In the end, existence is nothing but a shared experience of loneliness.

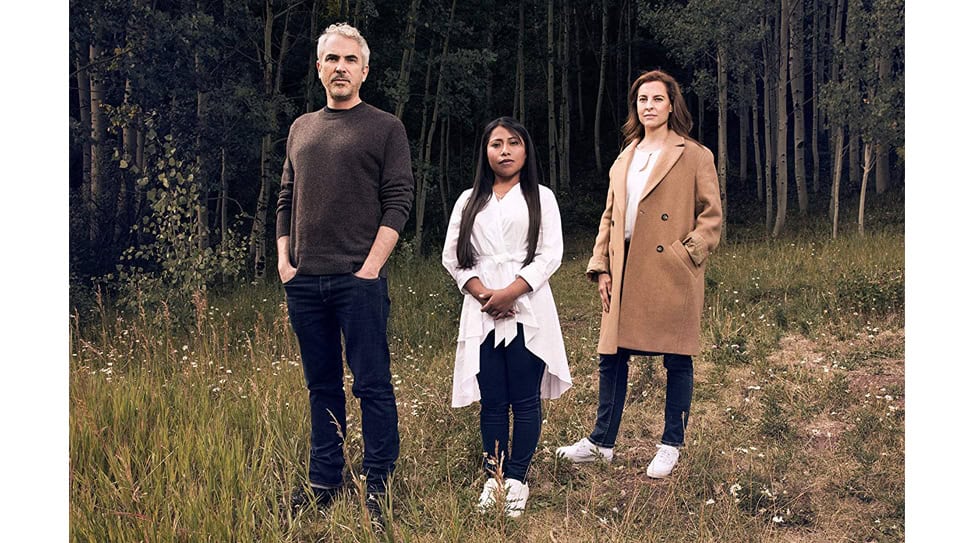

Roma marks Alfonso Cuarón’s first film in his native Mexico since Y Tu Mamá También (2001). Cuarón not only directed, produced, and wrote Roma, he shot it as well—after Emmanuel Lubezki dropped out due to a scheduling conflict—in majestic 65mm black-and-white cinematography. The film has received consistent, extravagant praise since premiering at the Venice Film Festival.

The film is a personal one for Cuarón in so many ways. Roma shares its name with a neighborhood in Mexico City where the director grew up. Its central character is a stand-in for Libo, the woman who helped raise him in the early 1970s and to whom he dedicates the film. We follow approximately one year in the life of our protagonist, Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio), a domestic worker of Mixteco heritage for a well-to-do, middle-class white family comprised of patriarch Doctor Antonio (Fernando Grediaga), his wife Sofía (Marina de Tavira), and their four children—one who’s presumably based on Cuarón himself. Cleo has a comfortable routine as an extended member of the family, and do to life’s often cruel advances, her world begins to unravel in tandem with that of her employers. Much of the film is episodic and observational. It’s also told on an epic scale, and as a result, more a portrait of a time and a place than of a specific character.

The subject of the movie isn’t so much about class contrast. Instead, it’s about the way in which individual lives play out in quotidian ways against the backdrop of much bigger happenings. A series of catastrophes slowly upend the stability of this world, starting with a business trip Doctor Antonio takes that proves life-altering for the family unit. There’s also an earthquake, an unexpected pregnancy, whispered conversations about land grabs, and fires that mysteriously appear on a wealthy hacienda during Christmas. In one astonishing sequence, Cleo and the family’s grandmother watch as a student demonstration turns into a police riot on the streets, an incident known as the Corpus Christi Massacre of 1971, which Cuarón doesn’t explicitly identify as such. Roma is that rare movie that’s in no hurry to reveal what it’s about and it would be much too revealing to describe further in detail how these events mesh with Cleo’s own world.

Every scene, character, and shot has been nurtured with loving care. Roma is one of the most lovingly and painstakingly crafted cinematic tributes to any one person in recent memory. It’s also a defining moment in Cuarón’s already remarkable career.

This movie has been on your agenda for some time. When did it really start taking shape?

Alfonso Cuarón: Yeah, I guess it’s been gestating for a long, long time. The first time that I had a conscious impulse to do it was actually 12 years ago. I thought it would be my next film after Children of Men, but that didn’t happen because of life and I think it was for the best. I do think I had the tools—the resources—to make it, but it wasn’t so much about that. I still needed the emotional tools to make it.

When you say “emotional tools,” what are you referring to exactly?

Alfonso: It was not by choice. I didn’t feel secure enough at that moment maybe. After I start drafting something, I let it go. When I say I didn’t have the tools, on the one hand, I probably didn’t have the confidence in terms of letting go because a lot of this process is about—for all of us—not having safety nets. On the other hand, it was about the tools in terms of approaching some stuff in my personal life or the people very close to me in a completely naked way.

Marina—I can imagine Roma was probably a different experience from your other shoots.

Marina de Tavira: Yes, it was absolutely different from all other experiences I’ve had as an actress. The first thing I would say is that we were working without a script. Alfonso had it, but we didn’t so he would deliver the information about what was gonna happen day by day and separately to each actor. Then he would put it together, and magic and life would start to appear. For me in the beginning, it was really hard because I had to work in a different way—backwards. As actors, we tend to first understand the character and analyze the situation, but there was none of this. It was like life and how life surprises you. In life, you don’t think about something until it happens. So that was the process, just like in life.

Alfonso: We shot in absolutely chronological order so they were learning day by day what was going on. As in life, they didn’t know what would happen the next day.

Yalitza—how was your experience on your first film in this debut acting role?

Yalitza Aparicio: Yes, it was my first experience. It was complicated. During the shoot, I tried to forget that I was in a film and tried to see it as real life. In life, there’s nothing written. Since Alfonso didn’t give us a screenplay, this is how I tried to see it: living it like it was my own life.

Alfonso: I have to add that it’s very admirable what Yalitza and Marina did. On the one hand, Marina really had to unlearn because she was facing chaos all the time. I would give directions to each actor individually. I would also give them written pages—the dialogue—that same morning so Marina would have certain expectations about what was going to happen. But the instructions to the other actors would completely contradict everything that was written down so Marina was always trying to catch up to the situation. The funny thing is that, with Yalitza, she thought this was the normal process of making a film. By the same token, it’s marvelous because she would receive the pages and a lot of the dialogue would be in Mixteco and she’s not fluent in Mixteco. Nancy [García], who plays Adela, is fluent. Yalitza would have to master Mixteco every day.

Wow. Could you talk about the role that nature plays in the film? You take us through the earthquake, the fire, the ocean…

Alfonso: You rightly say that there are a lot of elements. We tried to honor fire, wind, water, and earth. At the same time, we tried to also acknowledge stuff like heaven and earth. The film starts by looking at earth in which heaven is nothing but a reflection through the water. Eventually, the water starts to take on a more meaningful role and everybody’s submerged in water. It finishes with us looking up at the sky for the first time. Part of what that’s saying is that life is transient, you know? It also has to do with our individual experiences. There are elements that are completely out of our control. Our relationships and affections are the only things that we can control and flow through. There’s also a randomness, not in those affections, but in those relationships. In the end, existence is nothing but a shared experience of loneliness.

How did you conceive the sound design? It gives a complexity to the surrounding world in every single moment.

Alfonso: Memory was a tool of research for this film. The tool for diving into this film was memory. It was about reproducing spaces or recovering spaces. It was about casting doppelgängers to stand in for people from real life. The costumes have to reflect reality. We wanted to shoot the same streets with the same cars parked in the same neighborhoods, and so on. But those visuals are just one single aspect. Probably in many ways, the visuals are the less important aspect. It’s a cliché to say that Proust wrote through smells and tastes, but at least in my experience, that is true. The other thing is sound. Proust doesn’t—well, that’s not true, he talks about bells of the church, blah blah blah. I would know if I was doing a scene and it was making sense because it was not only about what I was experiencing there. What I was looking at and what I was listening to was obviously subjective because my sense of smell would trigger memories. I wanted to recreate memories in the same way using sound. It’s the sound of the city and the sound of a society. Each society and each culture has its own musical rhythm, and it’s not focused. It’s all around us. It’s acknowledging what we’re talking about: the elements of earthquakes or wind that we can’t control are around us. The goal was not to give answers or telegraph things to the audience because the narrative is very objective—it’s not a subjective point of view. We want to create a very individual experience for the audience. We want the audience to be participants in experiencing it through their own memories.

You seem very inspired by the experiential nature of it, perhaps more so than the storytelling.

Alfonso: The process of making this film was never an intellectual one. It was about gathering from my memory and my endless conversations with Libo, who Cleo is based upon. It was about merging my memories with her memories, making sure that a big percentage of that were shared memories. Some stuff, like Libo’s personal life outside of the house, I couldn’t know and it was what she would describe to me. For example, the scene with her doing exercise every night with a candle because the grandmother would be upset if she wasted electricity. Everything is precipitated from the prism of my present self, but it was never an intellectual choice. The funny thing is, I was doing a film about Cleo in which the family was this satellite thing around her. It’s just what happened. It was not by design that there were other circumstances that includes Sofia, that it’s a period of my story when my father left, and that it’s when the father of Cleo’s child also left. It was never an attempt to make a statement of any kind. I hope that the film is not telegraphing or trying to make a statement. Again, it’s like life. I hope that it’s something the audience partakes in through the prism of their own experiences, rather than something that they’re just receiving.

How did you end up calling this film Roma?

Alfonso: Roma is the neighborhood where the story takes place. It was untitled when we began and the funny thing is that my producer, Nicolás [Celis], used Roma as a work-in-progress name when he needed to get permits. It’s called Roma because it takes place in “Colonia Roma.” It just stuck. But I can see how you could pull metaphors and that’s okay. It’s like the rest of the film: everyone will make their own interpretations.

It was fun to see a clip of John Sturges’ Marooned in the film as a sort of nod to Gravity.

Alfonso: It’s the opposite! Gravity is a comment on Marooned, not the other way around. [Laughs] I watched Marooned precisely around that period when the story takes place. I guess I like this idea of drifting into the void. It’s something I remember as a kid and what I was talking about: a shared feeling of loneliness. We’re like these astronauts. The only thing that keeps us going is that human connection. And isn’t it great that I can say I had Gene Hackman in my film? [Laughs] Sorry, the first one billed on this film aren’t Yalitza and Marina—it’s Gene Hackman.

How did you approach your role as the cinematographer? You haven’t done that in a while.

Alfonso: Well, the approach is not like with sound. I was clear about wanting an objective experience and I wanted to honor the sense of time—not only the passage of time throughout the film, but the sense of time itself. When Cleo is washing the floors at the beginning, it takes its time. She even goes to the bathroom and we just wait for her there, you know? That sense of existence and how things flow in time was important to me. It was as much about honoring time as honoring space. The thing about time and space is that they obviously limit us. They limit what we are and, at the same time, create opportunities for visual experiments. There’s also the social experiment that goes along with it because it was this whole thing about not giving more weight to the characters than the environment. When we’re surrounded by people, it’s obviously a social environment. But when we’re in nature, nature is also part of that universe and it’s informing us all the time. For me at least, memories also work like that. Memories are colored by the universe around you. That’s the reason why, as much as possible, we wanted to honor that idea. It was also for the actors because the whole thing was so fluid. They needed a space of action. If everything is shot very wide, that would allow them to be flowing around the frame if anything happened in the scene. In some instances, they were going out of the frame and then coming back. The thing is, Chivo [Emmanuel Lubezki] was originally going to do it. His DNA is still all around.

Yalitza and Marina—what were your impressions of seeing the finished film?

Yalitza: The first time I saw the film was at Venice and we were together, Marina and I. At the end of it, we were crying. We felt the excitement of seeing all the hard work that was put into it. Also, with Alfonso there, it was amazing. I was told during the making of the film that there would be some scenes that would not make it into the film and that happened, too, but I think the way he put it all together was just fabulous.

Marina: Yes, it was incredible. Everything that I think about the movie came after it was done because when we were doing it, it was just about swimming into the experience and not thinking and not rationalizing anything. Then when I saw it, all these thoughts about being a mother, about my lost childhood, about my father who also left, and about me living with my kid alone started to unfold and arouse and it was really moving. It still is.

Alfonso: This is a film about the past, around ’71. I want to say that what the audience is feeling is exactly what Marina is saying. They invest their own experiences into the film. I heard the same thing from someone from Italy and from Bombay. They told me that it was just like that for them there. And this film is black and white, but it’s not nostalgic black and white. It’s the past seen through the present. It’s digital 65mm black and white without grain, you know? It’s almost sacrilegious if you consider classic black and white, which I enjoy by the way. We just didn’t want it to feel like we’re immersing into the past. It’s a point of view from the present. It has to be from the audience’s own standpoint. Marina will have her experience. Yalitza will have her own experience. In the same manner, hopefully, the audience will have their own as well.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

5 Comments