Hiding your feelings is much more cinematic sometimes than the feelings that are demonstrated.

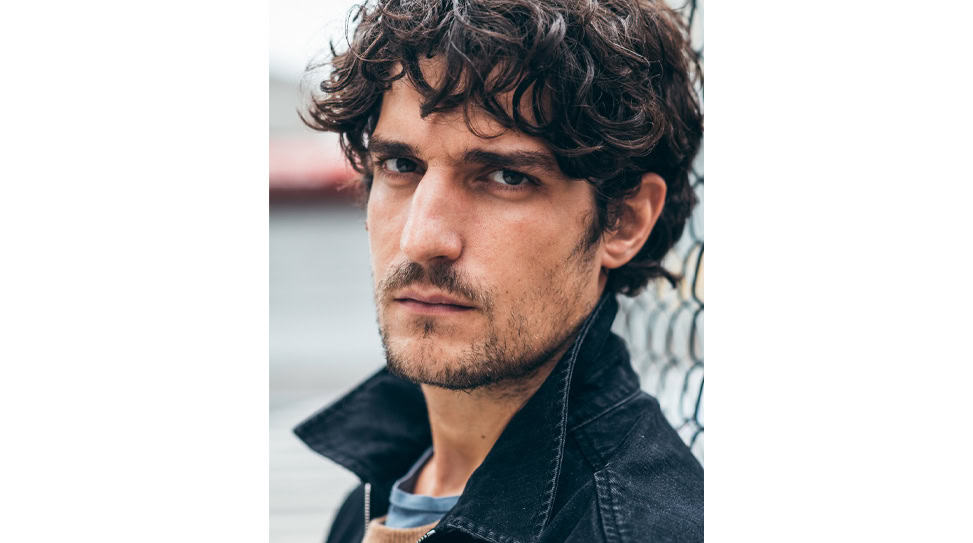

It’s rather remarkable to look back and realize that, at age 35, Louis Garrel has already worked with the best of them: Bernardo Bertolucci, Christophe Honoré, François Ozon, Jacques Doillon, Arnaud Desplechin, Michel Hazanavicius—not to mention his iconic father, Philippe, on numerous occasions. Next up for Garrel on the acting front are Greta Gerwig’s much-anticipated reboot of Little Women and his headlining role in Roman Polanski’s already controversial J’accuse.

Garrel—our perennial, French “It” man—realized a long-standing dream on his sophomore directorial feature A Faithful Man: working with venerated novelist and screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière. The co-written effort—his follow-up to 2015’s Two Friends, also co-written, that time by his long-time collaborator Honoré—examines Abel (Garrel), a lovelorn journalist, who’s blinded-sided by his girlfriend of three years, Marianne (Laetitia Casta), who breaks the news that, not only is she pregnant, but the father of the baby is their best friend. In the film’s deadpan opening, Abel takes it on the chin and cooly walks out of their shared apartment and out of her life. Cut to nearly a decade later, we see Marianne’s eventual return into his life following her lover’s unexplained passing in his sleep, much to the chagrin of Joseph (Joseph Engel), her 9-year-old son, as well as the resurfacing of her sister-in-law, Eve (Lily-Rose Depp), who has harbored a crush on Abel for most of her young life. “It’s about sex and death, and broken friendships,” Garrel allows. “In general, it’s a French movie.” He’s not wrong. This movie is about as French as movies get.

This new series, Culture Marker, is Garrel’s third sit-down with Anthem, after our first meeting at Cannes to discuss his debut feature and another to unpack his acting effort in Maïwenn’s The King.

The 56th New York Film Festival ran from September 28 to October 14.

The last time we spoke in 2015, you didn’t have another directorial feature in the works. When did A Faithful Man start coming together as a concept?

It started two years ago. I’m close friends with Jean-Claude Carrière. I’m a complete admirer of his work. So I started to ask him: “Do you want to try to write something with me—without any producers?” I didn’t want to have a producer at that point in the process. He said, “Yes, okay.” We worked like this, step by step. I gave him ideas. We didn’t know exactly where we were going with it. We didn’t have a structure—it was an improvisation movie. Then after a year, I came to a producer and said, “Let’s do it right now.” So we did it then. We came to the producer in November of last year and shot it in February and right now we’re at festivals.

Was working with Jean-Claude as rewarding as you had imagined?

Yes, because he has a sense of “the game.” He knows how to play with the audience. The story starts in Paris with two women, a man, and a kid—it sounds familiar for the audience, especially for those who love French cinema. So when you start the movie, you have to understand that the audience is super quick and they have expectations. Jean-Claude has to make a surprise about that expectation. This is something I learned from him. You ask yourself, “What are we supposed to see after that scene, normally?” Then we have to do a completely different scene. Also, we tried to make the character believable, even if there are moments where we wonder, “Are you sure?” when we’re writing the script. “Are you sure about that?” I think my character is a little bit like a clown because he accepts difficult things without any complaint. It’s a bit similar to the mechanics of a clown. Then there’s also the thriller genre with the kid fooling everybody. People call this movie a romantic comedy, but you can’t exactly describe the movie like that—not totally. There’s also a part of the movie that’s a gag movie. We tried to mix different genres like this, you know? In this way, you can also give existential ideas about how we hide our own thoughts in real life. For example, sometimes we think that we have a feeling about a situation, but really, there are no feelings. The feeling becomes talking about it, you know? There are no pre-feelings—the talk is the start of our feelings. That’s the reason I took from [Pierre de] Marivaux, the French writer. Take someone who’s not in love with you, for example. There’s nothing about you. I tell you: “You know, that guy in front of you—I think he loves you.” What do you mean you think he loves me? “No, no. He’s crazy about somebody close to him.” Who? “Somebody very beautiful that he sees every day. It’s not you.” Then you create the disappointment. You, who didn’t even think about being loved before this—that desire is taken away from you. The movie is a little bit about that. You create a disappointment. You don’t actually have that feeling—you create that feeling and try to understand what that feeling is. I know it’s a little bit confusing, but it’s something like this.

It’s like Buster Keaton what you’re talking about.

Yeah! Buster Keaton—somebody can hit him, but he never complains. He just looks at what’s fallen on his head. He never thinks, “Who did that?” This is why we like Buster Keaton. We empathize with him. It’s also what gives him his power. He can move past all those events without any kind of pain. He’s disconnected in that sense. He has his own way of thinking.

It’s exactly the opening scene of A Faithful Man. Abel reacts in a way that we don’t expect.

Normally, in the conventional situation when a guy is treated like this, he’s going to get angry. But Abel chooses not to be angry. What can that change, you know? If he screams, it will change nothing. So I think it’s actually more real in that kind of situation. This kind of attitude is more real than that other, conventional fiction. That’s where I’m at.

I almost see your two films as companions. You once described Two Friends in this way: a feminine movie about the friendship between two men—two losers that are so attached to their feelings. A Faithful Man is the absence of feelings. They don’t talk about their emotions.

Exactly! Two Friends is about passionate characters that show that they’re in love. It’s crazy and fever-like. They’re attached to being in love. They’re feeling painful about the way someone’s not looking at them. They’re pretending to be in pain. So this film is completely different. All the feelings are hidden. Even the characters are hiding them. They don’t even understand what they feel. They feel like real life because they don’t even want to show their feelings. This is what I like to watch about them. I think sometimes it’s the opposite about what they say. Hiding your feelings is much more cinematic sometimes than the feelings that are demonstrated.

You seem quite attracted to starting from a place of theater. A Faithful Man originated from the writings of Marivaux. Two Friends was based on the play The Moods of Marianne.

Yes, Carrière and Honoré took their main arguments from plays. When one friend is complaining that a woman is not in love with him and the friend who is trying to help him falls in love with her—that’s Jean Renoir’s La règle du jeu. It’s The Rules of the Game, I think, in English. When you take an argument from a classic French writer, you are in your country. This is also always about working with material that’s French: it’s all about feelings. The culture is about French writers like Olivier Assayas and Marivaux—the words are so much about feelings and how sometimes it can be violent to be in love and not what you expect. It’s a very French way of describing things, you know? Shakespeare, for example, is about treason, power, and healing. It’s much more difficult in France because we don’t have that background. We don’t have a cultural background of explaining that on stage. So sometimes it’s good that cinema is completely different than theater. We have a cinematic way of telling stories. But I like to be connected to the dialogue of theater—the theater expression. I like this idea of structuring where you grab the attention of the audience with the first scene. This is what we tried to do with A Faithful Man.

Something struck me at Cannes. You said it was “orgasmic” to hear the audience laugh at Two Friends. You had spent a lot of time writing those scenes, being as specific to say: “I want people to laugh here.” Did you have a similar writing experience on A Faithful Man?

I’m much more surprised because I wasn’t thinking about the laughter while writing this film. Yesterday, the people were laughing a lot so I was super surprised. I didn’t expect that. It’s also the pleasure of being at festivals outside of your own country. It’s because you understand, despite having different ideas about morals and love and everything. At Toronto, there was this person who asked me: “Is this how it is in France? A man goes from one bed to another bed in a different apartment?” I can tell him it is, if I want to promote my own country… [Laughs] The sense of humor was very important for me, to make a comic situation that will be understood in different countries. If it’s local—if the love is just national—I don’t like that.

You’re looking for transcending moments.

Exactly. When we talk to somebody that we don’t know from a different country, most of the time, you try to connect with your sense of humor. Your sense of humor is something you can use to connect with a stranger about who you are and what your level of appreciation is about things. I love senses of humor, in general. With Two Friends, I was super excited about hearing people laughing. I was super excited that they laughed a lot. Jean-Claude also taught me a lot of things about writing some scenes on A Faithful Man because I would think, “People won’t understand that joke,” but then it would turn out so perfect. I would watch the scene and they’re so perfect. The writing was super good and I would see that Jean-Claude was right.

You told me that shooting Two Friends was sometimes stressful. How did this one compare?

It was very different because we shot A Faithful Man in four weeks. It was super quick.

You also had rehearsals, right?

We had a lot rehearsals with Laetitia [Casta] and Lily-Rose [Depp] because they had their own feelings about the characters and the story. I had to find some surprising ideas about how we can do the scenes. I also rehearsed a lot with them so we could make the movie quickly. I was super proud of making the movie in four weeks, but then I realized that Luis Buñuel makes his Mexican films in 18 days. Brilliant directors make films so quickly sometimes. The more you prepare, the more you want exactly what you have in your head. I wanted to make a short film, an hour and 10 or 15 minutes. I knew that from the beginning: “This story needs a short period of telling.” I knew precisely how much time because I made a mistake on my first movie, in my opinion. The exposition was 17 minutes before the action started. I wanted a short exposition with A Faithful Man where the action starts quickly, especially since it’s a love story and it was expected that Abel was going to speak a lot about love. I wanted to put the action right at the beginning. I wanted to keep the attention of the audience and never let them go. So making a movie is exactly like telling a story to somebody. For example, when something funny happens on the street, you want to tell that funny story to your friend. You want to recreate the atmosphere so you have to make it quick, and sometimes you fail, because you’re taking too long in the beginning. It’s like your friend will say: “Can you tell me this story another day?” You have to learn to be quick.

Right—it gets less funnier to you as well as time goes on that you’re not relaying it.

Exactly. For me, with that movie, I wanted to be exact and precise to get your attention all the time.

When you have an idea for a movie, are you in a mad hurry to get it out right away?

It depends. It’s connected also to the desire of making a film with a certain actor or an actress. I try to organize a story that I want to make with this actor or this actress. I wanted to work with Laetitia for sure. I met her on the set of Les rêveurs. Then I started to connect Laetitia with Lily-Rose and then with Joseph, the kid, you know? I didn’t have to do casting with Joseph because I already knew him. I write for people.

We’re at that same stage again, like after Two Friends. Do you have a third feature?

Yeah, yeah. I wrote a script. It’s a story about a man who’s going to be involved in illegal things, but without the desire of being involved. I’m trying to write a story about that.

You have Greta Gerwig’s Little Women coming up.

We’re shooting that right now.

Did you like Lady Bird?

I liked that movie. I like Saoirse Ronan a lot.

You’re our culture marker right now. You have a Roman Polanski movie, which is obviously controversial. Are there always different factors that attract you to projects?

In general, it’s evolving. When I started, I was very close to Honoré, for example, because I like to work with ensembles. I think it depends completely. It’s a different story for every movie. When I did Saint Laurent with [Bertrand] Bonello, I didn’t know how to play Yves, and then it’s like, “I want to play Jacques de Bascher!” So it’s different all the time.

You’re just going from project to project.

Of course. It’s the relationship with the director, also.

Are you more interested in one over the other in terms of acting and directing?

I’m still interested about both things.

About a Boy: James Norton

About a Boy: James Norton Clarion Call: Garrett Hedlund

Clarion Call: Garrett Hedlund

No Comments