If you’re not sacrificing a little bit of yourself when you’re acting, I don’t know if you’re really giving the audience what they deserve.

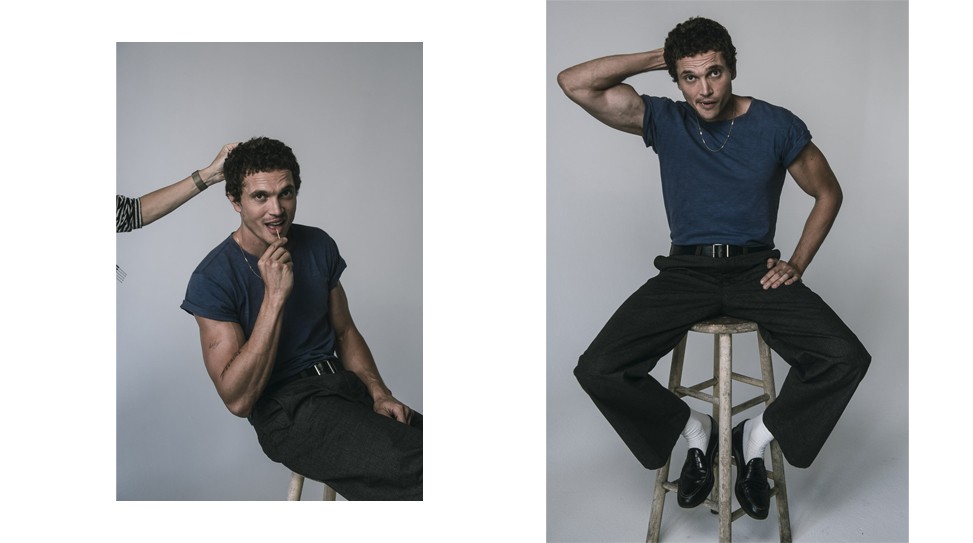

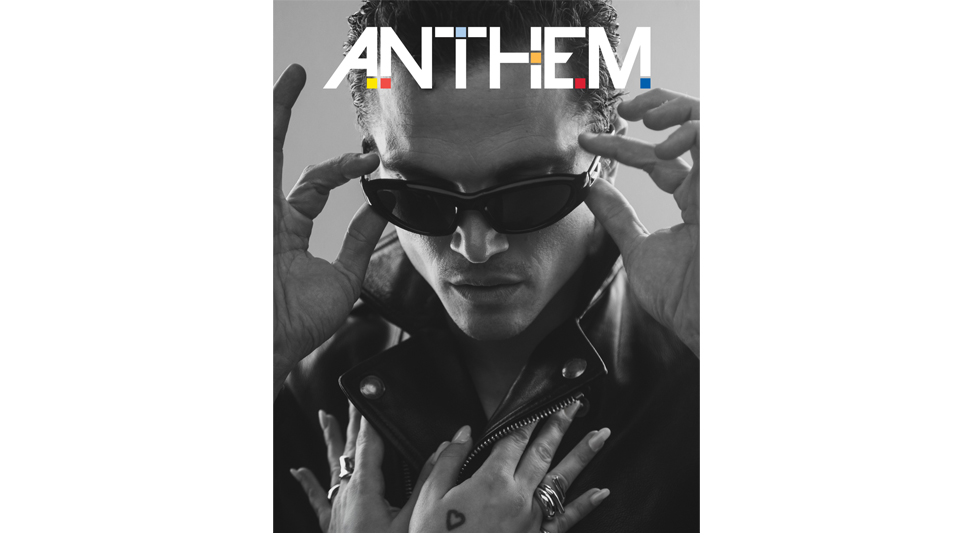

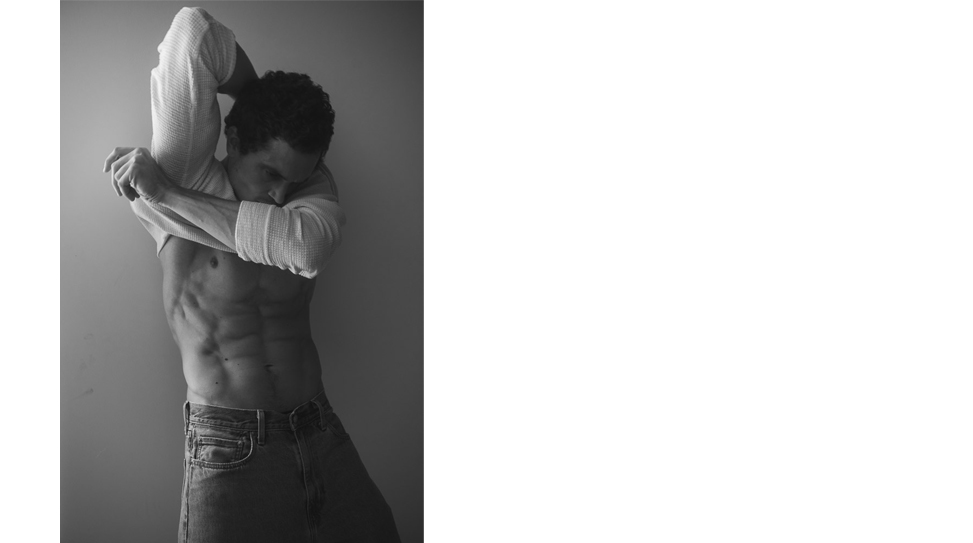

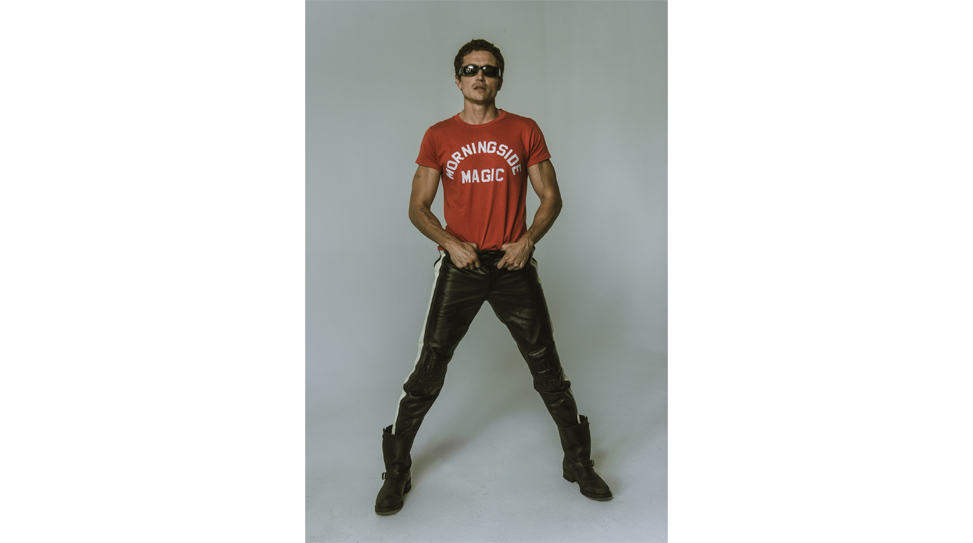

Photography by Reto Sterchi

Styling by Sandra Amador

Styling Assistant: Christina Corso

Grooming by Kimberly Bragalone

Produced by Jesse Simon

Location: MVMT Studios

Global Brand Ambassador: Kee Chang

Look no further than Gaspar Noé’s Love. When the provocateur world premiered his sexually explicit 3D opus at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, the reception was exactly what you’d expect—it was loud, divisive, and impossible to ignore. And for Karl Glusman, it became his calling card. Then a fresh face charged with going full-frontal in his audacious debut, the actor was on the precipice of more incredible opportunities to come, notable among them Nicolas Winding Refn’s The Neon Demon, Tom Ford’s Nocturnal Animals, Jeff Nichols’ The Bikeriders, and Alex Garland’s Civil War. Call it what you’d like. Talent. Hard work. Being in the right place at the right time. A matter of good taste. Ultimately, they all work in concert. And fortune favors the brave.

Most recently, Glusman flaunted his comedic chops playing a chronic screw-up with more charm than reliability in Shawn Simmons’ heist-cum-love story Eenie Meanie. Next, he will star opposite Glen Powell in Edgar Wright’s The Running Man—a new adaptation of Stephen King’s cult novel.

Anthem recently connected with Glusman for an in-depth conversation, and a photoshoot in LA.

The Running Man opens everywhere on November 7.

Hi, Karl. How are you doing, sir?

I’m doing very well!

How is Los Angeles?

Man, it’s weird… So, I ride a motorbike around town. That’s really my happy place, cruising around on the east side. But I don’t know… The news stresses me out. The environment. The government. The deportations. People are both wonderful and strangely desperate in this town. I have a funny relationship with it. I love this place. At the same time, sometimes, I wanna run away.

The world’s upside down, unfortunately. You know, I’ve been very curious to speak with you.

Hopefully, I can live up to it. [laughs]

I’ve been aware of your work, of course, but then I’ll also be watching Civil War with our mutual friend and he’ll be texting you in my periphery. So I knew this was coming down the pike. And Civil War is a point of interest because it’s one of my favorites from last year. Do you think that film is pretty indicative of the kinds of projects you like to be a part of?

Yes, and it’s twofold. Firstly, Civil War is this rollercoaster of a ride with entertainment value. But it also forces audiences to ask difficult and very important questions. What are we headed towards? How do we lose our humanity? How do we relate to one another? It’s a movie that invites discussions, which is the kinds of projects I wanna be a part of. It’s also with a filmmaker—an auteur—who I am crazy about. I’m a huge admirer of Alex Garland. And the fact that I’d worked with him once before and was invited back, as a private contractor, it’s the best compliment I could receive. Anytime you get asked back, it’s like, “Okay. I did a good job.”

Whenever actors have repeat collaborators, whether that’s with directors or even fellow performers, that tells you everything you need to know. Putting it simply, you’re wanted.

Because you get together for a month, two months, six months—however long it takes. You do that and the movie exists. But as you’re doing it, there’s also the life around the movie, you know? There’s a community that you can build. Alex does that, which means he often brings the same people back. It feels like a troupe. That environment is lovely to be in, if you’re so lucky.

You’ve worked with your share of distinctive voices in cinema, like Alex. Gaspar Noé. Nicolas Winding Refn. And you once admitted that you distrust feeling too comfortable in acting where things come easy to you. I wonder if that might be your perfect storm: working with a visionary filmmaker, and knowing that it will present big challenges along the way.

Every director has their own way of working, right? So it’s hard. It’s difficult to go in and expect the same experience every time. I think of directors as dance partners, and everyone has their own way of dancing. I’m very curious to learn how people work and how they think. The thing is, movie sets are rarely ideal. There’s always a lot of distractions. You’re always fighting for time and weather. There are budgetary issues. So your concentration is really important. I think the perfect storm is being on a set where, even if the director is not by your side coddling and coaching you through every moment, they trust you. They have your back. Trust really is the biggest thing because then you feel like you can take chances. I can fail. If you can find yourself in that place where a filmmaker allows you to do your job while still serving their story, if they allow you the room to try and find that little moment that’s so hard to find, you can also find a flow state, basically. Then you’re not second guessing yourself every step of the way. You’re trusting your instincts, and they’re encouraging that. You end up being much less cerebral. It’s like jazz, I guess. You’re playing jazz and you’re flowing. When you’re with the right filmmaker and the right group of people to facilitate that space, it can be really fun. But at the end of the day, you’re going to work. If you can’t find that promised land, it’s up to you to still give ‘em the goods.

Right. It’s a job, too.

I’m not knocking him when I say this ‘cause, again, everyone has a different way of dancing: I shot one day on Paul Schrader’s new movie [The Basics of Philosophy], and he doesn’t like to talk. He doesn’t have time for that—he’s running out of years left in his life. So I had to make myself feel good about what I was doing. He wasn’t gonna come up and say, “Great job.”

I suppose trust goes a long way, especially in a tricky situation like that where the communication is lacking. And trust goes both ways. When does that normally come into play for you? Is trust something to find in the trenches, or do you need it from the get-go?

Personally, I think I need it in the beginning. I want to know. I want it. Maybe I’m a bit needy.

I don’t know if you are, but that’s certainly honest.

You’re not gonna become friends with everyone you work with. But for me, if I’m friendly with the person that is telling me what to do, I will go to the ends of the earth for that person. If I feel like that person thinks I’m dumb or don’t have value—if they don’t see what I can bring to the work environment—it’s easy for me to shut down and see them as the enemy. And that’s silly because, ideally, we’re all there to do the same thing: make something worthwhile. Ego plays into it so much. Everyone’s crazy on movie sets, especially the actors. And I have worked on sets where I felt like the directors didn’t respect me. I had secret vendettas against them. I still showed up, hit my mark and said my lines, but there was a bit of rebellion the whole time. It’s not a good quality to have. I don’t know, maybe there’s some part of me that needs competition in set environments.

You set the bar pretty high with Gaspar and Love. Do you consider that your starting line?

Well, technically, the first professional job I ever had was an Adidas commercial. It was a national commercial. I got paid $15,000. I took that money and flew to Europe. That’s how I ended up meeting Gaspar, funnily enough. I walked into an audition with a friend and I wasn’t even supposed to be there. Everything else sort of followed. I’d also worked with Roland Emmerich [on Stonewall] right before Love. But that was a different experience. I had a smaller role in that movie. Gaspar was my favorite director when I met him. I couldn’t believe that I was even talking to him. I was shaking on the phone. I was so nervous. It felt like I was talking to Stanley Kubrick or something. I couldn’t believe it. I grew up in Oregon. There’s no Hollywood scene there, really. Gaspar introduced me to a lot of the international film community. He introduced me to a standard of taste in cinema. He probably absorbed cinema like you do. He’s an absolute cinephile. He introduced me to all these ideas in filmmaking, and to a concept that his father bestowed upon him: never do anything for money that you’re not willing to do for free, and if you can live that way, you’ll never be a slave. That was an important thing for me to hear at 25 because I think so much of society nowadays puts a premium on amassing wealth and becoming an empire. That’s not why I got into this. I got into this because it makes me happy. It’s an impulse to play around. To dress up. To do funny voices. To write stories. So, in a way, Gaspar is the beginning. Also, he’s like the end. If he was the last filmmaker I ever got to work with, I would be okay with that. It was my biggest dream to work with a guy like that before I even started. I got so very fortunate early on. If Gaspar called me today, I would be on a plane tonight. If he wanted to make fifty more movies with me, I’d probably show up for all of ‘em. Well, maybe not fifty more of Love. [laughs]

Enter the Void was my entry into his work. I interviewed him in New York when that movie was making the rounds. I remember his exuberant energy. And it sometimes felt like he wanted to talk about everything except the thing I was asking him about—the movie itself.

The first time I ever saw him was in New York as well. It was at the IFC Center. I went to a screening of Enter the Void. I had not seen a preview going into that movie. I knew nothing about it. And he showed up to that screening to do a Q & A. I actually got to ask the first question.

What did you ask him?

I wanted to know how he shot that scene where Nathaniel Brown, who plays Oscar in the movie, looks into the mirror as he’s washing his face. He revealed the magician’s secret, but first, he was humble enough to admit that he stole the shot from two other movies. There was no ego there. He’s a very honest guy. The way Gaspar thinks about cinema and filmmaking is that life is a big, big party. He’s a very playful and mischievous person. He’s like a 15-year-old boy. He likes to have fun. He says it all out loud. Although he has a reputation for being a deranged, enfant terrible or whatever, he’s an extremely emotional and sensitive and loyal friend. I feel that his movies are always emotional, you know? I think people sometimes get so caught up in the ideas he might be investigating or a specific image that they get stuck on that. They can’t get passed it. I think he’s the most punk-rock filmmaker. I miss him, actually. You’re making me wanna give him a call.

You went deep into your collaboration with him. Maybe it’s the most intimate you’ve been with a filmmaker. Let me quote you properly: “I was completely submerged into Gaspar’s life. He shaved my head so I would look like him. I even wore his clothes, and he wouldn’t let me wash them so I would smell like him all the time. I was his mini-me.” That’s kind of intense. But I’m guessing that you liked that. It’s another thing to challenge yourself with.

Man, I was so stressed out while we were making that movie. As a kid, I was never super comfortable in my body. I was a bit of a late bloomer. So I was really self-conscious. It was a big task for me to be that vulnerable, physically. At first, it felt extremely unnatural. I mean, it never really felt completely comfortable. And when we’d have screenings, I would basically feel like I was gonna have a panic attack every time. It was intense. I had nightmares while we were filming that. Gaspar would always be teasing me—after giving me the best job in the world. As the curtains were coming up when we showed the movie at Cannes, he leaned over and whispered into my ear: “Your career is over.” He asks a lot from his actors. He puts them in intense situations. There’s not a lot of rehearsal because he wants to catch spontaneous moments. He really, really thrives on trusting people in front of the camera to do what he hired them to do. I’m friends with Sofia Boutella and we were talking about Gaspar as well. She was in Climax, and we did that Paul Schrader movie. Gaspar will get you out of your comfort zone. Everyone has to feel safe on set, but I think in life, when real drama is happening, it’s always uncomfortable. That drama should end up on screen, you know? If you’re not sacrificing a little bit of yourself when you’re acting, I don’t know if you’re really giving the audience what they deserve. Maybe this is my problem as well: I was so spoiled with Gaspar that I want to be best friends with every filmmaker I work with. If I ever worked on a Spielberg movie, I’d want to know if we were gonna go to Disneyland together.

Did Gaspar really ask you, “How do you feel about your cock being in my movie?”

[laughs] What he actually said was—well, first, he asked me how I was doing. I said, “Good. How are you?” He said, “Good.” And then he said, “How do you feel about your erect penis being in my movie?” And I said, “Sorry?” And he said, “How do you feel about your hard dick being in my movie?” As if I didn’t understand him… I said something back like, “I don’t think I’d invite my mom to the premiere.” He started laughing. And he said, “Why? She should be proud!”

You know, that might scare off a lot of actors. But not you. So what does that say about you?

I mean, I did spend a couple days really mulling it over ‘cause I was scared. I was scared to get naked. I was afraid that I wouldn’t be taken seriously if I did something like that. You know, I went to an acting conservatory. I studied with some really great teachers. I take this seriously enough. And I remember talking to a friend of mine. I was telling him, “This is the kind of movie the filmmaker wants to make. What do you think?” And he said, “I don’t know, man…” I go, “Would you do it?” And he goes, “I don’t know…” And this is a guy who’s outgoing, more so than me, like, out at night. So I said, “Well, why not?” And he goes, “I think I’d be afraid.” I remember him saying that, and I slept on that. And then it just felt like, “If I don’t do this, somebody else will. I’m gonna regret it for the rest of my life.” That seemed like such a silly reason to not do it, just because I’m afraid. There was one other thing that went into the decision. It was one of my favorite actors: Mark Rylance. He’s a giant on stage. He’s such an incredible thespian. He did a movie in 2001 called Intimacy. There’s a shot where someone puts a condom on him. So I was like, “Well, if Mark Rylance can do it, it’s legitimate. Here goes nothing.”

You once said, “I thought that maybe what I lack in experience, I could make up for in being daring.” You seem pretty fearless to me, and I suspect you had it all figured out real quick.

I mean, that’s all I had, you know? That’s the only way I could get in. I had my nose pressed up against the bakery window looking at the pastries inside, and no one would let me in. My acting conservatory didn’t have a showcase. There were no agents coming to see us. Our teacher kicked us out of the nest and said, “Go bus tables and figure it out.” That’s what we did. You’re clawing away in the beginning. You’re in New York or LA, desperately trying to get even an audition or a short film, or anyone to even look at you. The artists that came before me that I admire, some of them feel like trailblazers in the way their peers are not. They did it in a different way, pushing things a little bit further. I wanna grow as a person. I wanna stretch as a professional actor, and as a filmmaker one day. As far as I knew, I was never gonna get another chance to work with Gaspar. When he proposed Love, I was terrified, but I also thought that would be my only chance to work with him. So what am I afraid of? Failing? Then let’s fail gloriously and never look back. I feel more daring when someone’s pointing a camera at me than I do walking around in my own skin. There’s permission that you’re given to do whatever you’re allowed to do in that context. In real life, the same night that I’m afraid to ask a girl for her phone number, I’m testing the speed on my motorcycle riding home. I’m a bit of an oxymoron because I feel absolutely fearless at times. I’m like, “Everybody, look at me! Look what I can do!” Other times, I feel like the opposite of an actor: I wanna be invisible. There are times when you don’t want anyone to be able to touch any part of your personal self. So I don’t feel fearless all the time, at all. Maybe I want to chase the fear because I feel like, if I’m afraid, I might have the opportunity to grow.

Fast-forwarding to now, the most recent thing I saw you in was Eenie Meanie.

It’s a very different movie.

Well, if we want to connect it back to Love, there’s a scene in Eenie Meanie where you’re running buck naked… I mean, maybe nudity isn’t a thing anymore. What is the fear?

There are two fears that I can think of. The first fear is failure, right? And it’s such a silly fear ‘cause everybody fails. What, you’re afraid of being bad? Your goal then is to be good. Surely, you’ll fail if that’s your focus in a scene. The focus should be, “What is the objective? What’s my character trying to do?” It’s not, “Am I being a good actor right now? Do I look good in this shot?” The second fear is being typecast, like being the naked guy every time. There was a long period after Love where I wouldn’t take my shirt off for anything, even for a photoshoot. I wanted to be thought of as more than just a body. But my acting teacher, Bill Esper, rest in peace, had said something about getting typecast. He said, “Let them typecast, in the beginning at least. You’re getting a job. Once you’re established, you can break out.” I mean, I’m always seeking something different every time. A movie like Eenie Meanie is so different in tone and genre from a movie like Love or Nocturnal Animals. There are different things to try and to stretch with. Hopefully, you do enough of those things that people see you’re capable and let you try other stuff. I never wanna do the same thing. I love guys like Gary Oldman and Johnny Depp. I guess they fall into the pocket of being character actors. I like surprises. I love when actors play against their type. I love when actors do something different from what you expect them to do.

Speaking of Gary Oldman, I spoke to Owen Teague not long ago. I think you guys starred in Reptile together. Well, when Owen was in high school, he was at a crossroads, choosing between NYU and working with Gary Oldman in LA. He said that movie turned out bad.

I’m curious to know what movie that was.

It’s called Mary. Owen was like, “It got 4% on Rotten Tomatoes.” But that doesn’t matter, right? You have no control over how a movie turns out. The only thing you’re guaranteed is a new experience, be it good or bad. Every opportunity can be a new learning experience.

Always. You can learn something every day. At Stella Adler, they would ask us every day, “What are you learning?” That shouldn’t just apply to actors or moviemaking. That should apply to everybody in the world. What are we learning? The moment that we stop being curious and stop trying to learn, we’re as good as dead. Mark Twain said something about it: “Most men die at 27. We just bury them at 72.” I don’t wanna be dead. I wanna keep growing. I wanna be alive.

You know what did turn out great, though? The Neon Demon. I saw that at Cannes, and it was actually the first time I’d seen you in anything. And that came out the same year as Nocturnal Animals. I did wonder if those projects might’ve come to you in the same way. If I have this right, Tom Ford saw you in Love at Cannes and cast you in Nocturnal Animals?

What actually happened was, after we shot Love, Gaspar tried to introduce me to Nic. That didn’t quite work out, but later, I did get the chance to audition for him. He’d probably heard my name by that point. And I mostly got cut out of that movie. Anyway, once we finished filming The Neon Demon, I went to Cannes to show Love. Tom was there. I’d made an audition tape for him so I went to meet him, at a time when I was definitely moving around in those circles. God, this was so long ago… And I’m having FOMO right now, thinking about Venice and Telluride.

So film festivals do serve important functions. It can literally open doors to new jobs.

Absolutely! Are you kidding? When I walked into Tom Ford’s hotel room to have a sit-down talk with him at Cannes, he was getting ready to go to some event. He opens the door and he’s wearing a velvet tuxedo jacket with diamond buttons, and I’m wearing blue jeans and an Oshkosh B’gosh denim jacket. So I look at him and he looks amazing, and I look like absolute shit. I just threw my jacket on the floor and sat down next to him. I think he actually loved that. I think he was like, “Oh, you’re perfect. You’re just a little Oregon boy.” [laughs] Anyway, those film festivals do serve important functions. I mean, yes, you have to have the goods. You gotta be able to show up and you gotta know your lines. But man, who you know can go a long way, that’s for sure.

How did Eenie Meanie come about? And what’s the connection you felt on that movie?

Well, I think Shawn Simmons and I share a similar sense of humor. When we met, I felt that similar friendship thing I have with Gaspar a little bit. If Shawn told me to jump, I said, “Which hoop? How high?” I also trusted Shawn ‘cause, if I didn’t, it would’ve been so difficult. I felt broader than I ever was in anything else. So there is that little fear: “Is this too much? Is this too silly? Are people gonna take me seriously? Are they gonna see the work I’m doing and appreciate that I’m trying something different?” You know, I drove to Cleveland. That’s where we filmed. I brought my dog with me. I brought a big duffle bag of stuff that belonged to my ex-girlfriend—roller-skates, soccer cleats, soccer ball—‘cause I was expecting her to come out and visit me. But as I was driving to Cleveland from Los Angeles, when I got to Monument Valley, Utah, in the Navajo Nation, I got a phone call. She ended things. I was really into her, and it devastated me. When I got to Cleveland, I called Shawn. I said, “I gotta tell you something. My girlfriend and I broke up. I’m pretty messed up from it.” And he goes, “Yeah, I can hear it in your voice.” I said, “But I don’t want you to worry. It’s not gonna affect work. I just want you to know that, if I’m not exactly skipping to my mark before you call action, that’s why.” John is madly in love with Edie, but she sees a lot of issues in being with him, right? He’s the one still holding onto the idea that this can work out. He’s fucked up by it, too, but he’s optimistic. I feel like that was a quality I didn’t have to work for at all. There’s that scene on the beach where I’m talking to Samara Weaving’s character about what happened to me in rehab. A speech like that might be the kind of thing where you gotta do a lot of homework to emotionally endow the words. But I didn’t have to do anything. It was right under the surface the whole time. The reason for my own breakup is different. I feel so very different from John in so many ways. But there is still something that can help you identify with a character. If you focus on that one thing, everything else sort of blossoms from that. It’s like, “I’ll love you forever no matter what.” You keep it real simple like that. I gotta keep things simple for myself. My teacher, Bill, would often tell us that. He would say, “Find the kernel of truth, that one thing you can relate to, rather than focusing on all the things that are different.”

In its own way, art imitated life. I do believe that beach scene is the beating heart of this film.

I’m glad they kept it in ‘cause there was one version where they didn’t have that scene in there. At the same time, I think it’s one of the issues some people have with the movie. They have trouble with the broad comedy stuff and the sincere, emotional stuff coexisting. I think that throws some people. But that’s Shawn Simmons. That’s his vibe. If you watch his show, Wayne, that’s what you get. That’s Irish Catholics right there, laughing the loudest at the funeral. That’s his flavor. I felt like that scene was important because the film begs this question throughout: “Why are you putting up with this guy? Why are you still allowing him to affect you in this way?” And it’s that scene that makes the audience go, “Okay, now I see. I can see some of what she sees in him.” Without that, I think it makes the whole thing a little less convincing. And that’s tough ‘cause then you’re stuck with this guy the whole movie. If he’s driving you insane the entire time, it’s excruciating.

I love how Shawn described characters like John: “Even though they’re irritating and you want to punch them in their face, they’re so evocative. You can’t keep your eyes off them.”

It felt clear to me that, if you play this character too abrasive or too rough, it’s gonna be hard to empathize with the girl. So it was about finding the right balance. I thought about my dog a lot because she’s very in the moment. I felt like John was similarly impulsive. And it’s like a stray dog, right? No matter what you do, it won’t dampen the dog’s spirit too much. That dog will keep following you home no matter what. There was something to that.

Shawn also said he was envisioning guys from Cassavetes movies—the type who just can’t get out of his own way, like De Niro in Mean Streets. Do references like this help you as an actor?

Well, I suppose there is a little bit of Abbott and Costello in Mean Streets. The quick banter. And I suppose I don’t remember Shawn talking to me about Mean Streets on set. But we did talk about another De Niro movie: Midnight Run. That’s a comedy where two characters sort of loathe each other. They are stuck together on this crazy adventure with cars. We also talked a little bit about Nic Cage in Raising Arizona. John is Eric Roberts from The Pope of Greenwich Village a little bit. What was the other movie that Shawn always mentioned… Oh, Shawn talked about Silver Linings Playbook. That’s a very different movie, but you see all that comedy in the neurotic moments. I mean, when I watch Eenie Meanie, I’m like, “Maybe I was I thinking we were making a funnier movie than we actually were…” [laughs] Because I was really trying to do jokes the whole time.

You seem like a great study with an encyclopedic knowledge of film. Directors must love that.

Well, when my acting teacher, Bill, was alive, he told us that we need to read plays, we need to watch old movies, and we need to know the history of theater in America. I don’t think all young actors feel this way, which is unfortunate because there’s so much amazing stuff out there to learn from, to borrow from, and to steal from. If you have no references, how are you gonna be truly great? We put such an emphasis on what’s coming out right now and what that new thing is.

“There’s nothing to watch.” How often do we hear this? There’s an entire history of film.

Our culture has shifted. Our attention spans seem shorter. I probably sound like an old person saying this, but I worry about the future of this stuff. When I was 19, I really revered film and physical media. Going to places and holding objects felt sacred. Obscure movies. Pieces of art. I just hope that the next generation falls in love with this stuff again, in the same way that my class did. I mean, I’ve never been on TikTok so maybe I need to broaden my horizons a little. [laughs] Man, we really need to find our patience again. Because when you say, “Let’s go to the movies,” people go, “How long is it? An hour and a half? That’s so long.” It’s like, “You wanna watch six hours of reality TV in a row, though, right?” I love going into a movie theater. I love sitting down with a group of people. I like when the lights go down. I like being together. I don’t like going to church, but that feels like church to me.

It’s the communal experience.

Yes! That’s the whole point.

I’d love to take you back to school again. Here’s a story about the beginning of your acting journey that I found: you got into acting after buying a DVD of A Streetcar Named Desire in college. That’s when you fell in love with Brando. What do you think when you hear this?

I mean, it’s the cliché that all guys that age probably has. I wanted to be Marlon Brando. I wanted to be Marlon Brando 2.0. And I think maturing as an actor is realizing that you have your own instrument and your own stuff to bring to the set. It’s also realizing that Marlon Brando would’ve been disgusted by my fantasy of wanting to be the next version of him. You know, I met my best friend, Ben, on my first day of college. We had to take an art elective class so he suggested an acting class. It was an audition class. At the time, Ben wanted to be a filmmaker so we were making short films. In my freshman year of college, we’d be running around, breaking into rooms at the university and going onto the train tracks. Ben was the first person to ever tell me that he believed I could be an actor. He told me this one night while we were standing on a parking garage behind the dormitory. Growing up in Oregon, I thought it was such a fantasy to break into moviemaking. It felt like a far-fetched fantasy. And now I’m sort of living that fantasy.

You’re living it, Karl. You’re totally there.

It’s funny because, when I was younger, I used to think that winning an award would be the true sign of merit. If I won an award, I’d be a real actor. But I find that the best thing ever is when you’re working with someone you respect and they dig something you did. I got to work with Benicio del Toro once. It’s crazy to even be able to say that. Benicio hired me ‘cause he liked Love.

That was Reptile, wasn’t it?

Reptile, yeah. I had actually auditioned for a different role, but I was too young to play that so they hired Benicio. And then Benicio hired me ‘cause he liked something I did. It’s crazy. When I told my dad that Benicio del Toro bought me a shot of tequila, that was the first time he was visibly proud of me as an actor. [laughs] In my early days, I think the dream was just to be a working actor. You know, literally to be able to pay for groceries with acting. And I’ve achieved that dream already. There’s no one in my family that did this before me. I had the support of my mother, like, “Pursue your dream,” but nobody could sit me down and say, “This is how you read a script. This is how you get an agent. This is how you prepare for an audition.” It was a real trial and error period. And then I’ve had so much help along the way. You can’t do this without a community of support from friends and colleagues. You can’t do acting all by yourself. It just doesn’t work unless you’re doing monologues in front of the bathroom mirror. So I have to remind myself of all these things because there are times where you look around and start comparing yourself to other people. It’s like, “Wow, look how well she’s doing. Look at all the money he’s making. They’re all getting accolades.” It’s so easy to get caught up in that stuff. It makes you miserable. The life of an artist is not about that. It’s about growing at your own pace, on your own time. I have to stop myself sometimes and take a step back. I have to talk to the younger version of myself and say, “Look how great you’re doing.” I mean, if you had told the 19-year-old version of me about all that I’ve done and all the places I’ve gone, I would’ve laughed. I just wouldn’t have believed it.

Which brings us to The Running Man.

It’s the biggest movie I’ve ever worked on. I’ve never served in the military, but it felt like what the army must feel like. It’s a huge team of people building sets and blowing things up. Edgar Wright has this anime style of editing and shot selection. I didn’t realize how many angles could exist for a scene. I got that job the normal way through an audition. There was no script. They just gave me two or three scenes to read. My friend and I also made this really weird video of me walking around downtown. I tried to make a very scary video that looked like a mass shooting was about to occur. That wasn’t part of the audition or anything. I sent that in and Edgar loved it.

I was about to say—he probably loved that.

And not every director’s gonna like something like that, right? I took a swing. Sometimes, it’s not about doing the right thing. Sometimes, it’s about getting noticed. I got hired to play a bad guy in the movie. He’s really evil. I’m chasing Glen Powell. ‘Cause I knew this movie was gonna be so big, I worried about typecasting again. I don’t wanna be identified as only playing a bad guy. If everyone sees you playing the Bond villain well, maybe you’re always gonna play a bad guy. So when I flew to London to meet Edgar, I showed up as a bleach blonde without saying anything. I knew that if I asked, they’d say no. But if I showed up looking like this, maybe they’ll let me do it. Then I can be evil Karl, and I won’t be worrying about people liking me or not. Since I look so different, I can really lean into this other thing. I could see Edgar staring at my hair, but not saying anything about it. [laughs] And then he finally asked, “Did you do this for a shoot? Did you do this for a role?” I lied to him. I just made something up. I said, “I went through a bad breakup. Rather than getting a new tattoo, I bleached my hair.” He bought that and they let me keep the hair. Edgar’s lovely. The movie also has Josh Brolin, Lee Pace, Colman Domingo, Katy O’Brien, and William H. Macy. When you’re on a movie set like that, you’re not top priority. I’m just Karl. These are all learning experiences. I wanna make movies one day, so I’m drawn to filmmakers like Edgar, Alex, Gaspar, Nic Refn, and Tom Ford. There’s something to learn from all those guys. I don’t know how all the pieces are gonna come together, but I feel like I’m getting the most incredible education. I still have to pinch myself because, as challenging as it is to make a living in show business, I’m breathing such rarified air. I really feel like the luckiest guy ever. I don’t even wanna blink when I’m on these sets. I stopped bringing my cellphone to set. That’s a recent development. That’s been on the last two or three projects. I just realized that these moments are temporary. I’ll never get to relive them. So I try to be really present when I’m at work now. I’m trying to be really present in life. I’m gonna die at some point. I don’t wanna waste too much time.

See, the way you talk about death is never morose. There are just a lot more things you want to accomplish before that happens. Tell me about this movie that you’re hoping to direct.

I don’t wanna go into too much detail about it because it’s so early. But it takes place in the Navajo Nation. There’s a mission statement that I keep saying over and over. I keep saying this to my writing partner, Chris, as well: “We’re gonna redefine American cinema and what that means.” My ultimate goal is to make something that’s impactful on both emotional and social levels, in the same way that some movies instilled certain values in me as a kid. Like Star Wars or whatever. The films that made you wanna be a good person. If I could be a part of something that left that sort of impression on a young person, that would be the coolest thing ever. I wanna make something that’s entertaining and has real heart to it, you know? I know that sounds corny. I know it’s a lofty goal. Some people are like, “Come on, dude… Just make something that’s entertaining and fun.” I like fun stuff, too, but I also want to make you cry in the best way.

That’s so rare, isn’t it?

It is. I’m trying to think of the last thing that did it… I mean, one of my favorite movies ever is Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. That makes me weep like a little grandma. At the same time, it’s cool. It’s beautiful. It’s badass. It’s visually stunning. It sounds amazing. It’s a masterpiece.

What about on the acting front? We already established that you never want to repeat yourself. You would go the distance for another Gaspar movie. What is the ideal next step?

A courtroom drama, probably.

This is what I really appreciate about you, Karl. The specificity. You know what you want.

And a video game, maybe, with motion capture. That could be so cool. I’ve always heard about these amazing studios in Japan where they have motion-capture stages. What else? Anything David Fincher is doing. I hear stories about him. He’ll be looking at the monitor and go, “That car in the background… Let two inches of air out of the tires. Good. Let’s shoot that.” I mean, the obsessiveness. I love that in the same way that I love Kubrick’s attention to detail.

Endangered Species

Endangered Species Running with the Horses

Running with the Horses

No Comments