I’m having a really good time acting. I’m enjoying work now more than I’ve ever enjoyed it.

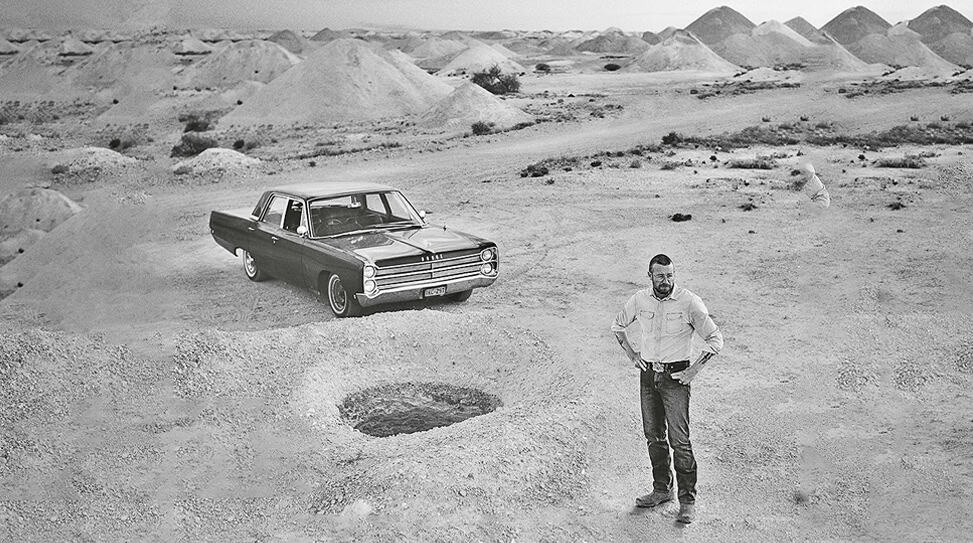

In biblical terms, Limbo is the border place between heaven and hell where unbaptized souls go to get sorted. In common parlance, limbo is, of course, a state of indecision—forced inaction. For filmmaker Ivan Sen, such a place is Umoona, the Indigenous name for Coober Pedy in regional South Australia, which he repurposes as a town called Limbo, from which his film also takes its title. Captured in spartan-looking monochrome, it resembles some distant planet drifting in time and space, and haunted by the past and not expecting much from the future. This is no coincidence as limbo also describes the position of its citizens: Indigenous people pushed to the fringes, and whose lives have been upended by generations of racial inequity and distrust that fuel roiling undercurrents of tension. Limbo joins a long line of Australian films that have taken to the desert to disinter racial trauma—to rebury the bones with more care and awareness, but also enduring fury.

Simon Baker is Travis Hurley, a detective with a downbeat, Walter White-like demeanor who has blown in from far away to review a cold case in which a young Indigenous woman vanished twenty years prior. At the time, the police bungled the investigation, beating a confession out of basically any Indigenous person. Small wonder that Limbo’s inhabitants are loath to talk when another pale out-of-towner comes sniffing around. Meanwhile, Travis is in a period of his own perpetual limbo-ness. A broken man with a full set of skeletons in the closet, his family life has disintegrated and he’s in the throes of a heroin addiction. Travis’ superior has clearly given him this dead-end assignment as a means of getting him out of the way. But there’s something about this stoic, unsmiling man that wins the confidence of those he encounters. Perhaps it is the fact that he’s every bit as damaged as the drifters and outlaws who have ended up living in this blighted place.

This is a role that virtually redefines Baker’s career as an actor in a time of his creative renaissance.

Limbo opens in LA and NYC on March 22, with a wider national expansion to follow.

[Editor’s Note: This conversation has been condensed and lightly edited for length and clarity.]

This just might be my favorite performance from you, Simon. You’re only getting better.

Aw, thanks, Kee. That’s very flattering.

Limbo is also my official entry into Ivan’s [Sen] work. You’ve rightfully called him an auteur. He’s a one-man band with the writing, the directing, the shooting, and the music. And by his own admission, he’s a fan of cinema, but hasn’t seen much. He’s “uncorrupted” in that way.

Yeah, definitely. Here’s the thing about Ivan: Whether you like all of his films or not, he has a very clear point of view. Like you said, he isn’t necessarily influenced by other people or other films. He pretty much sets out and does what he wants to do. He’s a purist. He’s like a painter: He commands every brushstroke from beginning to end. I’ve made a feature film myself [Breath] so I appreciate that kind of craftsmanship and artistry enormously. I was able to collaborate quite closely with him ‘cause it was a very intimate setting as you can imagine. The maximum number of people we ever had on set was fifteen, so there was a real connection between the writer-director and the actors.

I understand that you first met Ivan many years ago when he was just out of film school. It was on a project that never came into fruition. What were you guys collaborating on?

I can’t remember exactly. [laughs] It was twenty-something years ago. But it was a futuristic piece. It was a detective story—a Philip Marlowe type of thing. Ivan likes to play in that world of broken characters where people are flawed, but not necessarily all bad. He likes to live in that world. Ivan’s a curious dude. He marches to the beat of his own drum. I love working with different types of filmmakers and studying their approach. The longer I’m in this business, the more I start to understand that there’s so many different ways to approach any kind of story. I love getting to make films. That’s not to say I loved every film I’ve ever worked on, but I love making something. I’m in the middle of shooting with Taika [Waititi on Klara and the Sun], and he’s so different. Every job is a vastly different experience. Late last year, I worked with Justin Kurzel on a limited series [The Narrow Road to the Deep North]. Again, Justin is completely different. For me, it’s exciting to arrive on a new set, get to know how directors work, and figure out how I can serve the story they want to tell. That’s something I find really thrilling as I’ve gotten older. The anxieties of having to perform have subsided and there’s more of an excitement to go to work.

How great is it that the universe brought you back together? Perhaps at a better time because you and Ivan surely come with more knowledge, skill, and life experience under your belts.

I totally agree. We’re both probably a lot more comfortable in removing the doubts and fears from the process and just throwing ourselves into it. I certainly feel more like that at this stage in my life.

And this wasn’t your first time filming in Coober Pedy. You shot Red Planet there, right?

Yeah, yeah. That was another wacky experience. [laughs] I had stayed in the same hotel. There’s been a fair few films shot in Coober Pedy. I think Ivan’s choice to shoot it in a monochromatic palette was great. It made the place feel otherworldly. It’s strikingly beautiful as is, but when you’re out there, the colors are so rich and interesting that it would’ve detracted from the subtlety. When you’re dealing with that gray scale, you can be more subtle as a performer and in the nature of the storytelling because the drama tends to lift a bit more off the screen. We’d probably be more distracted by processing the beauty of everything had it been in color.

Location is obviously crucial, and not just to serve as a backdrop in which to tell this story. I learned that Ivan scouts the locations himself and it’s the preliminary step in his filmmaking. There’s good reason for that: The land is everything to Indigenous people. I suspect you can relate as a proud Australian. After establishing a career in Hollywood, you returned to Australia and continue to live there. You’ve been very supportive of the local film industry and homegrown storytelling. As far as I can tell, you’re deeply tethered to your roots.

I really am. But I don’t feel burdened with a sense of responsibility to the place so much as I feel it’s a honor to be able to come back here and tell these stories. Australian cinema has a reputation for being a lot about the environment. Indigenous Australian culture is a storytelling culture, and the first Australian stories were told through paintings and song and yarns. It’s not a written history—storytelling is in the fabric of its land. And we do struggle with our past. The colonized history of this country is difficult for a lot of people to reckon with. In a lot of cases, we don’t necessarily reckon with it. But there’s a really powerful way to reckon with it through stories in filmmaking.

So you believe in cinema’s healing properties.

I believe it has an unmatched ability to connect people and healing comes through connection. I think film is the most empathetic form that exists. Connection is where people do heal.

And not only to what’s happening on the screen—it’s the communal theatrical experience.

Exactly. It’s unmatched.

This is a wonderful character study as well. Travis is broken. Among other things, the image of a father who’s no longer with a child is striking. You’re a father, Simon. Although your character’s circumstances are specific and quite bleak, I’m sure you can still relate to the guy.

Oh yeah, absolutely. There’s that dinner scene where he’s talking to Natasha’s [Wanganeen] character. She asks, “What happened?” and he says, “I was married once. She left. She found someone better. I don’t even really talk to my son anymore.” So he disappeared from the realm of being a husband and a father. He’s sort of lost. I think this happens to a lot of men. You find yourself focused on building a family and providing for the family and doing all of those sorts of things and then, for one reason or another, relationships break down and what you once felt was your role in the world is challenged. You’re trying to find who you are now and where you fit in the world, whereas before, you had a more clearly defined purpose, as structured as it is. I think that’s what happened with Travis. If you are destabilized and untethered, things are on the decline and you’re in a negative cycle. In the last few years, I went through a marriage breakdown of my own so I could completely relate to the idea that you can feel sort of worthless. I mean, I think I’m probably a little more aware than Travis, I hope, but I could certainly relate to the idea of spiraling.

There’s one character detail you engineered, perhaps accidentally. The way Ivan tells it, when you read the script, you thought Travis was shooting up heroin, when in fact he was diabetic. His drug abuse adds another layer of vulnerability. And he has to be that vulnerable, right? He’s no longer a threat to the marginalized people he’s tasked with interrogating.

Yeah, they breakthrough to him. That’s the thing. They crack him open. Their kindness, generosity, pain, and struggle open him up in a way that I feel brings him closer to redeeming himself.

And salvation? The film is littered with religious undertones, like the sermons that are on a loop in his car. I mean, it is called Limbo. Travis has angel wings tattooed across his back.

All I know is that, if he’s to be saved, he’s gonna have to save himself. I think he has a newfound awareness of that. It ain’t gonna be evangelical CDs or religion or anybody else. It’s gonna be him.

As for your next directorial feature, Collider coaxed a title out of you: The Shepard’s Hut.

I’m not doing that anymore. [laughs]

Well, that was quick!

To be completely honest with you, Kee, at the moment, from Limbo to Boy Swallows Universe and The Narrow Road to the Deep North to Klara and the Sun, I’m having a really good time acting.

That’s such a gift. I’m happy for you, Simon.

Yeah, it’s maybe the best time I’ve ever had. I’m enjoying work now more than I’ve ever enjoyed it. I’m really relishing the opportunities. It’s filling me up. Looking back on the seven years I did that network TV show in America [The Mentalist], for all its success and the opportunities it afforded me, I felt creatively in a rut because of the nature of the workload on that particular job. So it’s really nice now to be able to jump into different boats with people and engage with the different ways of making films. I’m also at the age where I can play these kinds of characters, as opposed to being physically typecast as I probably was when I was younger, which is inevitable. If there’s anywhere in the world that does that most, it’s America. They love to be like, “This is how we see you,” and if they don’t know how to put you into that box, they stand around confused. I feel like I’m outside of that now. I can play more. And that’s been really, really enjoyable.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments

Comments are closed.