I suddenly realized the oxymoronic nature of who and what Joel and Ethan are as directors and filmmakers.

In a career spanning over three decades, Joel and Ethan Coen have been there, done that—and more often than not, successfully. The critical darlings have a massive cult following and remain exceptionally clever artisans whose manipulation of the audience is an art onto itself. Their latest, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, is a six-part Western anthology that sharply moves from picturesque sentimentality to grisly violence. There’s barely a forehead that doesn’t find a bullet in it, in time.

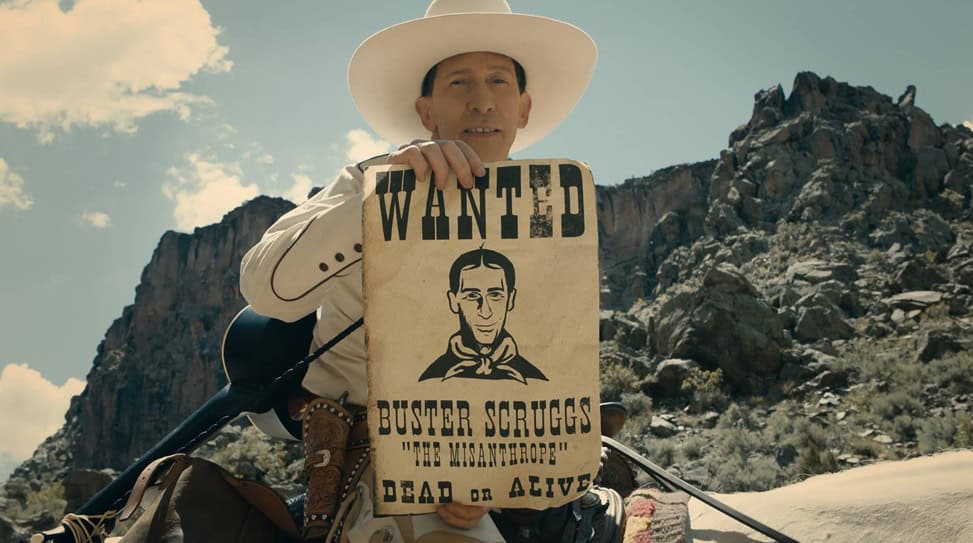

A book called The Ballad of Buster Scruggs and Other Tales of the American Frontier serves as the film’s framing device. In the opening vignette, Tim Blake Nelson is our titular hero, a warbling balladeer in a pristine-white 10 gallon hat, who strolls through a dusty town sizing up locals against his moral code—always scrupulously polite, even when he’s on a murderous rampage with his over-the-top gunslinging. He’s just one of many Western archetypes that are given the Coens treatment: a bearded prospector (Tom Waits) scours an untouched American Eden for a pocket of gold, a would-be bank robber’s (James Franco) devious plans are upended by an unlikely adversary (Jim Broadbent), a young woman (Zoe Kazan) with an uncertain future ahead of her falls in love with a fellow traveler (Bill Heck) on the Oregon Trail, a mountebank (Liam Neeson) wanders from town to town with his limbless sidekick (Henry Melling), and a bounty hunter (Brendan Gleeson) shepherds a motley crew through the void of nothingness in a stagecoach. This is cockeyed storytelling that so often merges comedy with despair. In other words, it’s a Coen brothers movie.

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is now in select theaters, before hitting Netflix on November 16th.

Can you trace this back to the very beginning? Which story came first in the anthology?

Joel Coen: I think the first story was the first segment in the movie, wasn’t it?

Ethan Coen: Yeah.

Joel: These were written over the past 25 years so the first one goes way back. They follow a fairly chronological order in terms of what came first. They got put in a drawer because they were short and we didn’t know what to do with them. We probably weren’t expecting to make them until maybe 8 or 10 years ago when we started to think, “Maybe we can do them together.”

How did you order them? They follow a certain rhythm, but they’re also very different.

Joel: When we’d written five out of the six, right?

Ethan: Yes. We didn’t really think of the order in terms of how to order them. They kind of fell into an order by the virtue of the way in which they were written. I’m really good with words… [Laughs] We looked at it and thought, “Oh yeah—that’s a good order.”

Joel: They could sort of be seen as a sequenced series of stories or a transcendental record or something like that. It was a weird animal.

It was nice how you started with the Sons of the Pioneers music, beautifully rendered by Tim.

Tim Blake Nelson: Now we can say we did that. [Laughs]

Your word play is always second to none. Do sayings like “pecking Pythagoras” and “jibberings of nations” come up in the first draft or do they come in stages?

Ethan: It’s funny to think of a pass where we put in funny words. [Laughs] That does not happen.

Did you at any point have the impulse to merge the stories together in a more cohesive way?

Joel: Into one, grand Balzacian thing? No, because they were all Westerns and they all seemed to relate to each other that way. But they did all relate to each other kind of retrospectively, rather than consciously as we were starting to do them, obviously. So no, there was never an impulse to merge them in the way you’re talking about. As I said, it’s a strange form, but it grew out of just the odd nature of how they came into existence in the first place.

I know each chapter was shot separately like its own movie. Tim—how did it feel to see yours within the whole of the anthology?

Tim: Well, we all got to read the stories. We all got to read the entire script before we shot our individual constituent parts that are unrelated to the others. I think as actors we all felt a responsibility towards the genre of each film in which we appear. What I think is astonishing about this is that it’s six different movies within the Western genre, but each one is in the vernacular of a sub-genre in and of itself. At least with me, and I’m pretty sure with the other actors as well, it just underscored one’s responsibility to appear indelibly within the genre in which you appear. To understand that and to see the successes of others—like Bill Heck and Zoe Kazan in the covered wagon segment—was just really rewarding. I think Bill and Zoe are so perfect in that and it fits so well in that genre in terms of their acting styles. It was great to encounter that in all the stories. That’s what was the most gratifying about seeing the whole: experiencing the successes of others.

At one point, this was rumored to be a series for Netflix.

Joel: I think that’s an artifact of what a strange animal this is. None of us really knew what to call it or how to classify it. But aside from the issue of confusion about its classification, the actuality of what we were going to shoot, and the length of the stories that all vary, there was never something that we were considering doing any differently. There were never more stories and they were always intended to be seen together as a group.

This is a huge ensemble, not to mention all the other living creatures you added to the mix.

Joel: Flies are very hard to work with. [Laughs] Yeah, you’re right. There are a lot of animals. Maybe that’s just reality of the Western. We do tend to sort of load the movies up with domestic animals, don’t we? Anyhow, it’s a Western with horses. It’s true that if you do a Western, you spend 90% of your time dealing with and thinking about the horses—

Ethan: And the oxen. The oxen were new to us. We had an oxen wrangler because we wanted the oxen to do something specific in a take. I asked him if we could do that and he just sighed. He looked at me like I was an idiot and said, “To drive an oxen is not self-evident.”

There’s one very memorable scene where Jim Broadbent is charging at James Franco, taking all the bullets in his makeshift armor made of pots and pans. Has that ever existed on film?

Ethan: I think we came up with it! It’s pretty specific to its context. [Laughs]

Carter Burrell’s partnership with you on the score is in fine form. What did you guys discuss in regards to finding unity in the stories that are actually quite different from one another?

Ethan: Yeah, that was interesting and it’s something that we talked about a lot. In terms of genre, they’re all Westerns, but they’re all such different kinds of stories. We talked about to what extent the music should play off those different things and to what extent the music should tie them all together. We pretty much ended on—I guess you would have to—the music playing what the thing is. It doesn’t play the unifying thing, except the obvious and literal way the overture is in the title, which you see again in the end credits—that unified things musically. It’s an interesting question that we confronted. With all of them, they’re so different, so how much are you planning on accentuating the differences and how much are you going to say that it’s all the same movie? There isn’t a uniform answer. It’s just something that we always confronted.

Joel: The lucky thing was that, with “The Streets of Laredo,” which is such a familiar tune, we knew from the beginning that we wanted to have Brendan [Gleeson] sing what is essentially an early version—the Irish-Scottish version where it comes from. Using that at the beginning would help link things up. The question you’re asking is actually something that we talked about a lot and it wasn’t just related to the music. It’s also an issue that came up with the shooting styles and the kind of color-timing look of the movie. How much do we differentiate between the different stories and how much do we not do that? How much do we push that and how much do we pull back a bit in terms of our original instincts about it? That went through a lot of iterations. It’s the kind of thing that’s very easy to iterate and reiterate now that color timing is done on the computer as opposed to photochemically. That went back and forth a little bit and sort of found its place in the end. So as Ethan was saying, you put a finger on something that was very much discussed.

Tim—a few years back, the Film Society Lincoln Center put on an anniversary screening of O Brother, Where Art Thou? and you went into great detail about your experience working with Joel and Ethan. How do you think your work has evolved with them?

Tim: Well, they finally know what they’re doing. [Laughs] They figured it out on this movie. Referring to a press conference we had earlier, I suddenly realized the oxymoronic nature of who and what Joel and Ethan are as directors and filmmakers. They’re incredibly, unbelievably, and in an unparalleled way meticulous and prepared as filmmakers. When you get to set, there really are no decisions being made during the shooting time that could’ve been made earlier. That rigor pays off in an interesting way because it allows for the actors inside of that meticulous preparation to be utterly free, to have all the time an actor could possibly want to have with this very careful writing, and shoot in a very careful and specific way. So I think it’s the amount of preparation that I’m familiar with from O Brother, Where Art Thou? that I never encountered before on any movie I’d done with any director or directors. It’s repeated once more here with The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. This is with the added challenge that Joel and Ethan had in making, effectively, six films with six different linguistic principles inside the language of a Western. I found the specificity with which they were working on the segment I’m in—a sort of Gene Autry singing cowboy aesthetic—unbelievable in terms of its extremes and its fearlessness, and the way that they were pushing me and in some cases allowing me to do certain stuff. Then seeing the whole movie with five other versions of that was truly astonishing. I guess what I really mean to say is that the opposite of my joke is true: they continue to be unparalleled in terms of the work they put in, the preparation they do, and the specificity that’s born out of the shooting and also in the result.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments