As you say, there’s something in his eyes that is lost. I think he has the look of a person who’s never at home. He’s eternally homeless.

Broadly autobiographical, Nadav Lapid’s Synonyms continues the filmmaker’s forensic, career-long fascination with the impossible knot that ties a person to their country. He had once struggled to shed his Israeli skin, trying with all his might to adopt a new, French persona.

When we meet Yoav (newcomer Tom Mercier), the former IDF soldier has fled Israel not long after his mandated stint in the national army. He’s pacing his way through Paris’ Left Bank like he’s on a drill, towards a cavernous, unfurnished apartment. He drops his meager belongings. He takes a shower. He’s robbed of what little he has. He runs naked into the stairwell, frantically knocking on doors. A neighboring couple, Caroline and Émile (Louise Chevillotte and Quentin Dolmaire), finds him unconscious in the bathtub. They revive him, in a manner of speaking.

With only a lip ring to his name, Yoav gifts it to the couple for their kindness. They feed him, dress him—Émile’s fashionable mustard coat will become his uniform—lust over him, and take apart his past for their creative inspirations as artist and author. Then they send Yoav off, this time to a squalid, almost certainly illegal, bedsit on the other side of the Seine. Strapped for cash, he eats the bare minimum to survive and crashes parties for the food. Simultaneously, he repudiates the Hebrew language, insisting on communicating only in French even at the Israeli Embassy where he’s briefly employed. This stubbornness is at times met by impossible situations that absolutely demand he speaks Hebrew. In one jolting scene, he poses naked and touches himself for money, shouting in his mother tongue at the insistence of a pushy pornographer. In a kind of pidgin French he’s cobbled together with the help of little more than a pocket dictionary, Yoav tells Émile that Israel is “nasty, obscene, ignorant, idiotic, sordid, fetid, crude, abominable, odious, lamentable, repugnant, detestable, mean-hearted”—words that help give the film its title—to which his friend replies, “No country is all of that at once. Choose.” Yoav simply can’t. He bounces around socially and politically loaded situations in this way, like a ball attached to a paddle board.

Synonyms received the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival this year, making the 44-year-old filmmaker the first Israeli to take the top honor in the festival’s nearly 70-year history. Knowing that the film might prove controversial in Israel and France, Lapid made a plea to audiences: “I hope that people will not look at this film as a kind of harsh or radical political statement because it’s not.” He was most certainly bound to face accusations of having made an anti-Israeli film. Meanwhile, home to Europe’s largest Jewish community, France has seen militant attacks on Jews and Jewish institutions in recent years, sparking concerns about resurgent anti-Semitism in the country. Beyond these blowbacks—and more than anything—Synonyms is a meditation on the hopes and perils of fractured identity, assimilation, and willful self-reinvention.

Surprisingly, Lapid has only made three films across his 16-year career. Synonyms comes after The Kindergarten Teacher—remade in the U.S. starring Maggie Gyllenhaal—and his debut, Policeman.

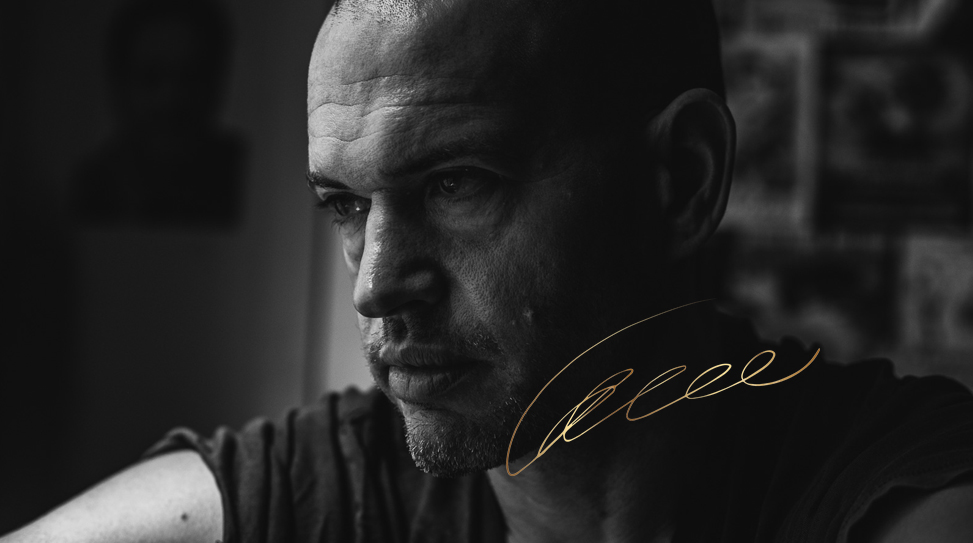

Anthem met up with the auteur during the New York Film Festival for a conversation and portraits.

Synonyms opens in select theaters on October 25.

You must get asked this in virtually every interview: just how autobiographical is Synonyms? Let’s get a little more specific. You’ve said before that “French became a pathway for redemption. Every word I studied was a triumph over the past.” What were you running away from exactly? It’s rather ambiguous in the film. Having read up on your history, it appears that after your military service you went back to your life as normal and everything was fine. Something must’ve clicked inside of you that prompted this sudden move to Paris—almost like a divine thought.

This is a very good question. Maybe one of the strongest, most distinctive things in the movie is the fact that you can curse Israel with all the negative adjectives you can find in a French dictionary—and you can feel Yoav’s rage—but if you were to ask him, “Tell me in one sentence, what’s the problem?” he wouldn’t be able to. He of course has a past in the military service, but if you try to understand the moment that made him turn his back on Israel, you wouldn’t find one event and he wouldn’t be able to define it concisely. In a way, I think it’s based on a certain compulsion, a certain vibration, and a certain movement. It’s not based on a specific argument, which turns this into something much more radical and extreme. When it’s an argument, one can say A or B. But if you feel that a demon is inside of you and you run from left to right and from right to left, it’s of course much more powerful, much more desperate, much more hopeless, and I think in a way closer to the truth. Yoav tries to sum up things in existence into one sentence, but I feel that in the end they’re movements and forces.

Sometimes people ask me if Yoav has post-traumatic stress disorder. I don’t know if he does, but if so, his trauma is life—life in Israel. It’s not one event. That’s why I think in the end he’s running away from a certain collective Israeli soul, which is also his own soul. This is not a right-wing movie, but it’s also not a left-wing movie in a way. It’s hard for me to talk about this as a political movie. Maybe it’s a political movie, but in a broad sense. It’s not on a narrow level like, this and this and this is not okay. Also, if you try to characterize the Israelis that Yoav encounters in the movie, I would say that most of them are young, tense, masculine, unsmiling men who love their country in a kind of nationalistic way where they hate everything else. They prescribe to this dichotomy between us and the others. Yoav goes to the opposing side where us becomes the enemy and the others become us. But of course he shares with them a lot of commonalities in the end, and that’s why he turns out to have the same symptoms, from the same sickness.

Let’s talk about the body—our physical bodies. Yoav’s body is symbolic. It’s his inherent Israeli trait that he cannot willfully discard. I mean, Émile’s very first observation about Yoav is that he’s circumcised. Yoav can adopt a new language, but he cannot erase his physical self. And the body that Yoav is torturing—the body that he degrades in one instance in the worst possible way for a pornographer—is also what we consider an ideal male body. It’s a beautiful body, which seems to conflict with Yoav’s self-hatred in a way. This question is going to be, I’m sorry to say, not so elegant. I was surprised to learn that the first time you saw Tom [Mercier] nude was on the first day of filming. Did you not need to know what he looked like beforehand?

[laughs] You’re right, I didn’t see him naked. But I did see him in his underwear so I knew what he would look like. In the first scene of the movie when he’s running naked in this huge empty apartment, I knew that he’s gonna look like a kind of Roman statue or a Greek statue—an Israeli statue. I never saw him totally naked so I did have this tension regarding his genitals. I didn’t know what that looked like, and that was okay. But it’s exactly like you formulated it: the body is a curse, but what a beautiful curse.

In the same way that there’s this conflicting force in hating something that’s beautiful, Yoav is often childlike and projects a certain naïveté, while trapped in this masculine, adult body—a soldier’s body. That feels important because, even in his aggressive irrationality and almost militant outbursts, you sense that he means well. It’s sweet that Yoav would ask a stranger, another grown man, to tie his tie. He has that look of being perpetually lost, too—a look of searching. Was that something you looked for in Tom?

On the one hand, I would say that he’s the ultimate fighter in a way because he’s all the time fighting this actual moment. He’s constantly fighting with himself. He’s someone who only lives in the present, and his way of dealing with the present is to fight against it. When you want him to be outside, he’ll be inside. When you want him to stand, he’ll dance. When you want him to whisper, he’ll shout. On the other hand, as you say, there’s something in his eyes that is lost. I think he has the look of a person who’s never at home. There’s such tranquility that accompanies the feeling of being at home and, to me, he has the eyes of an existential homeless person. He’s eternally homeless. In a way, you tell yourself that he’s going from point A to point B, but actually, it’s not movement. It’s more like vibration.

Maybe some people will look at the Yoav-Émile-Caroline love triangle as “modern” or “French.” That ambiguity is very real to me personally. Yoav and Caroline’s relationship is explicitly sexual, whereas you sense the homoeroticism between Yoav and Émile at every turn. You’ve said this before: “In a way, it’s a world where only men exist. Women are like silhouettes.” The affections and emotions that exist in the movie are only between men.

Yes, women in the movie are concepts and men in the movie are real human beings. I don’t know why it came out this way, but I can tell you with this movie I tried to go back to a certain feeling that I had as a soldier when I was in the military service. On a small military base, there were only men. You’re surrounded for three and a half years by men. There was no explicit sex to my recollection, in my experience. There aren’t even direct, explicit demonstrations of affection. In a way, this project translates all the emotions you have in that situation—love, hate, affection, fascination, attraction, hostility, everything—that’s addressed only to men because we are the only ones that exist. Women become a kind of concept—illusory creatures. Riding on the bus that takes you to the frontier, you would see maybe three or four women. So this is something you feel in the movie. The only demonstrations of really deep affections were and are between men.

The idea of running away from one’s past and that of self-reinvention are universal so you could feasibly set this story anywhere in the world. But France is perhaps an ideal choice because, not only does it mirror your life, it’s also a place of fantasy that exists in our collective imagination. Paris is maybe the most heavily romanticized place in the world.

Everyone wants to be French in a certain way. [laughs] They’re a “better race” of human beings.

No, it’s true. At the same time, it’s then much easier to shatter that illusion, which is exactly what happens to Yoav. That fantasy is broken, for instance, when Yoav senses for the first time that Émile is fed up with him. It’s shattered indefinitely when Yoav enrolls in a French citizenship class and he’s forced to confront things he doesn’t want to hear.

When you’re a foreigner, everything is challenging, including yourself, because everything is new and you’re new to everyone. Everyone knows that you only exist through them so it’s like a fantasy. It’s like the love affair of an animal or for the weak. Everything is permitted because none of us will stay here tomorrow. But then also, your relationship to the culture as a foreigner is based on fascination and admiration. You’re only in the position of the admirer—perpetually fascinated and charmed. Then comes the moment where you not only want to be your true self but to create your own small monument, a small corner of Paris, that hasn’t been applauded countless times like the Notre-Dame, Arc de Triomphe and stuff like that.

That’s why Yoav refuses to look up at anything in Paris.

Yes. It’s also this sanctified thing—the sanctity of France. As time passes, it turns secular. That’s exactly the moment where the magic is gone. The readiness of another culture to accept you as you are is being examined. It’s the moment that Yoav stops being a distraction to them and they’re ready to accept him. This is the beginning of the end of course because it obliges Yoav to embrace all of the French ways and he doesn’t care to be totally equal in that way.

Yoav has a transformative moment in the film where he tells Émile, “I need my stories back. They’re not so special, but they’re mine.” These are stories from Yoav’s past, which he carelessly offered up to Émile previously, but they’re now important to him. Yoav really is you in that moment.

Totally. This is the moment where you can tell that Yoav discovers himself as an auteur or something like that. Maybe he’s not the best auteur, but he has something of himself. Without his stories, he’s empty—it’s a total void. The moment that you own your stories, all of this fantasy of dying in order to be reborn is totally ruined. The moment you have your stories, you’re no longer a baby. You cannot fake it like you were reborn five months ago because you have stories and, for the best or for the worst, you’ve rediscovered yourself and you cannot ignore who you truly are.

What’s your next chapter?

I’m actually going to start shooting a new movie in two months. In a few words, I’ll say that at the center of the story is a movie director who goes to the desert in Israel for the screening of one of his movies. They were talking about the movie in a French newspaper and the way they described it is maybe not a bad one: throughout one afternoon, he suddenly finds his movie stuck in hopeless battles—one against the death of artistic liberty in his country and the other one against the death of his mother. This is something that might give a hint as to what’s coming next.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments