I just want to be remembered as an actor who was a lucky man.

Whether you know him by name or by face alone—you know, “that guy from that thing!” sort of recollection—Udo Kier remains the wildly Teutonic character actor who’s nearing 300 credits to his name in a storied career that spans more than half a century. His presence—both on and off the screen as we’ve come to discover at Anthem—is undeniable. In cinema, he leaves an indelible trail of some truly gonzo performances and collaborations with some of our choicest auteurs: Lars von Trier, Gus Van Sant, Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders, and Dario Argento among them. Now in his mid-70’s, Kier scrapes the skies again in Todd Stephens’ Swan Song: Slaloming to the needle-drop of Robyn’s “Dancing on My Own” as a crystal chandelier headpiece short-circuits on his dang head; cruising down a desert road in an electric wheelchair, all resplendent in his mint-green pantsuit and fedora. You’d think this was impossible: We’ve never seen him quite like this before.

An unlikely journey of an older man, Swan Song’s narrative spin springs to mind David Lynch’s The Straight Story—except there’s nothing “straight” about it. Kier plays Mister Pat, aka Pat Pitsenbarger, a real-life personality from Stephens’ youth and hometown of Sandusky, Ohio. At one time known as the “Liberace of Sandusky,” Mister Pat had worked his hairdressing magic on wealthy socialites and moonlit as a drag performer. A man of flamboyant renown in a tiny hamlet.

When we meet Mister Pat, he’s already been reduced to an assisted living facility, waiting for oblivion. He spends his days obsessively folding cafeteria napkins and dozing off in his recliner. Then, he receives an unexpected visit from a probate lawyer with a bizarre request. His one-time client, Rita (Linda Evans), has passed on and stipulated in her will that Pat style her cadaver in exchange for twenty-five thousand dollars. Having fallen out with her many years ago, Pat initially declines the offer, but then quickly comes around to the idea of burying the hatchet, fulfilling her final wish, and reanimating his long-dormant passion. What follows is the most uneventful escape in the history of “prison” breaks. Flying the coop, Pat confronts long-buried resentments—exchanging barbs with the likes of former employee-turned-rival Dee Dee (Jennifer Coolidge)—and comes to terms with a place he barely recognizes anymore. In the end, the imperious elderly diva gets the send off he deserves. But not without the unbearable sadness of watching a giant come to a dawning realization: What once was can no longer be. And that’s okay. That is just life.

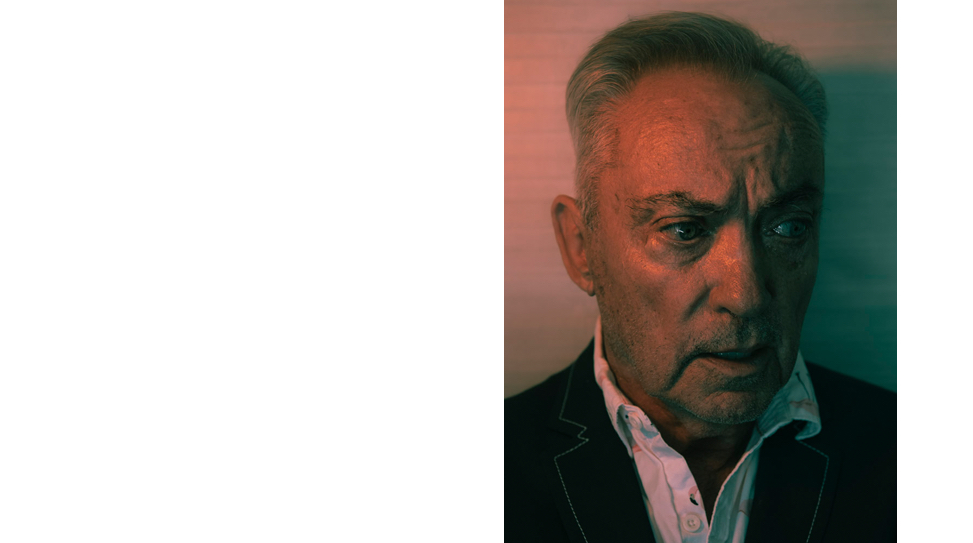

Anthem reunited with Kier at LA’s W Hotel for an in-depth conversation and exclusive photoshoot.

Swan Song opens in select theaters today, and goes On Demand on August 13.

[Editor’s Note: The following interview has been condensed for length and clarity.]

How did the screening go last night? I know the theatrical experience is important to you.

We had a good time. I like the film and I’m very happy for Todd [Stephens]. I just saw him for lunch. We’re both very happy with the result. I was happy to see Linda Evans again. When she was talking onstage about the film, she was very sad. So was I. It’s amazing that this film really takes you in. Even though it’s me on the screen, it still gives me the feeling of sadness. This old man is dancing with a chandelier on his head, singing [Udo breaks into song]: “I’m in the corner/Watching you kiss her/Why can’t you see me?” We had another screening at a university and there were very young girls—18, 20—and after the Q&A, they said how much they liked the movie. One of the best movies they’ve seen they said. But for me, of course, the biggest surprise after making movies for fifty years is to read the critics say, “Finally, Udo Kier becomes a leading man.” I couldn’t believe it, but I understand why. With Lars von Trier and Gus Van Sant—all the films that I’ve made with really wonderful, strong directors—I always had a supporting part. In Swan Song, you follow the character from beginning to end. He’s a special character—you’ve seen the movie. The moment he puts the green suit on, he knows he will never take it off. He will even die in that suit. In the cemetery, you see him cry for his dead friend. The movie is sadness and opulence. It’s strange sometimes, but it makes you interested. So I understood why they would say that.

You beat me to it. Because you’ve had leading roles prior to this.

In ’73, I was Frankenstein. I was Dracula. They were leading roles. But since 30 years ago, after coming to America, it was always Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, Blade, For Love or Money—all supporting in a way. Even in newer films like Downsizing, it’s a very nice role, but people always concentrate of course on the main parts. That’s a logical thing.

You’ve also been getting some of the best notices of your career. Has that surprised you?

Well, I am proud. It’s wonderful to get such good reviews about the film and for my performance. I told my manager that I should now get work as a leading man. I cannot go back to playing one or two days and go back to what you’ve known me for. So that’s the idea for finding new characters. I’m looking forward to finding one or two films immediately, or soon, where I’m the leading man again. Also, I think there’s a big chance of finding a movie that I liked when I was young to remake it. Something like that. I got many scripts from Alejandro Jodorowsky a long time ago because I was supposed to be in Dune. And then he didn’t do Dune—David Lynch did it. Then, of course, somebody else played my part. Sting, actually. Feyd-Rautha was the part. I like Jodorowsky. There’s a lot of nice directors like him. There are good directors like [Pedro] Almodóvar and Wes Anderson. I love Terrence Malick—his movies are so different.

In discussing your method over the years, you’ve often gone back to what Lars von Trier once said to you, which you prescribe to: “Don’t act.” That sounds easier said than done.

That is one moment I will never forget. It was when we did Dogville, when we were all at the same table. Everybody was treated the same: Lauren Bacall, Ben Gazzara, James Caan, Nicole Kidman, Chloë Sevigny, Stellan Skarsgård, and me—Udo Kier. Lars looked at us while we were eating and said, “And don’t forget: Don’t act.” As an actor, you’re a star, so of course you act. What he meant was, don’t act as though you can feel you’re acting. There’s a lot of famous actors who will start with their backs to the camera, by the chimney. Then they turn around and they will speak to the floor. And then, finally, they will speak to the actor opposite them. [laughs] And that’s not acting.

With this film, I said to Todd, “I would like to shoot almost chronologically.” And we did. I also said, “I want to be in the retirement home a day or two on my own without a camera.” I wanted to sit by the window and look out. I wanted to fold my little napkins. I wanted to lie on the bed. I wanted to look in every drawer so that I knew it’s my room and I’ve been there for years. I cannot treat it as a film set, coming out and saying, “Okay, let’s shoot.” So that was helpful. At the cemetery, I said, “I don’t want to see the gravestone. I don’t want to see anything. I’ll just be near. Give me a sign and I will come forward.” And I did. The whole film was like that. We were very lucky that Sandusky is one street. I mean, there are more streets of course, but there is one main street with the secondhand shop, the theater—everything was on that street. The street was not very long. It became basically the set. After I would finish shooting every day, I went with my green suit to the bar and they said, “Hi, Pat. Chardonnay?” [laughs] That’s how they knew me from shooting on the street. I had an amazing time. I was happy that we had an amazing collaboration. If I could do the film again, I wouldn’t change anything. I would leave it just as it is. I liked the green suit. I couldn’t imagine wearing anything else after putting it on.

When you were at that retirement home taking in the surroundings, did you also imagine what it would be like to live there yourself? I wonder if such a place could contain you.

I didn’t think about me. I felt that I forgot I was Udo Kier. I was of course thinking about the past: the period when [Mister Pat] was famous in Sandusky. It was a great time. David Bowie. Elton John. I was smoking More cigarettes. I’m not a smoker anymore, for many years. But I couldn’t fake it so I smoked. Of course I never met [Mister Pat] and didn’t know of him, but when I got to Sandusky, Todd introduced me to some of his best friends—elderly gentlemen—and I talked to them for a long time. They showed me how he smoked, how he talked, and the movements of his body. I did my research only with the friends because they knew him better than anybody else.

Did you find Mister Pat and his life experience relatable?

To my life? No. It was about seeing the city, talking to his friends, and being in the salon he once had. Of course, his store is not his store anymore so there were different things I had to accept. The city is different now so I saw pictures of how it was before. It was about observing all the time. I went down memory lane. It was a combination of many things.

I understand that Todd flew out to Palm Springs to meet with you after you read the script. What are you looking for in that kind of scenario with a potential future collaborator?

First of all, I hadn’t seen any of Todd’s previous movies. I wanted to meet him in my house, in my own environment, to see how he talks about art. I have a lot of art on the walls. I wanted to meet him to see if I like him because I’d have to work with him. It was important to see his ideas about books—about everything. Also, we talked about the script and agreed that we shouldn’t get too crazy, too flamboyant, and all these kinds of things. He told me he liked to rehearse on his other movies. But we didn’t rehearse—almost. That’s how the film was basically done. Having done however many films—the internet knows more than I do—I didn’t feel like I was making a movie.

Mister Pat left behind a legacy and the making of this film is one proof of that. Your legacy I can’t even begin to wrap my head around. How do you want people to remember you?

I just want to be remembered as an actor who was a lucky man. I mean, I sit in an airplane, from Rome to Munich, and next to me is an American who says to me, “What do you do for a living?” I said, “I’m an actor.” Right away, with my two fingers, I got a picture of myself in front of his face. He says, “Interesting. Give me your number.” And I said, “Who are you?” He says, “I’m Paul Morrissey. I work for Andy Warhol.” A couple of weeks later, I got a call: “Hey, it’s Paul! From New York! Remember the man from the plane? I’m doing a film in Rome for Carlo Ponti, the husband of Sophia Loren. I have a little role for you!” I said, “Wow. Thank you very much.” [laughs] I said, “Who do I play?” He says, “Frankenstein.” So everything in my life is like that.

I go to Berlin and a young man comes to me: “Hello. My name is Gus Van Sant. I have a little movie here called Mala Noche. I made it for twenty thousand dollars. But my next film will be with Keanu Reeves and River Phoenix, and I want you to be in the movie.” He got me a work permit and everything. Thanks to him, I came to America with My Own Private Idaho. Thirty years later, I’m here talking to you. With Lars von Trier, I saw his movie, The Element of Crime, at Mannheim [Heidelberg], which is an intellectual film festival where I was also an invited guest. I really loved it. There were these American directors and I said to them, “Well, we can all go home because whoever made that film is going to win the prize.” They said, “You think so?” I said, “Yes.” And Lars won. I went to the festival director and said, “There is one person I would like to meet: Lars von Trier.” I expected somebody like [Rainer Werner] Fassbinder dressed in black or [Stanley] Kubrick in a bad mood. But here comes this young man—Lars. We had a beer and exchanged numbers. After a few weeks, he called me and said, “Hi, Udo. It’s Lars from Denmark. I’m making a film called Medea. It’s a script by Carl Theodor Dreyer. I want you to play the husband of Medea, King Jason. But there’s a problem.” I said, “What is the problem?” He said, “You don’t look like a viking. Please don’t shave anymore. Don’t wash your hair for a couple of weeks. Come in four weeks because I have to sell you as a viking.” So I looked a bit strange, but after four weeks, I went to Denmark and got the part. That was the beginning of our friendship. I became right away the godfather to his first newborn. We did ten films together over the years. I just finished with Lars four weeks ago on the last episode of The Kingdom. The number one reason I wanted to do The Kingdom is because I would be the only actor in the history of cinema to be born on screen. I had to be on this bed with this model of a woman, in the stomach. I pushed myself coming out and I just went [Udo lets out an unsettling guttural sound] with all the blood and slime. So basically, Kee, that is my life. I’m a lucky man. I’ve never asked a director to be in their movie. There are some directors I would like to work with, but I only tell them the truth: “I like your movies.” Let’s see what the future brings. There have been some screenings and press people have seen [Swan Song], and they all seem to like it. So let’s see. I don’t know.

How did you celebrate Udo Kier Day in Palm Springs this year?

On Udo Kier Day, I was with a good friend of mine, Ron Oliver. He’s a film director. He’s a neighbor who lives two minutes away from me. He took me to lunch and then we had a little drink by my star. I don’t really know what it means for the city to declare a Udo Kier Day. Maybe I go into a store and get everything for free. I don’t know! [laughs] Maybe at Applebee’s or some sushi place? I love sushi. I’m a big, big sushi fan. But only tuna—albacore. So I didn’t do much. Now, I will focus on what’s coming next. I made a film that’s coming out soon called My Neighbor, Adolf. It’s an Israeli production with Poland. I made a film called The Blazing World with Carlson Young. She actually came to the premiere yesterday. She’s a wonderful, strong girl. Very beautiful and a good director and a good actress. That’s the only film I did last year in America. We shot on a farm in Texas, under total security. Nobody was allowed to leave so I felt very safe. As I said, I worked with Lars on The Kingdom this year. I did a film in Colombia that my neighbor Ron Oliver shot at the beginning of last year. When I came back home, people started wearing masks.

You once told me you like to play characters people will remember. That hasn’t changed. When I look back on Swan Song, I think I will most remember that chandelier on your head.

Yes, I think that’s also the same for me. I knew I would have to wear the chandelier, but I didn’t know that it would be lit. When it came to the day, with all the electricity around my neck, I was a little bit reluctant. But the scene works. Because I fall down and now I’m in the hospital. I wake up and I go get my green suit and I’m leaving the hospital, saying to the doctor, “I’m late to my funeral.” I’m happy that you liked the film. I’m very, very, very happy that people liked the film—and not only people but that the critics liked it. It’s also important that it’s generational. In Germany, I was in a group with Fassbinder’s people and some died of AIDS. Now people take one pill and they’re undetectable. You see, time has changed in every way. If you said twenty years ago, “In America, gay men will get married and adopt children,” they would’ve said, “You’re crazy. It will never happen.” But it did happen. That’s a good thing. Swan Song is about that. He sees that now, if people like each other, anyone can hold hands at Applebee’s or McDonald’s. [laughs] Nobody cares. But twenty years ago? They would be thrown out the back. This film has much more to say every time I see it. I will see the film again tonight. These are messages, but not with the finger: “Don’t do that!” It smoothly goes. It flows. It’s also funny. That’s all I can say.

Clarion Call: Garrett Hedlund

Clarion Call: Garrett Hedlund A Conversation with Simon Baker

A Conversation with Simon Baker

No Comments

Comments are closed.