely seen his work. Here’s our talk about everything from Björk to Terry Gilliam…

Are people usually surprised to learn that you majored in the fine arts?

A lot of people do assume that I studied film. Although I was near the film program, I always worried that if I studied it I would end up getting people coffee. I felt like as an artist, I had a specific trade that I could offer. I’m sure you felt the same way too. People still ask me if I want to get into features.

Do you?

My short answer is yes, definitely. At the same time, I’m a bit more excited to exist more as a video artist even though the practical side of me says, I won’t have any means to support myself! [Laughs] Some of the artists that I admire most are, obviously Chris Cunningham, and Daniel Askill. I look up to directors who have a strong sense of what they want to make, but are also commercially viable. I do want to eventually make a feature and have some ideas outlined, but I watched other people go through the politics of making one and it freaks me out. I think I might be more interested in the critical discourse about moving images. I think I’d be as equally excited to have my work shown in galleries as opposed to theaters. Projecting work on a wall in a gallery is a little closer to me, not to mention more doable at this point in my trajectory. Having said all that, I would be really disappointed in myself if I didn’t get a feature made at some point. Movies are still so much of what I think about when I make anything.

You have plenty of time left to think about this, Andy, and you’ve been doing installations all this time anyway.

To be honest, I haven’t done a lot of installation work since college. Although, I was a creative director on a holographic fashion show recently for New York Fashion Week. Radical Friend directed that. Essentially, I guess you could call it part installation and part catwalk… part opera. [Laughs] It featured a collection by Giles Deacon, a British designer. It was kind of nice to dabble in something new that wasn’t a film, but treat like a film as a live event. I’m excited to do more experiential work.

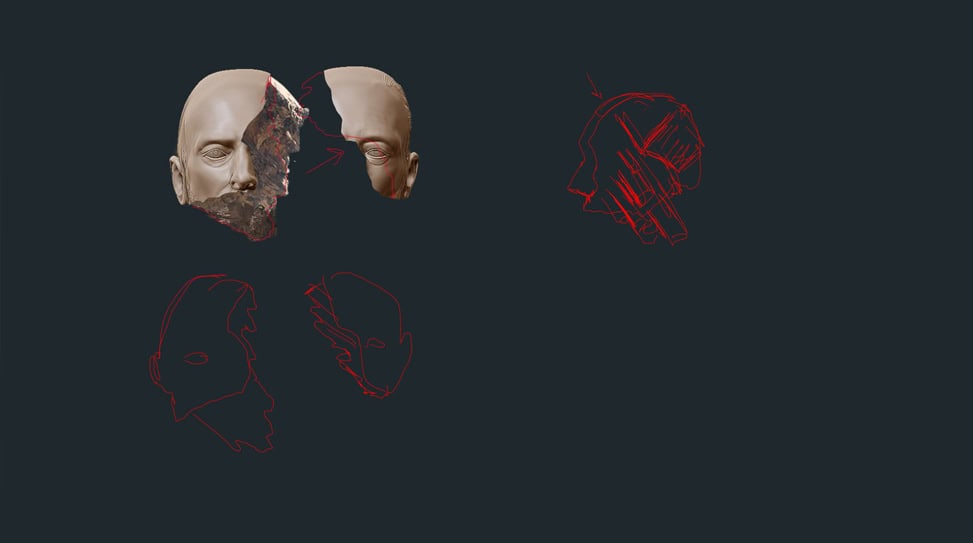

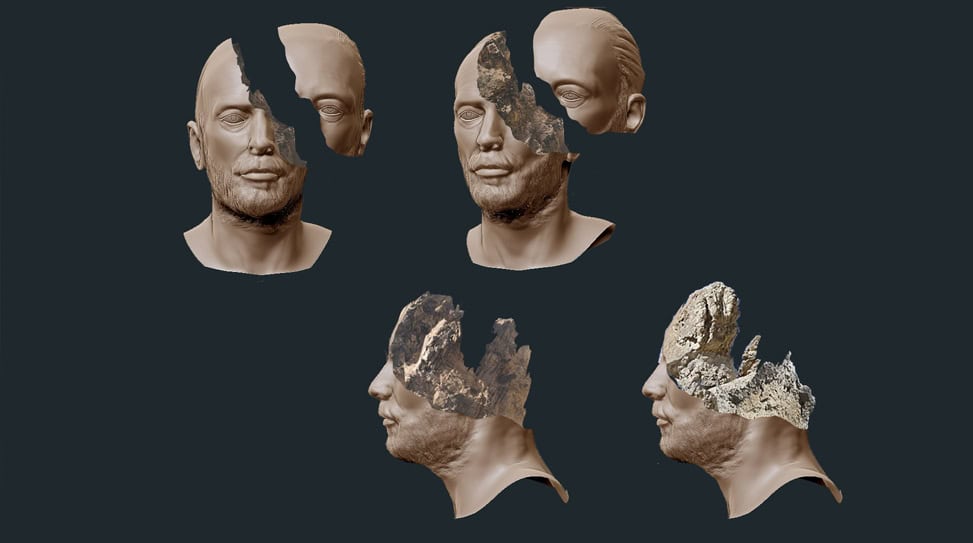

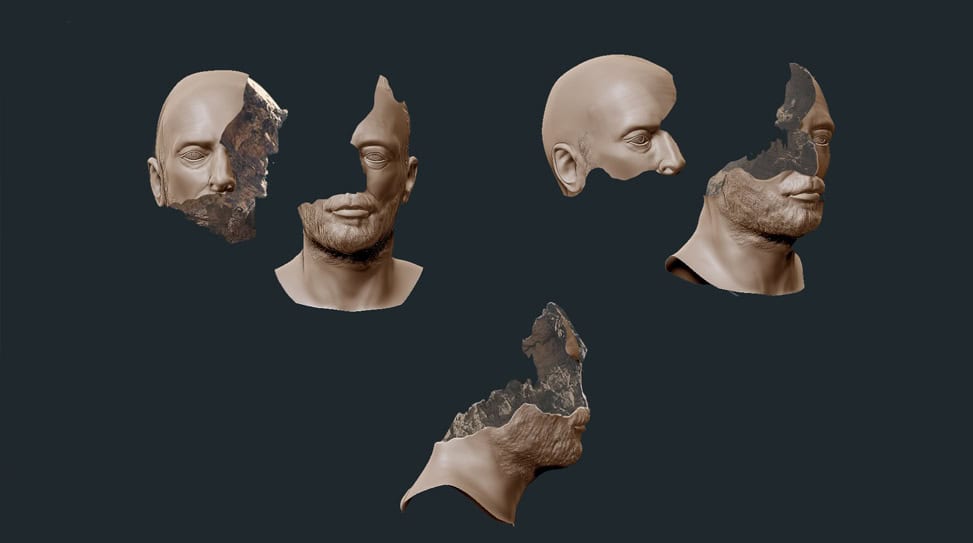

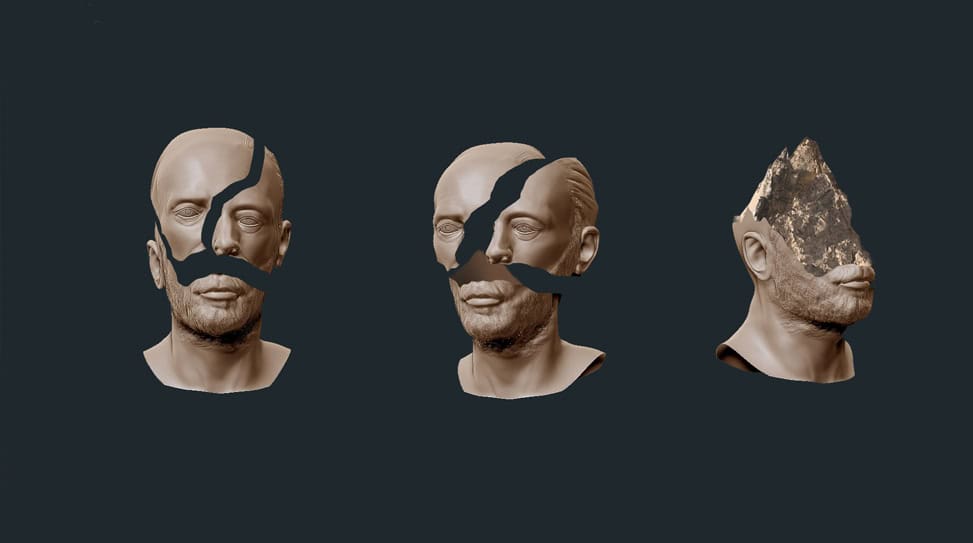

What’s happening with your Facial Alphabetics installation that I’ve been reading about?

I had that slated right before Björk happened, so it got shelved. I didn’t give it up though because I think it shows a new trajectory that I want to move into. For a while now, I’ve wanted to make something darker and more minimalist.

If I bring up irrelevant topics for the remainder of this talk, feel free to ignore them.

It’s totally cool. With the Internet, we post stuff or semi-post stuff and elude to stuff, but things change and your career changes. You just can’t get to it. I fail, on my part, to do any important clean up to make sure everything is up to date online.

Some things you can’t even delete yourself because it’s up on some random blog.

Exactly. I can’t delete Doll Face. I’m so embarrassed by that now because I was in a different place as a person and the Internet was in a different place as well. At the same time, it afforded me everything that’s happened, so I’m grateful. I guess the most important thing that I’ve learned since directing is that you can restart your career. You might not be able to do it more than a couple times in your career, but in your 20s, you have a solid set of years after college to experiment and make mistakes. I’m realizing that as I approach my 30s.

Was Solipsist the start of a new beginning for you?

Completely. After releasing Solipsist in 2012, I felt a lot of new opportunities coming my way. Since graduating USC, I had done a lot of commercials and random videos, some of which I was sort of proud of and a lot of others which I wasn’t so proud of. Making a short film had given me career momentum, but that soon faded.

You’re of course referring to Doll Face, the surprise call from J.J. Abrams…

Yeah. That was just another time. It was painful to go through that, but it was also a good learning experience to see something do well on the Internet that opened all these doors. But those doors close just as quickly. People just move onto the next best thing and new directors come into trend every year. In 2011, I realized I had to scrap everything from my reel and make something challenging that I hadn’t done before. It totally refreshed my palette and I approached my career with longevity in mind. Longevity is what’s on my mind most these days because there’s so much content out there.

Now that you’re signed to reputable companies, do you feel like you don’t have to hustle as much on your own?

Signing with Blinkink and Colonel Blimp in London, and LEGS in New York just amplified everything. I wouldn’t say that massive brands are knocking on my door because, truthfully, the traditional directing path of doing commercials and music videos is still relevant. There’s a natural, step-by-step process that you go through. Clients want to see that you’ve already done the kind of work they’re looking for. I’ve actually hidden a lot of my past commercial work from my reel. I’m getting a lot of interesting creative projects, which is what I want, but they’re not necessarily the highest paying jobs or for the biggest brands. I do feel an upward momentum though.

What do you think is the most viable thing in bridging this gap between what you’ve done and where you want to go next?

I’m really thrilled to have worked with Thom Yorke and Björk, but now I want to prove that I can do something else. No one will give me that opportunity unless I prove to them that I can do it. Usually, no one will just hand you that opportunity and I have to carve it out for yourself. Steering your own path always takes a degree of investment whether it’s financial or time spent doing something no one thought you could do. Maybe you do that and fail, so you try this a couple of times. I think the concept of investment is something that we’re not always taught in school. You have to seize what you want sometimes. The gap is always there and it’s not easy.

Your work always seemed elaborate to me and I know you were practically doing everything yourself. How have things changed now that you have teams of people dividing up the labor?

It’s funny because I’ve worked with larger crews on commercials and you have a safety blank there. Commercials are typically well-funded and no one’s starving to work, which makes it easier to delegate. When it comes to a passion project, you have to get really creative, not only in terms of financing it, but taking care of the people donating their time. With Björk, it was admittedly more chaotic because I was directing and producing the post-production side of things myself. Simply, hiring, looking at reels, writing checks and trying to remain creative, while compositing and animating a lot of it myself was completely insane. I knew I couldn’t do something like that again.

How similar or different was the experience with Sigur Rós?

The Sigur Rós video came just after Björk, a very fly by the seat of my pants experience. There was such a contrast. Since Sigur Rós was so live-action heavy, I was able to do a lot of things on my own. Yet, it was an 8-minute song. It was my first time working on a really big project, but it was strange how isolating it was. I was the one person in the studio spending the most time working on it. I did this with the help of The Mill in Los Angeles and they were crucial in providing help with rotoscoping and color correction, not to mention giving me another roof to live under. It was also a window into how efficiently they run over there.

When Sigur Rós came to me, I was so massively delirious from working on the Björk video. I remember thinking: I need rest. Now. I need to sleep… but I want this. [Laughs] They always say, you want your next opportunity lined up. I’m glad I did it, but I felt like my vision wasn’t as clear on Sigur Rós as it was on Björk. I was also very cognisant to the fact that they are two of Iceland’s biggest exports. It was imperative that I didn’t make the videos look similar to each other. The “Brennistein” track was such a massive departure from their previous work too, as a result of the band losing their fourth member. It was so much darker and just so agro.

What did the original treatment look like?

The original idea was quite narrative. It was about a group of people arriving on an island in order to transform—like how snakes shed skin—by migrating across the planet to mate or lay their eggs. I imagined these three people arriving on an island to perform some sort of exorcism or exorcise these demons out of themselves. I think the band and their manager thought it was too explicit and intentionally wanted something more abstract. The first time I pitched the idea, I told them this story. The second time I pitched, I treated it more like an art piece and talked more about procedure as opposed to narrative—the narrative was still there, but I presented it like, I’m going to create three different set-ups that involve the act of exorcism. One would involve the actual performers. One would be completely abstract using sculpture. The third would involve sulfur… I forget exactly what I said, but when you think about sulfur, something purging and erupting into the air comes to mind. It was like one narrative being told three different ways, a movie with three acts.

We seldom hear from bands what they think about their video unless they publicly trash it. How did Sigur Rós react?

They told me they were happy and I believe them. But it was quite difficult getting there. They focus on their music. They were so focused on recording when we met up to shoot this. It was hard to get them to articulate what the track was about. I think every artist is a vessel and they’re channeling something greater than themselves before spitting it out. I don’t think you can expect every artist to talk about it. I even asked Thom Yorke what his song was about and he was very reluctant to put a finger on anything. I think he could’ve told me if he wanted to, but he didn’t feel comfortable divulging. It’s kind of like asking a kid, “What’d ya paint there?” I don’t know. It’s a, it’s a… clown. [Laughs] No one wants to talk about what they pooped out.

As long as they’re happy with it, right?

All in all, I don’t think the band was as verbal as some of my other collaborators. I do think they wanted something a little cleaner. I think they were worried that it would be really grungy, which it totally ended up being for a multiple reasons. [Laughs] One thing they wanted was for it to look modern. I think I get that now, but I don’t think I quite got it then. I think they were worried that it would look like The Wicker Man or too pagan. I didn’t know if they wanted us to add something really contemporary like a pair Nikes. It took a lot of decoding, which is totally fine. For me, on a totally personal level, I need textures so I tried to address their notes that way. For example, we used a lot of VHS tape.

I doubt VHS tape will ever look as cinematic as it does in this video.

I wanted to choose that material because it’s black and shiny. Again, in contrast to Björk, which was very matte and powdery, I wanted Sigur Rós to be shiny and wet. So they said they were happy with it in the end, but you never know sometimes. Maybe they’re just polite.

On this new Atoms for Peace video, was it a constant back and forth between you and Thom Yorke during the preliminary stages?

The creative talks between us happened in May and June. After doing the Sigur Rós video, the commissioner at XL reached out to me with this new track and Thom apparently liked my work, so we met up in L.A. I was thinking he wanted to do another dance video because he did those videos with director Garth Jennings. He specifically mentioned Solipsist and how he wanted a similar hypnotic, psychedelic rippling quality. He said the song was very much about Los Angeles and moving through a landscape in high-speed. That’s when I knew this would have to be a completely manufactured world. I developed the treatment about five times with him and he really worked with me to narrow it down. I feel like a lot of his work has to do with unsustainability and there’s always an apocalyptic, prophetic urgency to his work. Even the artwork of his album features all these buildings in Los Angeles and things being swept away, fire raining down. It’s quite biblical. It brought to mind this poem that I read as a kid called “Ozymandias” by Percy Bysshe Shelley, an English poet. I just remember it very distinctly because the poem was written from the point of view of this collapsed statue of a king of an ancient civilization. He talks about how great his empire is, but really, he’s just this collapsed statue in the middle of a desert. That kind of became the idea and Thom brought up Jason and the Argonauts, the Ray Harryhausen film. Have you seen that movie?

I haven’t, but it sounds familiar.

It’s really old stop motion stuff. We’re venturing into B-rated, science fiction here. He wanted there to be a hokey quality, a cheesiness about it as well. This combination of an apocalyptic narrative and wanting there to be a hypnotic quality became the main focus. So we nailed that down before production and shot it in L.A. in June before coming to London at the end of June where we continued to develop the look with the artists here.

Using Thom as an example, would you say it helps if the artist brings a lot of specific ideas to the table be it visual cues or a really solid concept?

Absolutely. To me, that’s what makes this whole process worth it, to feel like you’re collaborating and not just giving them something on a platter. The dream scenario is if they’re actually participating or if they have carefully chosen you and give complete trust. Björk and Thom Yorke have worked with so many different artists over their careers and I know it isn’t easy for them to choose collaborators. I feel really lucky to have worked with them. They obviously know what it means to collaborate, so they gave me enough space to be able to do what I do. I was actually supposed to deliver this video a long time ago, but Thom thought, “Well, we need to do it right.” That kind of empathy is not to be taken for granted.

What are you excited about exploring next in terms of the bigger picture?

After this Atoms for Peace video, I’m determined to do something completely different. I know it will still very much be me, but I really don’t want to do anything that involves rocks, sand or psychedelic colors. [Laughs]

Is that a gamble since clients most often hire directors based on their previous work just to have them repeat something?

No, it’s true. It’s a balancing act. You have to have a brand and a style that’s specific enough that people recognize your work. You have to fall into some kind of category in order to become a business and market yourself. Tim Burton is probably a great example of this. When you look at something of his, you know it’s Tim Burton. But in terms of his recent work, I think we can all agree that he hasn’t been as risk-taking. You can have a trademark, but you also need a set of rules for yourself in order to break them, and still remain you. It’s quite a paradox to follow in order to have a successful career. It’s not easy.

You know what Tim Burton should stop doing? Casting that Helena Bonham Carter in goddamned everything.

[Laughs] I think Tim Burton has a very specific kind of babe. He definitely has a type.

I completely derailed this conversation. Looking over your body of work, what are some recurring themes or motifs that you see?

I guess some themes that I maybe subconsciously always incorporate has to do with body-identity, the idea of things crumbling or disintegrating, sublime transitions from one state to another, hypnotic loops, labyrinths… I’m just spouting out these words, so they’re not entirely accurate. If you look at the work of Terry Gilliam, who’s one of my great idols, Brazil is so different from The Holy Grail stylistically, but his humor and stories always remain the same. His stories are always about escape, the absurdity of bureaucracy and disillusionment with modernity. The point is, no matter what style he chooses to work with, it will still be him because of his ideas.

When you work on personal things like Solipsist, how do you find the time? Is it as easy as turning down work and going off on your own tangent?

You need to do two things: You have to save up enough money so you can survive while working on the personal project and you also need to say no to a lot of people. I would say Björk and all the other videos that I’ve made were personal passion projects, but to make something that’s completely mine is important because you have no one else to answer to. It sounds indulgent and risky to turn down a giant commercial so you can focus on your little art piece, but that little art piece could be the very thing that propels you miles. When you say no, you’re also worried about tarnishing relationships. When you say no to a client, you’re sending a message to them. Sometimes that message is rather alluring.

They will remember that.

Exactly. It might make them want you more if you’re lucky, but maybe they’re thinking, “You’re lucky we even considered you.”

What’s something significant that you’ve learned so far in your career that you find really meaningful?

I read this book called Art and Fear once that gave really concrete advice. There are different levels of urgency when it comes to your work. There’s the most urgent work and the least urgent work, but you also have the most important work and the least important work. Oftentimes, the most urgent work is the least important. Other times, the most important work is the least urgent. I’m not saying I’m good at mastering this. [Laughs] If you dedicate at least 30 minutes a day to the least urgent, but most important work, you’ll get somewhere. This is going to sound really dramatic and cheesy, but I think in our careers, 9 out of 10 moments will involve something that we don’t want to do, something that we think is futile or tangential to our real goal. I remember pitching on this commercial for colon medication: “Did you know that your colon is 12 feet long?” I remember that moment and being so down. [Laughs] I couldn’t believe that.

Vital Stats: Allan Rayman

Vital Stats: Allan Rayman American Spirit: Henry Grace

American Spirit: Henry Grace

2 Comments