A movie can only be as good as your age... A movie is your age.

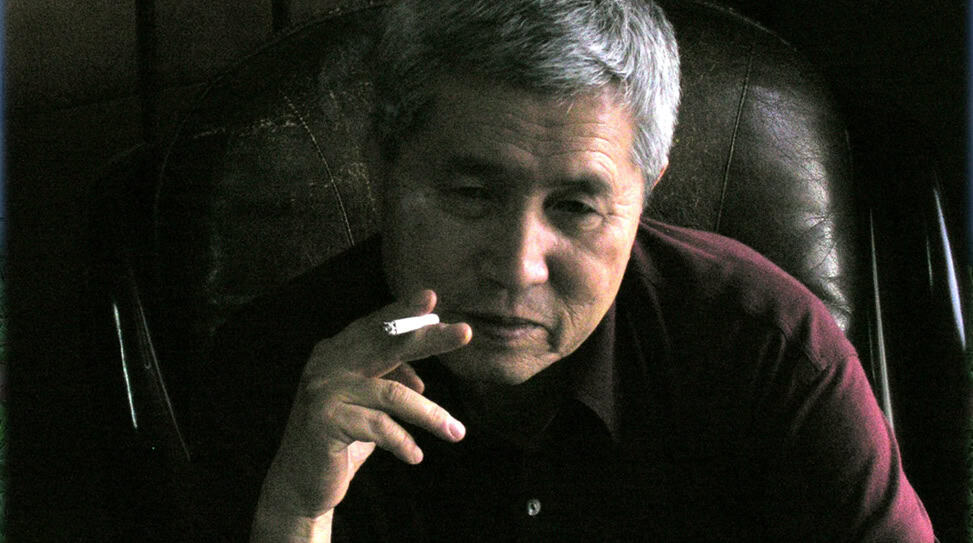

It’s doubtful there are many South Koreans alive who have never before heard of Im Kwon-taek. The legendary filmmaker has long been recognized as the most significant contributor to Korean cinema, having helmed 101 films to date in a still-ongoing career that began in 1962 with Farewell to the Duman River. Currently in production with his 102nd feature, Im has somehow managed to squeeze out several productions each year, working under military dictatorships and seeing Korea towards a democratic government. His films have garnered critical acclaim both at home and abroad—notably, Chunhyang became the first Korean film to enter Canne’s competition line-up in 2000 and 2002’s Chihwaseon earned Korea its first Best Director prize at the festival.

Before 1980, Im was known primarily as a commercial filmmaker who could efficiently direct as many as eight genre films a year, helping to fulfill the quota for domestic pictures set up by the government. His transition into arthouse cinema began to show itself with Jokbo in 1978, but 1981’s Mandala is considered by many critics to be the director’s breakthrough film as a true auteur. The lamentation of the vanishing Korean identity as the nation rushes to embrace a modern future is surely one of the themes continually projected in Im’s works since the late 1970s. Local but never provincial, proud yet never nationalistic, his films ask vital questions: What traditions should a culture preserve in the face of modernity? And how can it preserve them?

The 18th Busan International Film Festival hosted Fly High, Run Far: The Makings of Korean Master Im Kwon-taek, a retrospective featuring an unprecedented 71 of the director’s films.

A lot of piercing memories must come flooding back at the festival with this retrospective. How do you find yourself recalling the long, eventful trajectory of yours?

When I got my start as a filmmaker, I was making genre films. My aim was to try and copy what was coming out of Hollywood. In the first 10 years of my career, I made 50 of my 101 films. As a young man, these were “silly” movies made on very low budgets. Over time, it became an inarguable truth that trying to match the quality of American movies was not only a pipe dream, but ridiculous to think about. I would’ve been happy to even make 2nd or 3rd-rate movies that were on par with what was coming out of America, but I didn’t have the resources. I didn’t have the technical means to do that because Hollywood was so much at the forefront with the most-advanced technologies. This was a time of iconic filmmakers like Billy Wilder.

That’s when I realized I had to start telling stories that non-Koreans cannot tell. I started making movies about life and culture that’s unique to Korea. For instance, Pansori is a genre of traditional Korean music that captivated me and made into a film called Seopyeonje. I also wanted to make truthful movies without fabricating anything, so it was a complete 180. The first 50 films I made had nothing to do with the Korean people specifically. You’re maybe too young to have extensively learned about Korean history. Did you say you were 10 when you moved to America?

I was 8, but I’ve heard my share of stories from my grandmother.

I was in elementary school during World War II. Korea was in ruins with great poverty. There was a midnight curfew. These are the kinds of life conditions that I set out to capture in my movies. These are things that I personally lived through and felt confident portraying with a lot of realism.

Do you find sentimental value in those earlier films at all?

With this retrospective at the festival, I knew it would be embarrassing for me to show my earlier work to my fans. But I was sort of cornered and there was nothing I can do about that. I certainly don’t want to burn all of my earlier films, but I would like for some of them to go away. One journalist asked me if I would like the chance to remake those earlier films, but I have no desire to go back in time and fix anything. Although these were “silly” movies, I put my all into each and every film. So, while it’s embarrassing to revisit these films with my fans, I would probably make the exact same film if I were to go back in time. The experience of making those films made me who I am and taught me how to be a filmmaker, so I guess they have value in that way.

Your iconic status in cinema must afford you a lot of freedom. Do you perhaps also feel the need to meet unrealistic expectations or tell certain kinds of stories?

Of course, a director wants to make what they want. But your question makes it seem like I’m the kind of director who just gets to make whatever they want. [Laughs] While it’s true that I was able to make those 101 films based on my experience, each one of those films was such a struggle to make. Technology, techniques and certain skills can’t be used over and over again if your goal is to remain fresh. I want to remain fresh every time. I want to be better each and every time.

Your career began as a young adult. How different do you think things would’ve been had you started when you were in your 30s, 40s, 50s…?

I started young in my late 20s. I was lacking in certain respects because of that, but I was full of passion. I don’t think I was making “real” movies, but fun and entertaining ones. I make the kind of movies I make now because that comes with age. Movie equals age and experience. A movie can only be as good as your age. If you’re 40, you can’t make a movie about someone who’s 60 or 80 years old unless you’re a genius, and even then, it’s extremely difficult. Someone who’s 40 can’t go back and make something about someone who’s 20 years old. A movie is your age.

How do you feel about looking at movies as a conduit for social or political change?

Film has great influence on society, so I want to contribute bright and healthy movies. In the beginning, I wanted to make fun and entertaining movies for society, but, again, everything changes as you age. No one can consistently do that for 50 years: “I want to entertain people!” I would get bored if I made the same thing over and over. War movies show us how inhumane, impure and poor we become, but we can’t keep doing that movie after movie. That’s when I started wanting to make more artful movies. Some directors can try to change society through a film, if they don’t shoot as many films as I did. I, on the other hand, made so many movies that contributing to societal change was maybe unintentional.

Just to be clear, my answers are not absolute. It’s my own personal insight based on experience and I’m not always right. I lived through big wars and under a lot of government oppression. People had no right to express their opinions. When the government collapsed and the war ended, censorship was lifted and movies improved. Korean people could finally show their passion, personality and color. The source of Korea’s big energy shows in things like K-pop and the Red Devils [official fan club of the South Korean national soccer team]. This is a great culmination of liberation, freedom and happiness coming out, which is also found in the movies. Now we can finally compete with American cinema.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments