I’ve already seen AI create graphic images that are incredibly grotesque—and the way in which they’re grotesque is entirely different from the images that humans would create.

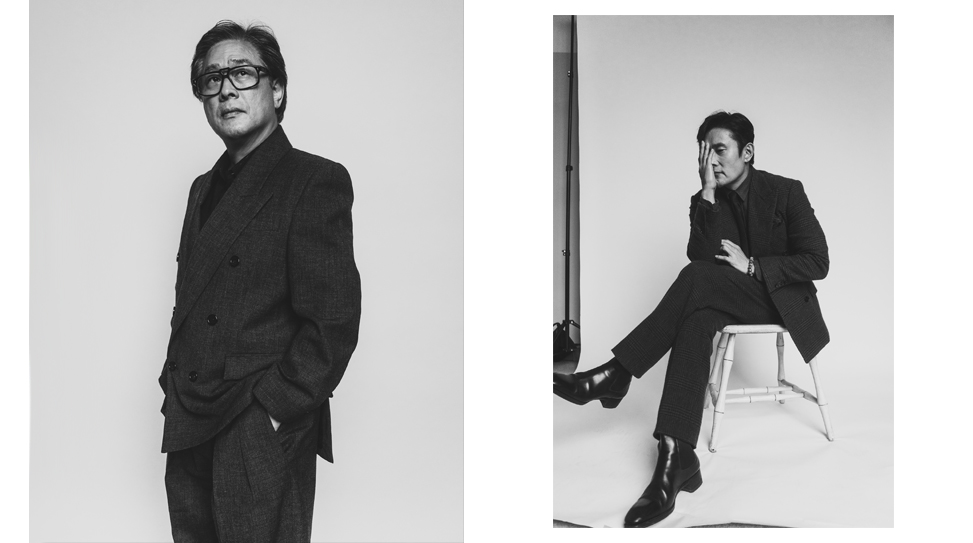

Photography by Reto Sterchi

Styling by Gee Eun (Park Chan-wook)

Styling by Lee Hye-Young (Lee Byung Hun)

Grooming by Sonia Lee at Exclusive Artists

Location: NEON

Global Brand Ambassador: Kee Chang

Auteurs are a rarity in cinema, as are international superstars. And they’re endangered species.

Park Chan-wook is one of South Korea’s greatest auteurs. From the operatic fury of Oldboy to the haunting elegance of The Handmaiden, the Cannes veteran meticulously draws viewers into psychological labyrinths all his own. His cinematic universe is one where beauty and brutality, and drama and comedy, coexist in hypnotic tension. Morality is slippery. Desire is dangerous. Cruelty and compassion are two sides of the same coin, and transcendence is often found at the edge of complete ruin. Park is a living legend whose worlds aren’t for watching—they demand experience.

Lee Byung Hun is often called “South Korea’s Tom Cruise.” As a yardstick, this measure of comparable fame is totally necessary. He’s not only one of South Korea’s most famous actors, he has become an uncontested international superstar. This past year alone, Lee took part in two global phenoms: lending his voice to KPop Demon Hunters and returning as The Frontman in Squid Game. For his efforts, Lee received the Precious Crown Order from South Korea’s Ministry of Culture, which is the nation’s highest government recognition for achievement in entertainment.

Together, they deliver No Other Choice—25 years after their first collaboration on Joint Security Area—which world premiered to near-universal adulation at the Venice Film Festival, and took home the inaugural International People’s Choice Award at the Toronto Film Festival.

The opening moments of No Other Choice plays like a dream: Man-su (Lee) has the perfect house, the perfect middle management job, a loving wife, two beautiful children, and two beautiful dogs. That, of course, means he’s in for a rude awakening. Unceremoniously laid off from his job of 25 years, he’s on the fast track to lose all that he’s worked so hard for. Now, in order to secure a new job and his family’s future, Man-su must take matters into his own hands: kill off his competition.

Anthem connected with Park and Lee in Los Angeles for this exclusive digital cover story.

No Other Choice opens everywhere this month.

[Editor’s Note: The following interview was conducted through the mediation of interpreters.]

Congratulations on No Other Choice. I watched the film in South Korea on opening day.

PARK CHAN-WOOK: Oh, really?

Twice, actually. I’m a big fan of your collaborations, going back to Joint Security Area.

LEE BYUNG HUN: Thank you very much.

You’ve now had the opportunity to screen the film around the world on the festival circuit. What has been surprising to you, connecting with audiences from all different walks of life?

PARK: That Korean audiences are generally more serious when watching the film. I believe it’s because the themes portrayed in the film might feel heavier for them. Whereas outside of Korea, audiences are able to enjoy the comedy a lot more. All movies are like this to a certain extent. It comes down to cultural differences. And even regionally across Korea, in different theaters, we’ll get different reactions. That diversity of reactions has been really interesting to observe. Whether it’s in Venice or Toronto or here in the States, we always observe something a little bit different.

That makes sense. For me, as universal as the film is and despite its global reach, it’s hard to imagine No Other Choice as anything other than a Korean film at heart. When I watched it both times, it was without English subtitles. As an American first born and raised in Korea, I was watching it through two different lenses. Some of the film’s Korean details and nuances, which I interpret differently as an American, felt super magnified: the role that men play in conservative nuclear families, the idea that you could restart a career at middle age, and our unique relationship to alcohol even. To get really specific, I thought the stakes were much higher for Man-su through a Korean lens. In his confrontation with Wonno [played by Kim Hyung-mook], when he’s cornered into breaking his nine-year sobriety, that felt even more perilous. For one thing, Korea has “hoesik,” which is woven into the social fabric of society.

PARK: Wow. Well, it is true that the scene you’re referring to wasn’t in the source novel [Donald E. Westlake’s The Ax]. But when I was originally adapting this to be an American film, that scene existed, even going back to the very first draft. So I actually never felt that it was particularly Korean. It’s only now that you mention it that I can see where you’re coming from. Maybe that’s why the American version never found investment! [laughs] In any case, I simply thought that alcoholism is such an easy trap for any unemployed middle-aged man to fall into. That’s why included it. As for the issue of masculinity, that was already explored in the original novel. And I further accentuated it because it’s true that Korean men especially tie their identity as husbands and fathers to a far more limited perspective. I believe that’s the case because patriarchal ideas that are uniquely Korean still have traces within our society. At the same time, a variation of that was also present in the screenplay when this was an American film. Perhaps these sentiments simply feel stronger or feel easier to empathize with for Koreans because we’re watching a Korean actor performing the role on screen. In the end, I find that these things pretty much garner universal reactions regardless of what country we screen the movie in, so I don’t know how true all of these speculations are.

What was the reasoning behind setting this up as an American movie originally?

PARK: It was the simple fact that the source material was American. So my first reason for wanting to make it into an American film was because I felt it would be more convenient to adapt it in America as well. The second reason was that, since this is a story about capitalism, I thought filming it in the U.S., at the heart of capitalism, would be representative of that issue on the whole.

At Deadline’s Contenders event over the weekend, you said American studios turning down the film was a blessing in disguise. It allowed you to work with Mr. Lee again. A lot of time has passed since JSA and Three… Extremes. What took so long for a third collaboration?

PARK: It was mostly because of scheduling conflicts. First of all, we have to find the right project for us to work on together. But even if we find that right project, there are scheduling issues.

LEE: [Mr. Lee turns to Mr. Park] What do you mean?

PARK: [laughs]

LEE: We’re both always aware of each other’s projects because we’re constantly in touch. It’s a shame that scheduling didn’t work out for some other things, but we got in contact early in the development stage of the Korean version of this film. I think that’s something to be thankful for.

What does this closeness, both on and off the set, afford you in the creative process?

LEE: When we were shooting JSA together, Director Park’s first couple of films had failed. So he wasn’t on stable ground. I can say the same for myself. My first four films had failed so I wasn’t on stable ground, either. As a result, there was a little less hope and a little less pressure back then. Of course, as time went by, Director Park became a master of his craft. So now, even though we have this close relationship, much like brothers do, when I go to his set, there is still tension. I’m working with a master. At the same time, because we are so close, compared to other actors, I think I’m able to share a lot of my own ideas. We have that special bond. There’s freedom in that for me.

PARK: There was no downside to working with Byung Hun on this movie. Everything about the experience was nice. He was familiar to me. We’re obviously very close. As a result, the set environment was really relaxed. Having Byung Hun at the center of the project fostered a softer environment, which made it so much easier for me to get to know the other actors as well. On set, he and I would ping pong many ideas, sometimes in a joking and lighthearted manner. Then we would get more serious while incorporating those ideas. With those new ideas, we would also make a lot of revisions to the storyboards, which I had already put a lot of work into. All in all, despite the dark subject matter, the set environment was really great. It was a wonderful experience.

Mr. Park, I’d love to take you back to our first interview. Something you’d said stayed with me: “Whether something feels like a Park Chan-wook film or not couldn’t be less important to me. I’m not at all interested in this idea of leaving my trace behind or putting my stamp on a film.” Yet, that’s what inevitably happens with auteurs. When you hear that word “auteur,” in association with you or the filmmakers that you admire, what qualities come to mind?

PARK: Well, I don’t think the word “auteur” should ever be used to simply show respect. If you really break down that word, I think a director can be called an auteur if someone discovers a consistency in their style or in the themes that are discussed across their whole filmography. In my situation, for instance, yes, I did come up with The Vengeance Trilogy [Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, Oldboy, and Lady Vengeance], but it wasn’t because I was trying to establish that same kind of consistency. It served a different purpose. Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance was a commercial flop when it was first released. As a result, I decided to come up with this trilogy idea so that, later, when people watch the other two films, they might say, “Oh, what was that other one?” and go back to watch that film.

That’s very clever!

PARK: The truth is, I’ve always wanted to make films that are very different from one another. In fact, if we were to erase my name from all of the films in The Vengeance Trilogy, I don’t think people would be able to recognize that they were all done by me. All of those films have such different styles. Furthermore, if there are overlapping elements throughout my filmography, those are unintentional. They are actually the byproducts of limitations in my capabilities.

Mr. Park, the American Cinematheque recently hosted your retrospective. When you have that kind of special opportunity to look back on your career, what observations do you make about the evolution of your work and the career choices you’ve made as a filmmaker?

PARK: I don’t know if my filmmaking journey is an evolution. I just don’t know if I necessarily got better over the years. [laughs] But it must be true in some sense since I’ve become more of an experienced artist than a technician. At the same time, my older films are evidence that, back when I was younger, my work was much more energetic. So looking back on my filmmaking career, I don’t know if I could call it progress. In the end, as I previously mentioned, I do believe that all of my films are very, very different. They deal with different subjects and explore different styles.

LEE: The fact that I’ve been able to take part in three of Director Park’s films is a huge honor.

Mr. Lee, you also had a retrospective last summer. I attended your press conference at BIFAN [Bucheon International Fantastic Film Festival] in which you explained the process of choosing the ten films that would be included as special screenings. If I remember correctly, you were keen on highlighting a variety of roles and projects from your sprawling body of work. How does No Other Choice feel uniquely different from everything else you’ve done?

LEE: In No Other Choice, I feel like I really acted to my heart’s content. It felt like I was going back and forth between heaven and hell. I was able to express so many different feelings, both quotidian and extreme. I would just say that there were so many diverse emotions to explore, and being able to show this variety in my acting in one movie was very different compared to some of the other projects that I’ve done. I was really glad to be able to show that variety in myself.

No Other Choice introduces the very timely subject of AI, which was absent in the source novel. Mr. Lee, I’m curious about the anxieties you might feel about AI. We already have an AI actress. Not only that, with your towering celebrity, AI also infiltrates your personal life. Viral deepfakes… When does AI cross into the realm of real danger for you? Is it too late?

LEE: I’ve seen AI-generated clips of myself and my colleagues a lot this year especially. I’m thinking, “I don’t remember shooting that…” Of course, they’re incredibly realistic. They might even seem fun or interesting in the first watch. But when it comes down to it, it’s creepy. The speed at which AI is developing is incredibly steep. That poses a question: what guardrails can we put in place to keep that in check? Is it possible? AI is definitely at the forefront of my mind.

PARK: With technology, there are always upsides and downsides. About the concerning aspects, I share Byung Hun’s perspective. But if I could discuss this in a more positive light, I do believe that, through this new technology, young filmmakers who lack the financial resources will be able to make films they couldn’t make before—sci-fi films and animations especially, which normally require a lot of funding. And I think there will come a day when such filmmakers will create films that fundamentally change the aesthetics of cinema. Right now, I think what’s important is to realize that we can’t stop this technology from progressing. What’s important is to keep a good watch over the threat it poses on human jobs, or from it going astray in other unimaginable ways.

On YouTube, I’ll sometimes see these very cute videos generated by AI. I really like watching cat videos. I’ll also see a video of a mother cat fighting a snake to protect its baby. We can have fun with those. But the concerning aspect of AI is when it’s incorporated into areas like pornography, or when it’s used to generate overly violent content. And sure, pornography exists without AI, but I think AI has the potential to take things into sickly dimensions that we haven’t seen before. That’s what feels so scary to me. I’ve already seen AI create graphic images that are incredibly grotesque—and the way in which they’re grotesque is entirely different from the images that humans would create. These are all important things to consider when it comes to discussing AI technology.

Mr. Park, are you open to using AI in your filmmaking? In what ways might you use it?

PARK: I have no plans on using AI in my filmmaking. I’ve even heard of people using AI in the screenplay stage. I don’t want to use it in the screenwriting stage or any other area in my filmmaking experience. But that might not be the case for some crew and effects venders. For instance, if they’re using AI for concept designs or as a tool for R&D, I wouldn’t know for sure. If they used AI to achieve any of those things, that’s what I couldn’t predict or know for sure.

Mr. Park, I believe you’re currently in development mode again.

PARK: There are some American films I’ve been developing, but nothing’s been confirmed yet. I have to work on developing some Korean films as well. I just haven’t had the time. But as soon as the promotional run for No Other Choice is over, I’ll get back to working on my next projects.

Mr. Lee, how about you?

LEE: I’m in the same boat as Director Park right now with this promotion schedule. And earlier this year, I was doing something similar for Squid Game. The only difference now is that we’ve been traveling to film festivals. This is also the first time in my career where I’m doing so much for a film’s promotion. So whether or not I get new offers, we’ll have to put that on pause for now.

PARK: Would you like me to choose for you?

LEE: [laughs] We’ll see what comes. I’ll naturally move into that next project and cycle.

Let the Right One Win

Let the Right One Win Running with the Horses

Running with the Horses

No Comments