Whatever you think about the film—even if you believe you despised it—you’re going to walk away with the residue of it.

“Later on, when you’re looking back at this occasion, I think that right there’s going to be the moment you wish you’d done something,” says Daniel Gillies’ unflappable sociopath in James Ashcroft’s confident debut feature Coming Home in the Dark. Chillingly delivered with all the offhandedness of a remark about the weather, it signals the beginning of a waking nightmare for a family on what should’ve been an idyllic day out in the scenic wilds of New Zealand’s coastline.

Middle-aged schoolteachers, “Hoagie” (Erik Thomson) and his wife Jill (Miriama McDowell), have whisked their two teenage sons away for a family getaway. But no sooner have the clan sprawled out for a lakeside picnic when two strangers emerge into the clearing: Mandrake (Gillies) and Tubs (Matthias Luafutu). Unappeased after the family hands over their possessions, the men turn irredeemably violent. They clearly have a protracted ordeal in mind when the family’s SUV is repurposed for a night of torture and interrogations—the excavations of a shared, past trauma.

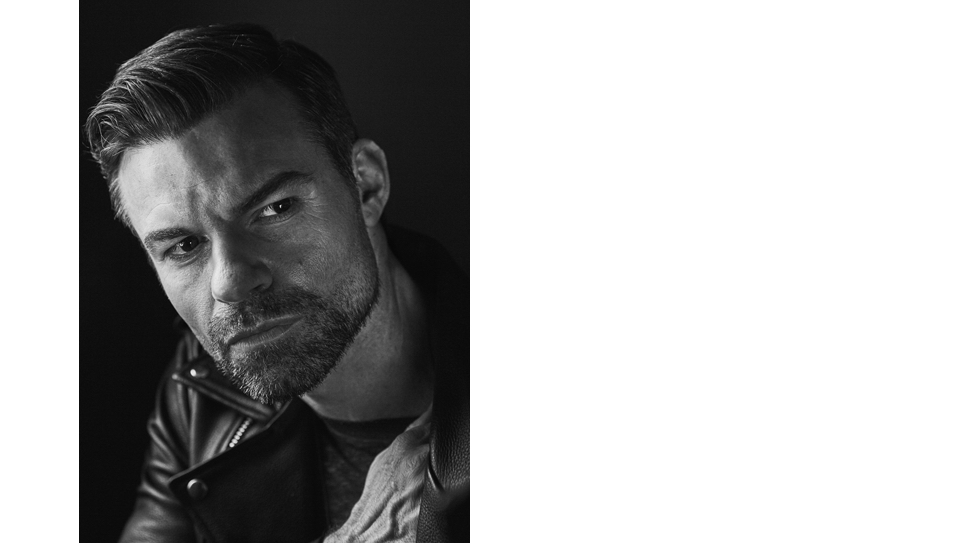

Coming Home in the Dark was adapted from leading Kiwi author Owen Marshall’s 1995 short story of the same name, which Ashcroft and co-screenwriter Eli Kent have fortified with real-life scandal. It’s best experienced as a blind-watch. As far as performances go, Gillies—by turns sardonic, terrifying, and alluring—is a complete knockout. The actor brings a wiliness and charm to the role, luring viewers into a false sense of security. This is one of the year’s best performances.

Coming Home in the Dark hits select theaters and VOD on October 1.

So, you’re spectacular in this. I can’t say enough good things about this performance.

Thank you, man. That means a lot to me. Now you’ve put the pressure on.

I understand you had quite the visceral reaction to reading this screenplay.

Yeah, and I almost regret ever bringing that up because everybody brings it up now. [laughs] But I did. I was quite vocal, I will say. Because the movie sets itself up as one thing, leading you down a path. Then it takes a hard left, you know? It’s what anyone would do when they read something: In your mind, you’re guessing where the narrative is going to travel. I’d made this story in my head that it’s about the boys and perhaps the one with more mischief was going to invariably save the day. So I thought it was going to be a story about these boys. I wondered where my role was, actually. Then 15 minutes in, something descends on the film, and it’s me and my cohort.

You must’ve read tons of material in your time. That kind of reaction is rare, is it not?

Yeah. Most material looks like everything else, and this just didn’t. That’s the reason to do it.

On my end of things, even as I’m consuming movies constantly—I saw this at a genre film festival in South Korea and I was doing four, five movies a day—it’s uncommon that I single out a performance to this degree. You were perfectly cast and I’m certainly not alone in thinking that. Variety called it “a career-changer.” First of all, is there a career to change?

Yeah, definitely. Look—no matter what you do, if you become known for doing something, people believe you’re that one thing, especially if you received a certain amount of exposure for that thing. So people definitely thought I was that, you know? They forget that there’s such a thing as versatility. And that’s totally understandable. I totally get that. In terms of “career-changer,” I’ve always remained a little skeptical of comments like that because, while it’s a beautiful and a very charitable thing for them to say, I’m also cognizant of the fact that there is a deluge of entertainment and films out there right now. Knowing that, even good films, great films, can get lost. Actually, I have a question for you: What was the response like with the Korean audience?

I actually find that really difficult. Because I think it’s uniquely Korean that it’s hard to get a reading on audiences when you go to the movies over there. They’re just so quiet.

They’re great filmmakers. South Korea makes some of the best films in the world, and have for years. My girlfriend is addicted to the K-dramas. I actually sat down to watch some of it with her the other day. I was kind of stunned at the production quality, stunned by the performances. Even what you would consider “pedestrian” dramas are just so beautifully executed. I was blown away.

A lot has been written up about just how dark this movie skews—this unrelenting sense of brutality. What surprised me is how much I sympathized with your character, in spite of his violence. It made the film resonant and multi-dimensional. Did you like him right off the bat?

When I’m first reading something, I’m reading it to see if the story makes sense and if this is a narrative that I think is really interesting, or the world needs. I also just want to see something original and raw. To me, it was reminiscent of Michael Haneke’s Funny Games, you know? It also had a South Korean and Swedish texture to it. You can see James’ [Ashcroft] influences in the film. In that sense, I think it will have a kind of global appeal. I wasn’t really concerned whether he was likable or not when I first read it. I never worry about whether I like a character—that never enters my consciousness. The task when you get into a character like that is to find where to love them. That took some time. In fact, I started to panic about it. I had about two and a half months before we started shooting. I did a lot of research and a lot of work. I started to panic a little as we were approaching the shooting days ‘cause I hadn’t quite found where my love for him was.

You hung out with ex-convicts in your preparation, didn’t you? And you did that in secret?

Yeah, this was when I was panicking a little bit. I told no one, including James, because I might have been dissuaded or recommended heavily against taking those actions. But that informed me more about who he was than any of the research I might have done, whether it was in books or from reading up on criminality from Mount Eden, which is a large prison in New Zealand.

Mandrake is mysterious throughout, by design. What felt essential that you had to know?

The most important thing is: Who does he surround himself with? And I did that last. It was the most helpful thing, I think. And yeah, you have to create a backstory. No matter what role you play, even if they are characters that vomit their exposition, you still need to do that creation before you get to the set no matter what. It’s kind of the most laborious stuff, but it’s also the most fun. You let all that stuff go when you go to set anyway. You just see what sticks.

Does the short story provide a more fleshed-out portrait of who this man is?

Well, the book is a very different animal. I mean, animal is a pretty decent word or an adjective for him, you know? He’s this sort of creature of violence. The short story is making a very different statement than the film is. And it’s quite brief, I think. It’s 14 or 15 pages long. It’s sort of one act. I think Owen Marshall was really talking about how insidious darkness can lurk even in a place as idyllic and ostensibly utopian as New Zealand. I think James maintains that in the movie, but once night falls, you’re buckled in. He and Eli Kent, the co-writer, made this whole other universe.

When I first watched the film, I had guessed it was based on a true story. It’s not, although it does explore a very real, dark corner of New Zealand’s history. Are Kiwis at large privy to it?

A lot of people are.

It’s a very confronting subject.

Yeah, and James’ brother was subjected to that kind of institutionalization. We all had friends and acquaintances and family members that we knew had been through those systems, which were kind of covertly tyrannical during the 1970s and 1980s. And that’s not unique to New Zealand.

Every country has a sordid history it seems.

It’s true. Growing up in New Zealand during the 80s and 90s, we’re also very aware that people would go into the wilderness and vanish without a trace. Some cases are unsolved to this day.

Let me throw your question back at you from earlier: What has the response been like with New Zealand audiences? I would think it’s divisive, especially if it’s hitting so close to home.

That’s the perfect word for it. Immediately upon reading the script, I knew, “If this is done well, it’s going to be polarizing. And everyone will be affected by it.” That’s the most important thing, really. Whatever you think about the film—even if you believe you despised it—you’re going to walk away with the residue of it. You won’t be able to shake it for weeks, months. There was a guy who finally reviewed the film a couple of weeks ago for The New Zealand Herald and he said that he’d seen it in January. He said, “I still think about the film several times a week.” So the response has been pretty strong. New Zealanders actually have a funny quirk/idiosyncrasy in that—I’m generalizing here—they feel like every film that comes to New Zealand needs to represent the place with some degree of accuracy. But I don’t think that’s what this film is about. It’s not a historical document necessarily. James and Eli pose a philosophical conundrum, you know? They’re asking you questions, leaving that vacuum kind of open for you to discuss with each other and yourself: What do you think you might do in these situations? That’s why it’s so defiant. The film defies categorization in a lot of ways. I was just talking about this with someone yesterday: What is the film? I think it’s sort of a psychological horror. It’s not typical horror. It’s a thriller, but it’s not an amusement park ride. It’s philosophical. I don’t want to ruin anything, but when you get into the meat of what Hoagie’s history is, you start to realize what is really happening in the film.

I’ve come to learn that you were born in Canada, but grew up in New Zealand. This marks your first New Zealand movie. That must carry with it some significance for you.

It has a huge significance. I mean, I’ve turned down a few things back home just because they didn’t quite seem like the right fit. And not that I’ve had an avalanche of offers. I was very, very fortunate to have this come my way. And I very nearly couldn’t do it because we got delayed for one reason or another. But I always sort of knew that this was quite an opportunity and a shot. I could feel it, discussing with James and having seen his previous short films. He made nine of them or something before this. He’s a very worldly guy. He’s had a lot of experience both in theatre and film. I just knew that this person was going to do something special. I’m very, very grateful.

When a performance is this well-received, I can only guess that you’ll be fielding more and more offers—perhaps for similar roles. Are you particularly interested in playing villains?

Well, I never really regarded Mandrake as a villain. I still just see him as a person. But looking at it with a bird’s eye view—from the audience’s perspective where he could be this villain—I’ve been playing these guys for years. And they’re just more interesting to me. I did receive an offer recently and this happened to be from someone who’d seen the film. Normally with the kind of offers that come in, I’m described as “clean-cut, dapper, elegant, a man of a certain level of education” or whatnot. Now it has become “mountain man, monosyllabic, looks like a reprobate.” [laughs] That’s one of the first offers that has come in after someone’s seen the film. I was like, “This has taken a U-turn.” It sort of speaks to what we were talking about at the beginning of the conversation: People’s imaginations are, unfortunately, constrained by what you’ve done already.

It’s scary to cast actors without first having seen them excel in a similar role?

I think that’s where it becomes a little unjust. That’s where things become imbalanced, I think. Because what happens is, oftentimes people will see a taping that you’ve done for them of a character and it doesn’t really matter how good it is. They’d rather make offers to established stars who’ve done that role in the public eye. There were several times in the last year where I’ve come incredibly close to getting things because my tapes were so liked. But simply because I haven’t done a role like that quite publicly, they’d rather think of you as your last big thing or your last big performance, or what you’re most known for. That, for me, I guess for good or for worse, and rather iconically, is Elijah Mikaelson [from The Vampire Diaries and The Originals.]

That’s a huge gift, too. I’m sure most actors would kill to have what you have. Do you also have plans to write and direct and star in something of your own creation again? I understand you had quite the journey with your directorial debut on Broken Kingdom.

Yeah, I did. [laughs] I’m writing something now. I don’t know who’d make it because it’s pretty challenging material, which is obviously the stuff I’m most interested in. It’s kind of graphic. It’s very sexual and very violent. I just wanted to make something that I hadn’t seen before. I have every intention to make it and I think 2022 is the year that I either get it well underway or begin.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments