Surrendering to all the rejections in your life might lead to something positive.

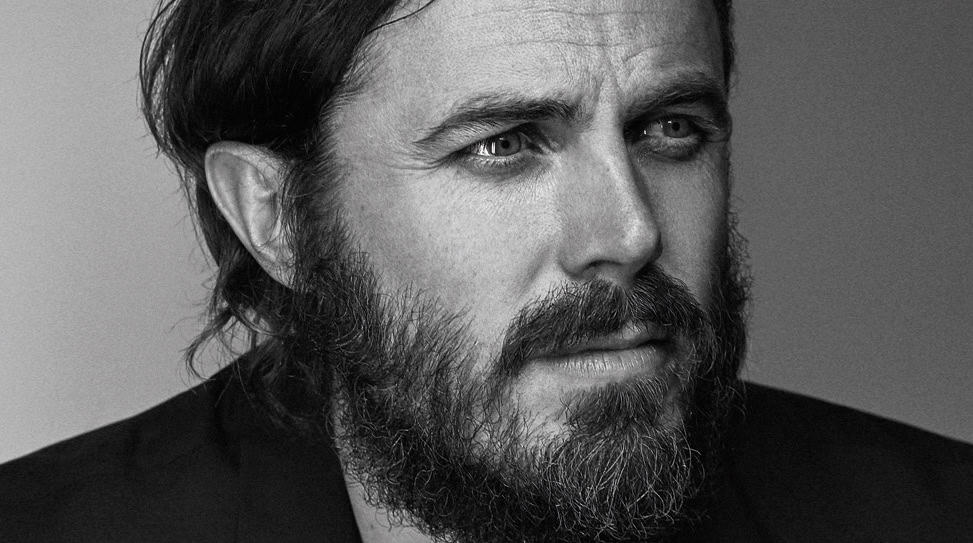

Light of My Life marks Casey Affleck’s narrative feature debut as writer and director, after 2010’s I’m Still Here, a quasi-documentary that charted the (apparent) public breakdown of his former brother-in-law Joaquin Phoenix. An artisanal entry in the crowded post-apocalyptic survival subgenre, the slow-burn two-hander is decidedly minimalist and sincere in its nature, and sees Affleck cast himself in the role of a protective father, and by extension, the guardian of our future.

It all begins with a bedtime story. The film’s unnamed Dad (Affleck) spins a rather fractured and rambling variation on the Noah’s Ark parable to his pre-pubescent daughter nicknamed Rag (newcomer Anna Pniowsky). Only gradually do we realize that they are dozing off to sleep in a crammed tent pitched deep inside a foggy and dense forest, hiding out from a threatening world.

Our protagonists are caught in a pandemic that’s responsible for the wipeout out of half the world’s female population. This includes Mom (Elisabeth Moss), who fell victim to the “female plague” shortly after Rag was born. In Mom’s absence, the pair have remained off-the-grid and left foraging for food, rarely going into town for provisions. Dad fears the news of a daughter will bring deviant men hunting for them both. So Rag’s under constant disguise—consider her short and thatchy haircut, that of a boy. Roaming the foliage to abandoned farmhouses and back into the wilderness, the paranoia and the rootlessness of their peripatetic existence is wearing them down.

It’s tough to say what’s more surprising here: the fact that the first narrative feature Affleck has produced concerns a world in which women have been almost eradicated—the film can partly be read as a creative apology following his accusations of sexual misconduct, for which he has denied wrongdoing—or the fact that he handles the topic with such loving care. Surely, Light of My Life has less to do with the pratfalls of a male-dominated society than the psychological duress of a parent struggling to raise a kid on their own. Affleck says so himself: “It’s clear I was writing about raising a kid after divorce. Mom was gone, so in movie language that means all moms are gone.”

Regardless of Affleck’s motivations or intentions, Light of My Life is a superb film crafted with an abundance of sophistication and depth of feeling. It’s also further proof (if more was needed) of his exceptional gift as an actor, especially playing dazed introverts adrift in empty worlds—Kenneth Lonergan’s Manchester by the Sea, for which he picked up the Best Actor Oscar in 2016, was but one indication—and there has been no empty world quite like this one in his expansive oeuvre.

Affleck’s next feature as writer-director is Far Bright Star, which will reunite him with Phoenix.

Light of My Life opens in select theaters, and hits Digital and On Demand, on August 9.

You’re not only one of our gifted actors. You’re supremely well-versed behind the camera.

Aw. That’s very nice of you to say. Thank you, sir.

You began writing this story a decade ago. It came from a deeply personal space.

Yeah, for sure. I’m not a good enough or well enough trained writer to know how to write anything other than what’s happening in my life—not yet anyway. If someone asked me to invent some story set on another planet or to write a movie based on one of the stories from the Bible or something, I wouldn’t be able to do it very well. This was something that came out of conversations that I had with my wife and I just cobbled them all together into a movie.

Did you fulfill what you set out to do? Did the film help you to process the questions, thoughts or anxieties you might’ve had about raising your children as a single parent?

That’s a really good question. It definitely helped me to understand better a lot of the things that I was thinking about when I was writing it. The writing process and then the shooting was a way of exploring the things I was trying to say—the things that were on my mind a lot when I sat down to write them. Do you know what I mean?

Of course.

It was definitely a way of working through some of those moments that fly by unprocessed in a day of just trying to keep up with all the things that you’re doing. It’s why I feel so lucky to be able to be in this business and just to tell stories for a living. I can’t think of a better profession for myself. I mean, I have a few ideas, but it really does help to understand the things that are sometimes trapped inside of you that you don’t understand.

I guess it was surprising to learn that you had initially started writing about a dad and his two boys before your real sons rejected that idea, if only because the story and the world you concocted is so heavily centered around Rag being a girl. The resulting film is maybe not too different at its core, but it would’ve changed the narrative, don’t you think?

I think the directing would’ve been different. But really, the feeling of it would’ve been exactly the same I have to say. I’m glad that [my sons] had that response. I’m glad that they were able to tell me that and didn’t feel like they were at the mercy of someone who’s just gonna write about them and embarrass them. I’m glad that they were able to say, “Don’t write or make a movie about us.” And I’m proud I was able to respect that. I think it worked out for the best for whatever reason. It just seemed to work. I found Anna [Panikowsky] and that was great. Things kind of fell into place. So it’s another example of why their rejection of my initial idea was a good thing to surrender to. Surrendering to all the rejections in your life might lead to something positive.

Watching the very first moments of the film with Dad’s bedtime story, I got to thinking about how significant that chapter is in our lives. Storytelling is so intrinsic to our development. It’s the very first time that we’re a totally captive audience to our parents and imagination. I wonder if that was inspired by your own childhood.

I don’t think anybody ever told me stories when I was a kid. I don’t remember my mom and dad ever telling me a single bedtime story. My mom told me that I would cry when I was going to sleep so they would turn the vacuum cleaner on in my room to drown it out. Those were the old days, boy. Growing up, I don’t remember anybody doing that. I guess as you grow older it would be strange if they told you bedtime stories for some reason, but I don’t remember ever getting any stories like that. It has certainly been fun to tell to my kids, to make up and for them to hear them. And I think you’re right, it is a very important and precious developmental stage, that age when you hear those stories and really believe in those stories. Also, there’s one point in the [bedtime story] where Rag asks if something really happened. It reveals that, at the age she’s at and the stage of life that she’s at where she’s hearing this bedtime story, she understands that it’s just a bedtime story about animals talking to each other and taking a boat. All this really far-flung stuff. But she’s still engaging with it, even though the line is very blurry for her still. She wants to know if this thing didn’t happen like that, that couldn’t have happened like this. Critic is too strong a word, but there’s a part of her that wants the story that’s full of very colorful, fictional invention to reflect reality, to want these talking animals making their own boat to behave like things that resemble something like reality. I thought that was kind of a funny point in a kid’s development.

There’s a moment of nuance in the film, a small detail among many, that really struck me. It’s where Dad and Rag are walking over the bridge and she suddenly changes her gait with marching arms to appear more like a boy. There’s no exposition and it’s so effective in communicating that idea. How do you play around with stuff like that as a director on set?

That’s funny, man. There’s very little stuff that happened spontaneously I guess—well, that’s not true. There’s a lot of little performance stuff that happened spontaneously, obviously. There were very few script changes. That was one where we were just walking over a bridge because there was a bridge there and I wanted to show a memorable transition from the woods towards the town. When they’re going back from the town into the woods, that’s something you can remember as a transitional point. Also, in the movie it’s a lot about stories and arch good guys and bad guys. There’s always a crossing of the threshold in myths and mythology. There’s always that point where your characters either enter or leave the woods and cross some very clear threshold. The bridge became that, not that anyone is thinking that when they’re watching the movie. So that’s why that was there. Then I just thought it’s really boring if [Rag] is really mad at me. Why don’t we just have her make fun of me behind my back? Then you start to see that she has all of this personality all on her own, you know? Siblings will sometimes make fun of their parents together. They’ll rebel together. So in one moment you see how alone she is. You see that she’s starting to come of age where she can be mad at her dad and make fun of him. I’m walking a certain way and she makes fun of it. In my mind, she wasn’t practicing walking right like other than she was—she was mimicking me because it was fun to her and she was mad at me.

You write about the things you love. In this case, they are post-apocalyptic movies, the woods, and realism. So much of the realism for me came through in the dialogue. Even for someone like myself who’s not a parent can appreciate how Dad communicates with his child. He doesn’t shortchange her, even though he’s obviously protective of her in a way that fathers should be. He just seems to know what to say all the time. Did the writing come naturally to you, maybe having had very similar experiences of being a parent? I’m totally convinced that you’re a really great dad from watching this.

I think in the way that sometimes when you’re in an argument with someone and you go home or in some charged situation and you go home and you think I shouldn’t have said this or I shouldn’t have said that. The script is sort of like me thinking I’m going to shoot an actor like this or like that in some instances. It’s those conversations I’m sure that I had with my kids where I didn’t do quite as well, and that’s not to say that my character doesn’t make a lot of mistakes in how he handles situations. But a lot of it is me sitting down at the computer thinking, “What if he said this?” So I guess in some ways I’m a little bit like the character in the movie. But also in real life, I cave a lot more than my character does. They kind of walk all over me.

You have such a dense filmography that it would be futile to broach that subject in any meaningful way here. But I do want to ask you about the culmination of experiences and learning that comes with the territory of any craft. In speaking about Light of My Life specifically, I wonder if you can look at your own work and know, “That’s something I picked up from that director,” or “I remember them directing me like that on a movie and how much that helped me, so I’ll use it”? Of course, it’s coming in like osmosis I can imagine and it’s not so calculated when we talk about the things that inspire us.

I can try to identify a few things. You said it well, that all of that learning happens by osmosis and spending 25 years on sets and being around directors, there’s a lot of things that I’ve learned from them that I don’t know that I’ve learned. I can say with some confidence that there’s nothing that I’ve learned—nothing that I am as a director—that I haven’t learned from somebody else in my career. I didn’t go to film school. I didn’t grow up to be a director like Steven Spielberg making home movies at 7 years old. It was really just a result of being on sets a lot watching movies get made, admiring those directors, being impressed by what they were able to do, copying them, and slowly learning and having my own version of what they were doing. I would say that I have learned a lot from Gus Van Sant. I’ve done four movies with him—one as one of the editors, or the assistant editor, really. He’s a very open book and very inclusive, collaborative person. He was the first person that I’d worked with and he treated everyone like an equal. He would want to hear ideas from everybody. It was great to watch him work and I got to watch him work on To Die For and Good Will Hunting and Gerry and Finding Forrester. Also, even with David Lowery, who’s younger than I am, but I learned a ton from him. He’s very talented and has his own way of doing things. And Andrew Dominik who’s someone who’s one of these—I mean, he has no business of knowing as much as he knows about acting. He has never been an actor. He has never taken an acting class. He had made one movie when I worked with him [on The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward]. His notes and direction are just brilliant and I think he made every single actor on that set better. He was working with incredibly talented, experienced people: Sam Shepard, Sam Rockwell, Brad Pitt, Mary Louise Parker, on and on. So there are some people who just come to the job with an innate understanding of all aspects of moviemaking and then there are some people who just have to sort of cobble their skills together along the way like I’ve had to do. I’ve done it through observing and feeling from all those directors I’ve worked with.

You recently told Deadline: “Being original is not saying something nobody else had said—it is saying exactly the thing you wanted to say.” I think that’s really key. What else have you learned about filmmaking, or about acting, that you find to be really true and helpful to you to remember time and time again?

From the beginning of time, we’ve all enjoyed stories and there’s been some real evidence of that. We’ve developed who we are as human beings through storytelling. That is why we have movies in the first place, or plays. That’s why we have actors. So stories are connected to our own understanding. It’s the way we make sense of our own identities and the world. For thousands and thousands of years, those stories were not told for the purposes of making money. They were just told to entertain or to teach lessons, like little morality tales or sitting around the fire talking about the kid who strayed too far from the village and got eaten by a lion. Those stories are told from a place of concern or to teach or love or to amuse and they’re usually for that reason very personal stories. Therefore, telling personal stories, no matter how big or how small or how much you think no one will connect to them, are usually the stories that find an audience. They ring true to people. They feel like they help people relate and excite that primordial little thing inside that was the whole reason that humans liked stories in the first place. In the spirit of that, Light of My Life defies anyone’s idea of what you want to make if you want to get people to go to the movie theater: mainly, don’t tell a story that’s basically two people set in a tent. But then it still hopes to connect with people because, even though it isn’t technically in any aspect a commercial movie, it is something that was personal and something that I think everyone making it cared a lot about.

About a Boy: James Norton

About a Boy: James Norton Clarion Call: Garrett Hedlund

Clarion Call: Garrett Hedlund

No Comments