You’re in the hand of the universe and you have to be open to that like water flowing down a stream or over a body of land. It just goes where it goes and you gotta flow with it.

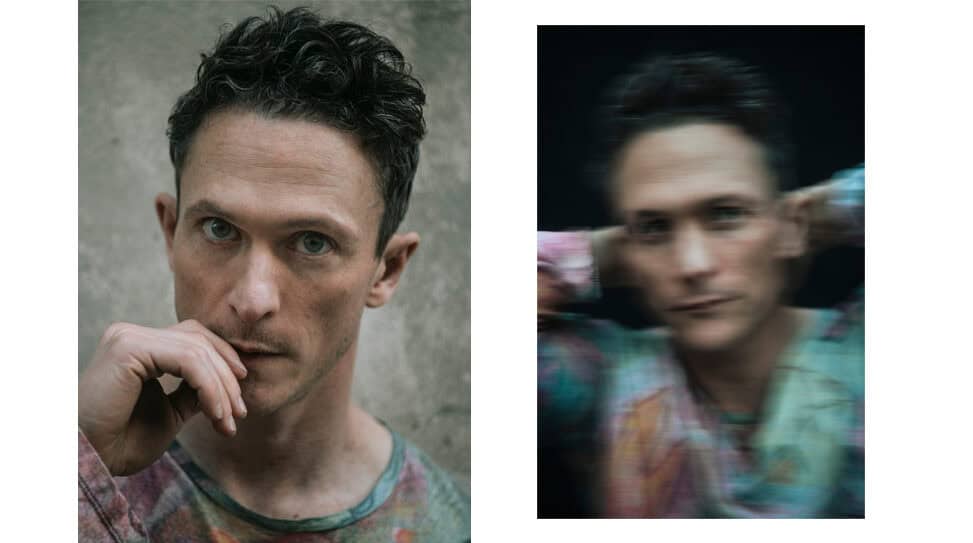

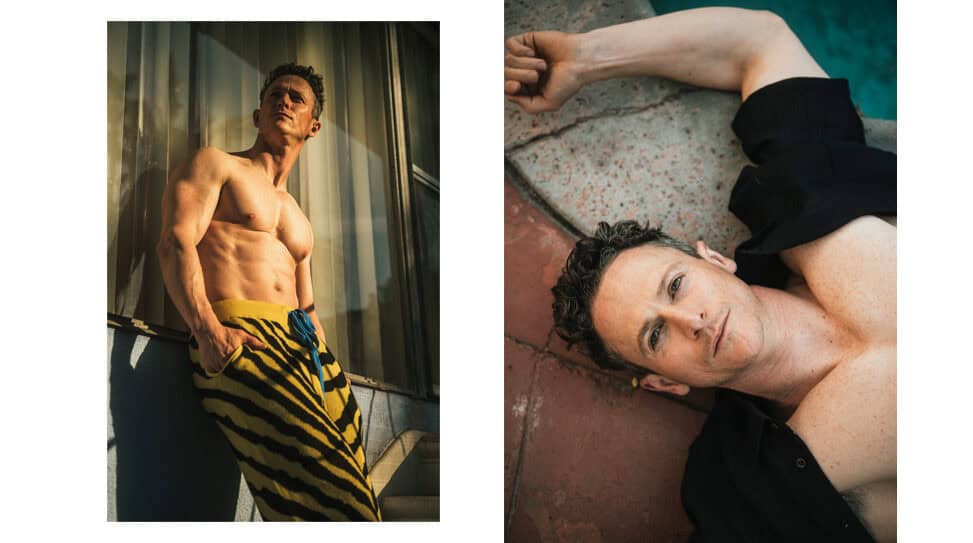

Photography by Reto Sterchi

Styling by Regina Doland

Grooming by Sarah Dougherty @ Atelier Management

Today, in conversation with Jonathan Tucker, we broach the subject of grooming and predation. This might sound heavy for an otherwise jovial exchange, but the Boston-native is here to talk about Palm Trees and Power Lines, the debut from first-time feature filmmaker Jamie Dack—one of the most acclaimed films to come out of the 2022 Sundance Film Festival. The film, for which Tucker is currently vying for the Best Supporting Performance gong at the Film Indepedent Spirit Awards, follows the five stages of grooming. It is a modern-day cautionary tale about how even a marginally vulnerable person is susceptible to psychological coercion and sexual exploitation.

The film opens in the languid stretch of one teenage summer. 17-year-old Lea (Lily McInerney) moves through the world without affect, listless and uninspired by an unimpressive group of no-accounts that she hangs around with, not to mention her indifferent single mother (Gretchen Mol) who clings when she’s lonely and disappears just as frequently. It’s no wonder, then, that Lea finds herself drawn to Tom (Tucker), a handsome 34-year-old who flirts with expert cunning, en route to grooming her. Palm Trees and Power Lines derives its power from the uncomfortable degree to which we’re compelled to empathize with Lea as she makes a string of increasingly perilous decisions. The things Lea does not yet understand are never obscured: possessiveness that isn’t romantic but alarming, and the sketchiness of a man who spends all his time with an underage girl. Dack authenticates Tom’s allure for Lea with a steady hand, while still consistently puncturing it.

Anthem recently met up with Tucker in Hancock Park for an in-depth conversation and photoshoot.

Palm Trees and Power Lines hits select theaters and VOD on March 3rd.

I love what we have going here, Jonathan, checking in with each other every now and then.

That’s right. It’s nice, let’s keep that going.

I’m rooting for you at the Film Independent Spirit Awards. This is the first time that the acting categories have gone gender-neutral. It’s an impressive and eclectic line-up of talent.

Yeah, it’s interesting. I think there’s some people who are very likely to get it, but if I was actually really in competition, I would be frustrated by the gender-neutral category, only because you have less of a chance of getting it. You go from one in five to one in ten. And awards for best acting? I don’t really quite know what that means. What I do know is that it has given us a platform, putting a light on a movie that I care a lot about, and particularly on three women who’ve done remarkable work to get the film to where it has been: Jamie Dack, who wrote and produced and directed the movie; our producer, Leah Chen Baker; and our beautiful actress, Lily McInerny. Then there’s Sundance, Deauville, BFI London, Torino—all these film festivals that have given us a little attention. It just goes such a long way, especially considering the limited budget that the film had.

Because whether awards are important to the individual or not, they’re going to get eyes on the respective films—more than you already have. In that respect, it can only help you.

A hundred percent. And I wanna make movies with Jamie. If you told me that I just have to take a year or two before each project, but I get to make a movie with her? That’d be a very good life.

And “supporting actor” feels unjust to me. You’re very much front and center in this film.

You can be both a supporter and a leader. I had the opportunity to bring the experience that I’ve garnered over the past 30 years now, and support these women and leaders in their own right.

When was this film presented to you, and what sold you on it?

I got on probably a year prior to filming, at least because of Covid issues. I was on a TV show. The moment I met Jamie via Zoom, I knew she had something to say, and I knew she’d execute on it.

This is a tough role. You’ve previously described the material as “upsetting,” and rightfully so. I know it was important to Jamie that the film explores the different stages of grooming.

I think the human condition that allows for manipulation, and the gray area between a dance of seduction and grooming, is what we were trying to find and play with. Oftentimes, that can mean giving somebody the opportunity to leave, both physically and spiritually, so that they feel safe. In many ways, I felt like the script was disturbing, but it was in no way comparable to the feelings I had in watching the movie, the final product. Jamie groomed us, as well as the audience—I found that in both the script and the film—because so many times during the reading of the script and in so many moments in the film, your intuitions are like, “Hold on a second, there’s something wrong here.” And yet, we’re able to rationalize it intellectually with whatever Jamie then offers next to make you feel like it’s okay, even though you know it’s not right. So when your intuition is proven to be true about this character or about this relationship, it makes it all the more powerful.

I would think the sensitive subject matter requires an incredibly open line of communication.

I felt comfortable at the outset, a year before we started filming. As we approached production, I was still feeling super comfortable. But just a few days before we started, as we got into rehearsals, I had a bit of a panic: How do you tell a story like this and allow this teen to soar, and have spontaneity within the context of the film, but also where your dance partner feels comfortable, particularly in physical or sexual situations? I’ve done a lot of those scenes for so many years and have always taken my role in that work seriously. And by that I mean to say, make the other person feel comfortable so that I, in turn, can also feel comfortable—so that the work can be magnificent. We were in such a heightened place, and rightfully so, in the #MeToo era. I had this feeling that maybe I could do everything correctly and then somebody might feel uncomfortable, without, in a sense, understanding my intention. It could be misconstrued. And those concerns, which came late and were debilitating for a good few days, were really addressed by Jamie and Lily. I think the best example of it was right before we started shooting the first scene when Lily reached over, putting her finger on my finger just as they called rolling. It was such a small gesture that said, “Hey, it’s okay.” I think you have to prove a little bit of who you are to people before you take a jump like that. I think it’s important and it certainly was for us. And once we ripped that ticket, we were off.

You’ve previously talked about the irony of feeling vulnerable being the male lead on a predominantly female set, especially when you’re playing a monstrous, predatory character.

I have no issues around trust, really, other than like, I don’t want you to use some shot that is fully explicit that wasn’t contractual. And I am keenly aware that all of us are different and that we can store trauma in different parts of our body. The traumas that women have experienced or men have experienced are things that they either do or do not want to talk about if it’s something to protect, whatever it is. It’s really not my business to get into anybody else’s personal story. I just want to be respectful of them and to be able to set very clearly what the framework is so that we can really jump. And that, of course, also means that the framework can change on the day. If somebody decides that they feel uncomfortable with something, it’s all good, as long as they have the opportunity to communicate it to somebody so that it can get communicated to me. There wasn’t a real feeling of vulnerability around playing a character like that in the height of the #MeToo era in Hollywood, on a low-budget production with a young actress—this is her first job, really—and a first-time feature director. I just really had to hope and pray that my intuition about Jamie was right, and it was continuing to prove right. So you need to have some faith at some point in life.

If you were to only watch the front half, or the first two-thirds, you can still believe that Tom is a great guy. That’s entirely the point, right? To echo what Jamie said, even a marginally vulnerable person is susceptible to predation. Tom is captivating, and you play it so well.

That’s probably the most concerning thing, and the truth around these sorts of relationships and people. The truth is, they’re not binary. It’s not like you can immediately spot the bad guy. This is not that action movie where all the good guys wear one color and all the bad guys wear another. And there’s probably real personal trauma in Tom’s personal history. I’m sure he got here for some horrible reason and, you know, the cycle continues. But we always want things to be black and white—it makes life easier. But none of it ever is. The real evil in the world always presents itself with the most exquisite mask. That’s why it’s so petrifying for parents, for people who find themselves in these positions: the insidious nature of it, the manipulative nature, the shape-shifting. That’s why predators oftentimes go after vulnerable people. They’ll go from flock to flock and target that one who’s the only one that could say anything, but doesn’t have the voice to express it.

If there’s anything good to say about Tom, he’s very good at what he does. It makes you wonder what he could excel at, if he chose to apply his talents elsewhere in a positive way.

That’s the trouble with him, and that’s what’s so horrifying about abuse. It eats up so much of the good in people. The people that have been abused end up allocating so much of their energy towards trying to understand why it happened to them, versus shining their own light out unto the world. That’s what’s quite tragic about it. That’s one of the ancillary tragedies of abuse.

So in what ways did you relate to him?

Well, I think he’s a romantic. He understands romance: the courtship, the falling in love with somebody, the curiosity that’s required, the efforts that are required. The closer he is to me personally, the better the performance, in some respects. That one small part at the end, that’s not me. But if there was a lot of him that wasn’t me, it wouldn’t be, I don’t think, as strong a story.

I once asked you if you had modeled your Kingdom character after anything in particular and you gave me this laser-focused answer: Sam Rockwell’s screen test for Confessions of a Dangerous Mind and Christian Bale in The Fighter. Did you have a blueprint for Tom?

Tom is much more similar to me than Jay Kulina, so having that vulnerability of just saying, “I can do no other,” to quote Martin Luther, was the work I had to do and sometimes that can be the hardest thing for an actor. I feel more comfortable putting in the mountain of work to create somebody that’s a few steps away. To be myself, in many ways, for so much of the character, was a challenge—knowing that I was enough. I always like to go to animals and I think there’s a bit of that. There’s a sort of fox in there, to be cuddly and cute and playful. Then there’s the nibbling, the teeth, the biting, the animal that can do real harm and kill chickens, that sort of thing. It was an interesting way for me to start looking at a character like this. Even with a cute dog, you’re playing with them, then when they see someone and they get frightened, they’re showing fangs—that’s a totally different animal. So that was an important part of this for me.

We’ve talked about your animal work before, so it was interesting to hear Lily bring it up in your group interview for Collider. I suspected that it was something you introduced her to.

We’re all physical creatures. Doing some of that with her early on, it would be an afternoon session, the two of us roaming around on a stage pretending to lick raindrops off of rose pedals, which is just so profoundly embarrassing to do with somebody you’ve just met. [laughs] To fully commit to those sorts of scenarios, it’s just mortifying. But it makes you totally open to all of the stuff you’re gonna end up doing in the movie so we accomplished quite a bit in a very brief period of time. I mean, look at how many people huddle in their shoulders because they simply don’t want to be exposed, you know? The amount of hiding we do physically is outsized. So to be fully exposed is something that provides two actors quite a bit of runway when you get to start shooting.

As you have continued to do, I also want to sing the praises of Lily. She has a freshness that actors never get back ever again. Did working with her remind you of your early beginnings?

Great question, dude. You’re totally right about fresh quality. It actually reminded me a lot of what I saw when I was working with some of the younger actresses coming up like Natalie Portman or Kirsten Dunst. They had, at a very young age, an ability to be totally pure, curious and magical. They were cognizant that they could possess that, too, and committed to it. And it brought me back to some of those early days of being out in Los Angeles and New York, being in acting classes with some of these wonderful young actresses as they were finding monumental success, earlier than all of their colleagues, including myself. I was reminded of that quite a lot and that’s where I went back to. It’s also a great reminder of how resumes really are lovely in some respects, but as long as you have a basic understanding of the camera, what’s most important is the ability to just be a wonderful sparring partner or a quarterback receiver. You just want somebody who is fully committed and willing to take risks, willing to not be intimidated by their lack of experience or by whatever the material is asking them to do. In that respect, Lily’s like an A-list actress.

Is that what you hope to impart on young actors?

Look, there’s a lot of camera stuff. There’s just a lot of things about how to conserve your energy in a day. Lily and I would have lots of conversations about the sizes of lenses, little things about hitting marks, where to hold props in a frame, coming up with new ideas and figuring out how to find your way back into a scene when dialogue or things happen unexpectedly, when to hit up craft service and when not to, how to figure out how to walk off set and find good food if you don’t feel like it’s the right meals. It’s a whole life, man. For me, it’s 30 years now of literally paying dues to the Screen Actors Guild so it’s always nice to be able to share that. But you also don’t wanna be condescending because the quality of Lily’s work is magnificent. She was already figuring it out when I got there. She was always picking up on little things because she was asking the questions.

Something that’s less tangible, and what seems to crop up in our conversations a lot, has to do with spirituality. It’s important to you in your day-to-day so it must carry over into the craft.

Well, I think you’re just not in control. If you believe in God, you just observe how the world works, man. Have you ever seen someone get cancer? Some people take a walk off the sidewalk and get hit by a car. Some people find out they had a trust fund. Some people lose all their money because their bank got robbed and it wasn’t insured. Life is so unfair. I think faith without work is passive consumption. I also think that, at a certain point, you realize that you’re in the hand of God. You’re in the hand of the universe and you have to be open to that like water flowing down a stream or over a body of land. It just goes where it goes and you gotta flow with it. Dam up that water all you want, it’s gonna go somewhere. Any director who thinks that they’re gonna execute exactly what they wrote on the page in a script is an inexperienced director, or a director who doesn’t have talent. They’re operating from a place of fear. But if you spiritually understand that everybody has something of value, that everything is a shift in movement of energy, that you’re in the hand of God, your heart, eyes and ears are open. Then when things happen, you can respond to them and you don’t have to feel like the bullseye is somehow this set target that has to be driven into in such a specific way that you’ll find it there. Anybody who is in the fight world knows this is how it works. Anybody from the military knows this is how it works. Anybody who’s doing medicine knows that you don’t know until you cut the body open that you’ll figure it out. You have the tools, you’ve done the work and you hope that it’s gonna end in a successful way, but it is not your time and it’s not your world. You just have to be present, observe, listen and respond. This is such a great question. Now that you’ve asked it, I’m surprised nobody’s ever asked me this before.

All the uncertainties that come with making movies and the film business at large feel far less confrontational under those terms: things are gonna play out the way they’re gonna play out.

Of course. And you know what? There’s always somebody doing better and there’s always somebody doing worse. If you think that Christian Bale isn’t frustrated about career things from time to time, you don’t know the acting business. There’s somebody trying to be a background artist on an off-Broadway show who’s frustrated that they can’t get a certain opportunity and would kill to have this other person’s opportunity. We’re all doing our best and you work as hard as you can, but you also have to take into account how blessed you are. I got two arms, two legs. I have healthy children and a healthy wife. My parents are alive. I live in America. There’s a hospital right down the street. I got running water. There are incredible actors out there whose movies just haven’t hit for them. Then there are other actors who got that shot because they were on a show that happened to pop. So there’s a bit of luck involved, too. It has definitely made it easier for me, particularly in the past few years. I’m comfortable with the lulls. I’m comfortable being uncomfortable, you know? And I think it takes time to get that way. Sometimes you’re the dude who’s promoting a movie, doing the interviews, doing the photoshoots, talking about magazine covers on talk shows, and then, like every actor pretty much, you’re not opening a movie or premiering a TV show or doing those kinds of activities. One might think, if they didn’t have a sense of spiritual connection, that their self-worth or their value is somehow diminished by this. Not everybody’s always doing everything all the time. We’re in flow, man. We’re just figuring it out. And sometimes, I think you do have to vocalize how your self-worth and your talent is not connected to these outside forces because we are susceptible to it. There’s always the nagging feeling, a noise that can start like a dog whistle that becomes very, very loud. I think people are particularly susceptible to mental health issues in this business because the highs can be so high and the lows can be long and quiet. But if you know that you’re in the hand of God and you’re gonna work your ass off, it does provide a sense of comfort: knowing that, as long as you keep working hard, the employment will come.

And you do have some control, especially at the level you’re working at, right? You can say no to things, you make choices, you can take the lulls, as you say. I saw that you wrapped on the Nick Cassavetes movie, God Is a Bullet. What’s next? What have you been looking at?

Well, I love television. I’d love to find another real home with a character, in a world that I can go deeply into for a few years. I’m developing something with some of the folks from Kingdom, which is lovely. It’s about a totally different world. I’d love for that to come together, but those things just take a while. I’m so grateful that my intuition has proven right about Jamie and about Cassavetes, who is also somebody I hope to work with for the rest of my life. It kind of reinvigorated my love of film. I had no interest in doing independent movies before Jamie’s movie because I had done so many of them earlier on, ten years ago. It’s just that you work so hard and there’s no guarantee of distribution. That’s challenging. You wanna know that people are gonna see your work at a certain point. I know you’re always rolling the dice, but on TV, you have a net: the pilot can be okay, but you can make it better, or a season can be great and the next one’s not as great, but that’s okay, you can reconfigure and always kind of play catch-up. With films, you really gotta thread the needle. But I’m more comfortable at this point with movies than I have ever been.

You’ve also spoken about a dream project: a love story set against the Opium Wars. When you were asked that question, there was no hesitation like the idea lives in your back pocket.

I love that world. My kids speak Chinese. I took Chinese in high school. I love that time period. I love that dynamic. I would love to put that together. But the project I’m developing now in the TV world is probably my real dream project. I like going deep into worlds and we don’t always have that opportunity. You’ll be the first one I tell if we’re able to pull it off. Truly, I’ll give you a call.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments

Comments are closed.