It’s not so much about originality, but just knowing that you only have so many hours in a day. You wanna do something where it will be meaningful for you to contribute.

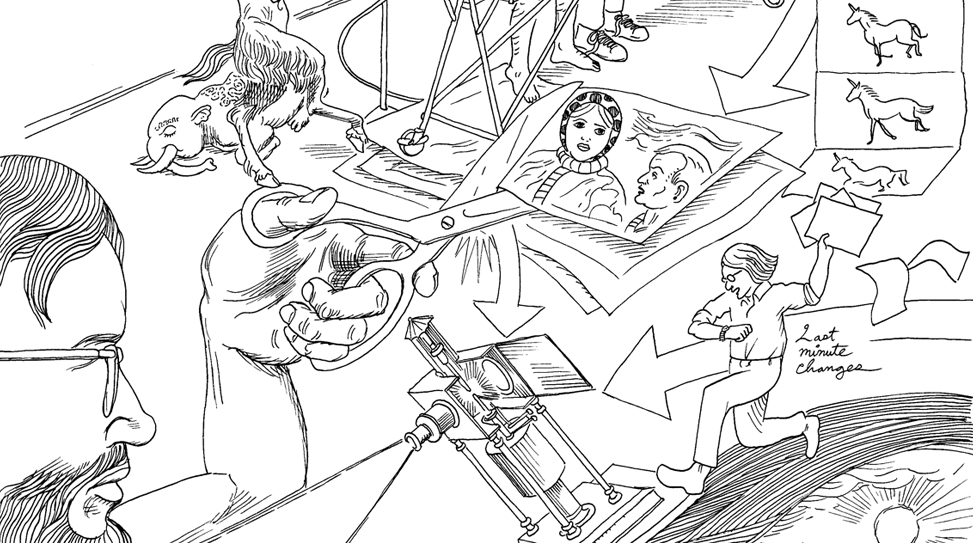

The proclivity of any outstanding outsider art, prolific comic book artist-turned-filmmaker Dash Shaw’s sophomore feature, Cryptozoo, is a bonkers cartwheel into a decidedly uncommercial mind and not the polished committee effort born from the tonally familiar confines of a colossal animation house, Disney or otherwise. Brought to life over five years with Jane Samborski—Shaw’s wife and the film’s animation director—Cryptozoo bamboozles with its singularly bizarre vision, catering specifically to adult arthouse audiences. There’s nudity, profanity, drugs, bloodied espionage, and astute philosophical ruminations. Meanwhile, the unconventional hand-drawn geometry of its fantasia overwhelms with kaleidoscopic intentionality. The bravado and ambitious scope on display cannot be overstated. Comparable works are few and far between: It’s most reminiscent of René Laloux’s Fantastic Planet. There’s also cult-classic potential here. World premiering at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival, the film won the NEXT section’s Innovator Prize.

Cryptozoo follows the globe-trotting adventures of Lauren Gray (Lake Bell), a former army brat who had suffered restless nights on a base in Okinawa until a mythical Japanese creature called the Baku devoured her nightmares. As an adult, Lauren has made it her life’s work to protect such cryptids—a catch-all term in the film to include a panoply of apocryphal beings—from poachers on the black market. But the primary evildoers here are crooked U.S. military officials with their nefarious plans for the Baku in particular, hoping to weaponize the critter to erase “the dreams of counterculture.” And so Lauren’s greatest ambition is to bring the Baku to the safety of the film’s titular zoo—not only a sanctuary, the amusement park is a cash cow for preservation efforts—which was co-founded by an aging idealist patron, Joan (Grace Zabriskie). Joining in the fight are Phoebe (Angeliki Papoulia), a Medusa-like Gorgon, and Gustav (Peter Stormare), a mercenary centaur, as they pinball from far-flung caves and mountaintops to strip clubs and Orlando, Florida.

With its wild swings, the film opens itself to any number of readings: A psychedelic paean to biodiversity, a fable about the environment, an abstract allegory of compassion, a wry metaphor for xenophobia and societies averse to otherness, and even the death of 1960s idealism—the story is pointedly set in 1967. At stake is nothing less than, literally, our ability to dream of a better future.

Anthem caught up with Shaw via Zoom to probe the inner workings of his freewheeling mind.

Cryptozoo opens everywhere on August 20.

You first caught my attention at the 2016 New York Film Festival with My Entire High School Sinking Into the Sea. Like Cryptozoo, it was so wildly different from everything else I’d seen. People have thrown out descriptors for your work like “left of center” or “idiosyncratic.” What sits with you most comfortably as far as your style and point of view are concerned?

I’m totally delighted with any of those words. Usually, a lot of those words are, like you said, “left of center” in relation to other things. And it’s not like I wanted to make live-action movies. My mission was always to make these limited-animation independent films. I had that mission very early. It just took me however many years to try and figure out how to make them and a lot of what took so long was that other people weren’t making them. If you want to make live-action movies and live in Brooklyn, you can maybe meet someone who’s done it before. That kind of makes it feel possible and gives you an advantage. But I hadn’t met anyone who’d made an animated feature independently before so a lot of it was trying to see if it was even possible. When High School Sinking played at the New York Film Festival, I was totally delighted. And I always felt that Cryptozoo is what an art film is. Even its cartoony aspects to me are very obviously pop art. Just the idea of making something that’s like a messed up or a defamiliarized Hollywood movie to me is a pop art idea. I’m very happy to be included in anything.

You’re so often asked about your influences and that has naturally opened up conversations about many things, including Winsor McCay. I actually grew up on Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland, but had no idea that animated film had its roots in comic strips until you brought it up. That coupled with the Baku legend, which takes center stage in Cryptozoo, I wondered about your relationship to dreams. Is that a recurring theme across your works?

Well, when I came across the Baku, that’s when it really felt like I had a movie idea and not a comic idea because I feel like movies can replicate a dream state more than comics do. Comics are always kind of outside of dreams. It’s about decoding them, often quite literally like, “Do I read this bubble before I look at this face?” There’s an analytical brain that’s different to reading comics. With good movies, it’s like you’re in this darkened room and, ideally, you’re somehow transported. Then the lights come up and it’s like you wake up: “Wait, where am I? Oh yeah, I went to see this film at the Angelika.” A dream-eater felt like a perfect kind of movie-being.

I know you spent some time in Japan. Is that when you first became aware of the Baku?

It wasn’t. It was only later. I was there when I was like 16.

So where did it all start?

Like for lots of people, I had a Greek myths book growing up and those Ray Harryhausen films. Then I played D&D until around middle school. But years later, my wife Jane [Samborski], who painted most of the cryptids, had an all-women’s Dungeons & Dragons group when we lived in Brooklyn. And because it was Brooklyn, there were a lot of women from all over the world that came to the group. Often, they had just moved to New York and that social circle was an early beginning to making friends. I would leave the apartment while they would role-play. That was right around the time I was writing Cryptozoo, wanting to write something for Jane. I think that kind of inspired the cryptids, the mostly female cast, and the globetrotting nature of the movie. I have to say that, looking back—the movie took so long to make—I was kind of looking at cryptids then from more of an art school perspective: the unicorn tapestries at the Met Cloisters and all of these depictions throughout time. I had an interest in them from more of an art history perspective, which was years removed from the initial childlike appreciation of drawing monsters.

I’m fascinated by the sincerity with which some people continue to embrace cryptids. You can go on YouTube and easily find modern-day adventurers who have organized their entire lives around this stuff. There are endless roadside attractions all across America. It’s my feeling that the chase of a life less ordinary is something the film articulates really well.

Cryptids are the imaginations of our world. Also, my brain probably leans more into thinking about them as the radical artworks of our culture. Then it’s about how often, in an attempt to introduce these radical artworks, good intentions end up hurting the artworks. If the artworks roam free, they’re more powerful and wild and dangerous. They eat each other. It’s a chaotic thing that could be harmful, but fruitful. So yeah, I think of them more as strictly imaginary beings.

You’ve been asked about the “unfinished” look of Cryptozoo. That got me thinking about limitations versus intentionality within the parameters of your practice. This is obviously quite a spectacle—a big movie concept—told on a certain scale. I wonder what the biggest challenge is that comes with that, and conversely, what you find really freeing about it.

I’m really glad you ask that because I feel like that’s a big part of my movies. I hope that when they’re rocking, it feels like an experimental blockbuster movie: this beautiful less is more kind of feeling you get from the smallest thing or one drawing. To me, the spirit of independent cinema is the power of less is more. It’s about the power of harnessing the cards you have in your hand. Whatever you’ve been dealt, you make use of that to huge ends. Also, because that was always the idea and always the goal, that’s probably the main reason why I’ve been able to make these movies. I’ve met other people who would loved to have made animated movies, but they just think, “I’ll never have millions of dollars and live in LA and get a studio to do it.” So you know, it’s like, “What am I gonna do?” Whereas for me, if you look at the shorts that I made before High School Sinking, it was stills. It was very, very limited. The goal was to harness limited animation and think of it as a unique mode that I could continue with and to be inspired by. To technically answer your question, there’s a bunch of Maysville, Kentucky backgrounds in this movie and there were too many for me to hire someone else to do them. I could’ve come up with some great painters who would be happy to have the money to paint those background, but we just didn’t have it. So then it comes to me: “Okay, so how do I paint these things?” Then I come up with some way to execute them. Whether or not my way is better or worse, who can say? Sometimes the problems that need solving equals exciting and different things that you haven’t seen in a movie before. Other times, probably, it’d be better if I had some money to do it a particular way.

I’m going way back in time now: there was an interview published in The Comic Journal in 2008 where you basically admitted that you don’t normally like to collaborate. Your features obviously require a very lengthy and intense collaboration with somebody like Jane. Has your attitude changed in the intervening years or is that something you still struggle with?

I definitely learned a lot. In 2010, I went to the Sundance Lab and that was a crash course in learning how to communicate with other people—period. So I got much, much better. In 2008, I was still staring at the floor while talking to people. I don’t think I’m ever going to be as good as some directors where social skills are concerned. But I’ve definitely gotten better at it. [laughs]

Going back to the Baku, what I love about that legend is that it’s said to come and take away your nightmares, but if it remains hungry, it can also devour our hopes and desires. The movie explores this very thin line. If you get too curious, we see that our livelihood might be at stake. If you interfere too much with the natural world, things will get out of hand. Like we’ve been talking about, there’s a lot to take away. Have there been audience interpretations that have really surprised you that you didn’t intend or think about?

Yes, there’s always someone who comes up after and says something that’s very surprising. It’s been really, really fun to tour the movie and it’s played some really beautiful places. This guy in Richmond, Virginia was like, “All of these mythological characters—centaurs, krakens—aren’t copyrighted. They aren’t attached to any corporations. Then our modern myths that are like these same beings—the Hulk and all these Marvel characters that are now attached to theme parks—are all connected to these giant corporations and copyrights. Your movie is the exact point when the mythological beings become copyrighted. Cryptozoo, which is set in the late 60s/early 70s is that moment of transition.” That hadn’t occurred to me at all. I thought that was a really funny observation. And that was probably kind of baked into the things I was thinking about anyway, but it was still interesting. At the internal screenings for High School Sinking, for acquaintances to kind of figure things out, the notes were always like, “I have no idea what’s going on” or “It’s confusing what space they’re in.” So we had spent a long time adding information and shots to explain where the characters were—just the nuts and bolts of filmmaking. But with the very first shared screenings of Cryptozoo, people were always taking about the more interesting stuff: interpretations, possible allegorical readings, and how one thing seems to mirror something else. That was really exciting. It felt like the movie was holding a lot of things in it while still engaging with audiences for an hour and a half, I hope, on the level of an enjoyable spectacle ride.

Sometimes there are discussions about how it’s no longer possible to be totally original because everything seems to have been done. But then something like High School Sinking and Cryptozoo comes along. I suppose this is sort of a big question: what are your thoughts on originality as an artist? I wonder if it’s something you actively wrestle with.

The only way that I really think about it is like this: like a responsible citizen, you wanna go where it seems like you’re needed. In my love of the connection between limited animation and independent cinema, manga, and fine arts stuff, I thought, “Oh, there could be a movie like this and no one else is doing it.” Maybe had I seen that a lot of people were doing it, I would’ve thought, “They got it covered.” I don’t tweet because Twitter doesn’t really need me. [laughs] I’m not needed there. So it’s not so much about originality, but just knowing that you only have so many hours in a day. You wanna do something where it will be meaningful for you to contribute.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments

Comments are closed.