Certain things scare me, but they’re probably not what one would expect.

Peter Vack knows how to make one hell of an impression. Take his 2017 directorial debut feature, for instance. Aptly called Assholes, the actor-turned-filmmaker brazenly invited unwitting audiences into his world of X-rated romp—so that you might spend a chunk of its running time watching his characters’ faces turn into the movie’s title via prosthetics. And that part of it is tame, all things considered. Naturally, upon seeing this, we invited him out to lunch.

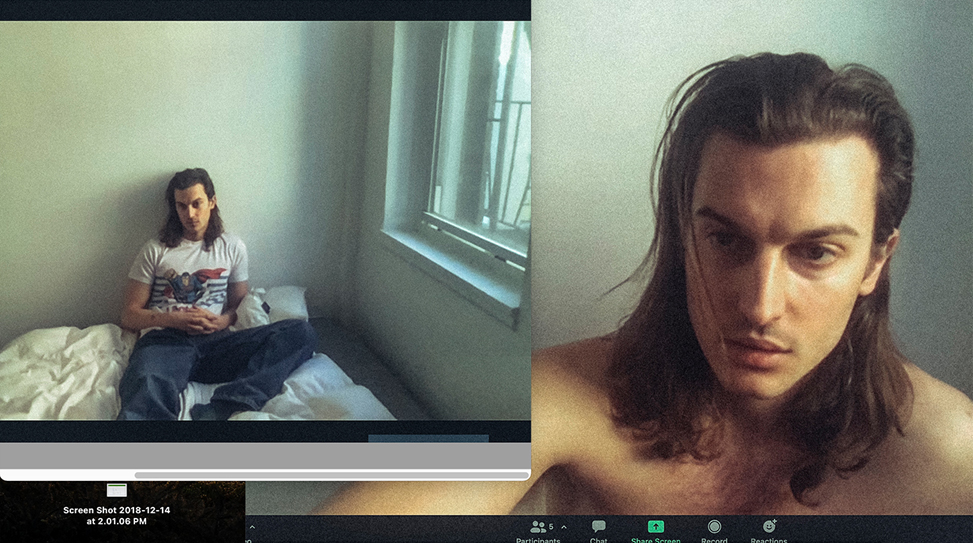

Last week, Anthem reconnected with Vack via Zoom to discuss his latest role in Ben Hozie’s PVT CHAT, which only confirms what we’ve known all along: he is a fearless performer who gives new meaning to committing for the camera. Here, he plays Jack, whose compulsive nature in online gambling is only rivaled by his growing fixation on Scarlet (Julia Fox), the camgirl of his dreams.

PVT CHAT is in theaters on February 5, and hits On Demand and Digital on February 9.

I vaguely remember you talking about this project from before because Buddy’s [Duress] name had come up in conversation. When did you go film this?

We shot, I think, the first chunk in the winter of 2018. But we came back and did some additional days in 2019.

I think it would be so hard to attempt this now. For a long time, really.

For what reason?

COVID-related reasons.

Yeah, it’s true. I mean, I have done a few productions since COVID. The protocol is pretty strict. In a way, I think we could have made this movie now because so much of it is about people isolated. But certainly, it would’ve been a little harder.

This is a brave performance. Did it scare you going into it? Does anything scare you?

Certain things scare me, but they’re probably not what one would expect. For example, the easiest thing to mention would be the nudity. That doesn’t scare me. I’ve somehow found a way to not be modest when I’m acting. In life, I do feel modest. There are people who I feel have an exhibitionistic quality to them in life and I don’t relate to that. I don’t want to take my shirt off necessarily. I will, but I’m not the first one to do it exactly. I feel 180 degrees pivoted from that position in the context of my work because I as an audience member am so attracted to movies and art where I feel modesty is not in play. What you get when you feel that performers are not feeling self-conscious about being seen is this unobserved act, which is why I go to art. I want to see something that feels like there was nobody watching it and the performers weren’t conscious of themselves being exposed, in the same way as in life where we’re exposing ourselves constantly, whether it’s literal or figurative, to the people we’re intimate with. If I sense that the performers’ own eyes are on them with self-consciousness, that is what can break the illusion. So I’m always trying to and have managed to do that—knock on wood—mostly successfully. I mean, that’s really up to the audience to decide, but I, Peter, do my best to, if there is ever a question of modesty, go “that’s the enemy of my work.” Again, I do have modesty in life so why would I even want to bring my own baggage with me into acting? I’d rather identify the baggage of the character and play with that.

I’m continually surprised by your ability to disappear, especially considering that I know you in real life. That never interferes with the moviegoing experience. Your presence is never the thing that pulls me out of it.

That really is the highest compliment you could give me.

How would you describe Jack? Maybe he exists in your mind under more uncertain terms.

In terms of the way I see him, it feels somewhat opposite to the job of the actor where you put labels onto him before the shoot, except that I really did relate to him as someone who has a capacity for a naive obsession and preoccupation with a romantic other. In a way, if I were to label him as anything before we did this, I would label him as a hopeless romantic. I’m not exactly sure if that’s how the audience receives him, but that was for me the way in. I probably did feel, as Peter: “No, Jack, please don’t be this cynical or nihilistic about human interaction.” It’s easy perhaps to think that Jack is a cynical, perverse guy. But with his cynical attitude—and I’m speaking very specifically about this rhetoric the character says a few times about how all of human interaction is transactional—I only believed that to a certain degree when playing him. Whether that was conscious or not, I thought it was a protective ideology, guarding me against my actual optimism. I suspect a lot of people that I meet who have these very cynical, nihilistic fronts—and I’m probably not always right—use that as armor, and beneath that is actually a very optimistic person who is desperate for love and connection. I think Ben’s [Hozie] movie is about that because on the one hand, you have Jack saying everyone is basically an ATM to a person, so much so that he can only really even interact with Julia’s character with this technological intermediary between them. But he’s also—once she opens up to him and shows him her art—a kid with the biggest heart. He is genuinely wanting to connect and find love. His actions are almost diametrically opposed to the rhetoric that he aligns himself with.

Those are the instances where Jack’s reactions read most genuine. His face lights up when Scarlet talks about her art for the first time. He’s so delighted when she asks him about the—unbeknownst to her, fictitious—app he’s developing. Since that is at odds with the rhetoric he espouses, that every relationship is exploitative, he is a contradiction, as we all are. Similarly, it’s interesting that he would flip a coin to decide, every time, whether or not to enter the massage parlor. As impulsive as he is with the online gambling, for instance, he’s methodical about other things. He has rituals that make sense to him.

Right. I do think there is something behind that, but a lot of this I didn’t really consciously think about, you know? Some of acting is just saying the lines and letting the themes speak for themselves. I wasn’t really thinking about this at all in the moment, but now with some perspective I would say that, like how he feels relationships in life are a bit of a game, he has made that into a game as well, as a way of protecting himself. It’s like, okay, he has the impulse to go and have a happy ending massage. But rather than just totally follow that impulse, because that might create some feeling of inner-anarchy or chaos, he puts it through this rubric that’s similar to the gambling in a way: “I’ll just leave it up to chance—50/50.” Jack is someone who’s comforted by numbers and statistics and all this sort of machinery that makes the chaos and uncertainty of life feel predictable. I think it’s just a way of giving his impulses some framework so that they’re not just gonna take him over, even though he is sort of taken over by his impulses.

PVT CHAT has so much to do with boundaries. It’s as much about physical boundaries as it is about imperceptible ones like trust and sexual deviance. Looking at the world at large, do you think there will be some permanence to how we are currently living when the virus is finally eradicated? For instance, do you think we will have grown more suspicious of one another in a way that’s really permanent?

That’s a good question. I do think that there will be some texture associated with this COVID lockdown that we will not so easily lose. The closest thing that I can point out, the knowledge that we won’t be able to come back from—and I don’t know what the ramifications of it will be—is this feeling that we are really always sharing particles with each other. The virologists and scientists among us knew this clearly, but I didn’t. I mean, I wasn’t thinking that when you and I were chatting a couple of years ago over food in Korea. It didn’t matter that neither of us were sick. We were still breathing in each other’s particles! It’s kind of amazing that we all know how much of each other we’re really taking in, even when we’re just sitting and chatting over a meal. We don’t have to be making out to exchange particles. That is a really intense idea and subject and metaphor and image. I’m not sure we’ll so easily be able to undo that from our collective consciousness. I guess the most obvious, most basic outcome of this new knowledge is that, hopefully, if you’re sick you wear a mask. Some cultures have that better than Americans do. I think moving away from just practical application of that knowledge, there is a physical application that will just be around for a long time. When we go to parties again—and we’ve all probably broken the rules a little bit—we’ll really know that we’re sharing more than just jokes.

There’s a great scene in the movie where Scarlet is invited to watch the rehearsal for her husband’s play. She quickly realizes that it’s incredibly revealing about their private life and her circumstance as a camgirl in particular. When a movie is self-reflexive like that, you naturally become very aware of the film’s artifice, and this is something I felt strongly watching Assholes, too, because it’s a challenging film. You become very aware of the transaction that’s being made between the maker and the spectator. I wonder if that’s a through line you find interesting to explore on both the acting and filmmaking fronts.

Oh yeah, that’s a great question. I’ve been thinking about this recently a lot. Because I am an actor first in a way and then came to filmmaking, I sometimes wonder if I’m too interested in this well-trodden, post-modern gesture of calling attention to the artifice of the art—like [Bertolt] Brecht, who was famously the first to do this where he would have the actors change costumes onstage and would not hide the machinery of the play because he wanted the audience to be very conscious of the idea of a play. There are certainly movies and books and such that have no meta qualities to them whatsoever, but it is worth mentioning that in this moment where we really are living in the future, where we all have screens on us at all times. It’s not the old model where it’s like “I’m only an audience member and I have no involvement with cinema.” Everyone is a cinematographer. There’s less magic in the machinery of movies and TV than ever before. So I think there is still room when making art to talk about meta aspects. This conversation has this meta element. I’m aware that you are not here, but on a screen. I know we’re really talking, but it also sort of feels like I’m watching a movie of you. I have made it so that I can’t see myself because I can’t handle that, but I know some people have to see themselves when they interact on Zoom so that they’re comfortable with the way they look. So we’re talking to people, but seeing our own image. They are not a body, but an image on a screen, and this is a real conversation happening in real time. I don’t have a great conclusion to this—I’m just pointing out things that remind me of these Brechtian, post-modern elements in art that feel like they have now infiltrated our lives. There is still a reason for exploring themes of meta in work.

You once told me that one of the reasons for writing Assholes was as a reaction to being continually cast to play assholes. That’s pretty meta.

On this show that’s out right now on HBO, Love Life, I don’t play an asshole so I was really excited to do that. Sometimes I’m asked to play a nice guy. I remember a professor saying this in acting school: “a lot of this comes down to the feeling that people have when they just look at a photo of you.” Perhaps more people when they just look at a photo of me, they think asshole—not nice guy. You know, I’m a nice guy!

You are one of the nicest guys.

[laughs] What does that even mean? I just did a movie where I played a prickly character. It definitely is still happening to me, and I don’t mind it. When I said that I’m in Assholes to comment on typecasting, it was true, but it was also a little flippant.

Do you have another feature lined up?

I wrote a novel over the past five years. Who knows if it will see the light of day. I might just self-publish. And I do have a film. It’s not really a direct follow-up to Assholes, although it just would be because I guess I’d be making it. It deals with the audience, spectator, social media as performance—those things are definitely in there. I think because I am so familiar with the machinery of filmmaking, any time I do go to the filmmaking role I just feel like I’ve been polluted by the fact that I’m an actor in a way. I mean, I would love to do a very clean and simple story that doesn’t have any self-conscious eye on it, but I think because I, Peter, as an actor, have had my conscious eyes on filmmaking for so long, making a film just has that in there no matter what—right now at least.

I feel the same way in that film school trains you to deconstruct movies, often beyond reason or rationality. It’s been a long time since I’ve had a movie just wash over me, where I’m not thinking about the machinery you’ve been talking about. That’s a thing of the past.

I agree with you. I wonder if there will be a new wave of work that, somewhat in contrast to the way that being online feels very meta and ironic, will be a total departure from it—where we see stuff that’s actually rather earnest and sincere. I mean, in literature they call this The New Sincerity. That’s a thing. I’m curious to see if we will have these very cynical, ironic takes on society or if we’ll have more earnest, romantic takes. There will always be a mix of both, but it’s impossible to know really. Because if we feel like we’re living in this highly cynical and mediated reality, that might produce work of a different approach. I’d be curious to see that work, although I do really like both. I’m not really saying one is more relevant than the other. I just think that it’ll be curious to see how, especially if the youngest filmmakers now have grown up with no memory of pre-internet time, what those films will feel like. Really, I’m curious to see.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments

Comments are closed.