Hitherto a merchant of extravagant fantasy, [Hayao] Miyazaki's depth of imagination defies classification other than his own brilliant mind.

A new feature film from Hayao Miyazaki is always a cause for celebration, even if it’s his last. The master craftsman of hand-drawn animation has managed to achieve status as one of the great filmmakers of his time and set a high-water mark of style that is meticulously observed and imbued with a rare generosity of spirit. His distinctive visual sensibility has garnered comparison to the titan Walt Disney fairly early on in his storied career. Hitherto a merchant of extravagant fantasy, Miyazaki’s depth of imagination defies classification other than his own brilliant mind.

The famed animator spoke frankly about his decision to leave the directing chair in a NicoNico streamed press conference, saying, “I know I’ve mentioned retiring many times in the past, so I know that many of you might think, oh again. This time is for real.” Earlier this month, Miyazaki released an official statement to better explain the reasoning behind his retirement. He went onto describe how his films continue to take longer and longer to produce—his latest, The Wind Rises, took five years to realize—and at that rate, he pointed out, “the studio can’t survive.”

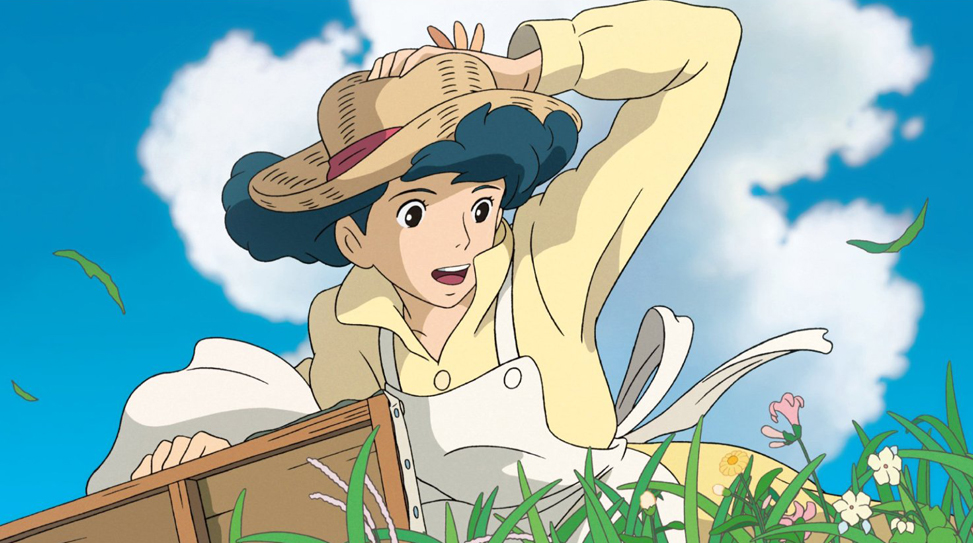

A socially astute portrait of Japan between World War I and World War II, The Wind Rises concerns a far darker subject matter compared to Miyazaki’s previous ten efforts for which the 72-year-old visionary is internationally revered, including Princess Mononoke, the Oscar-winning Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle and Ponyo. The elegiac historical drama opens in 1918 as a young Jiro Hirokoshi’s (based on the chief engineer of the Zero fighter jet) ambitions of becoming a pilot are thwarted by his own myopia and recurring dreams about Giovanni Caproni (the Italian aviation pioneer), who persuades him to design planes rather than fly them. Caproni recites French poet Paul Valéry from which the film takes its allusive title: “The wind is rising. We must try to live.” The wind is a portent for the disasters anchoring the movie: the 1923 Kantō earthquake, which leveled much of Tokyo and Yokohama leads to Jiro’s encounter with Naoko, a woman he rescues from a train crash who later re-enters his life; Japan’s plunge into World War II, and a deadly tuberculosis epidemic paving Jiro and Naoko’s road to ruin.

The Wind Rises is arguably Miyazaki’s most grown-up effort—don’t go into this expecting an abundance of moving castles, midnight cat-buses and a menagerie of adorably bizarre sidekicks. And if the film seems like a particularly personal project for the filmmaker, it might have to do with the fact that his father operated a factory producing rudders for the A6M, which instilled in the young Miyazaki a lifelong fascination with flying machines, both real and imagined. The Wind Rises is no doubt an impressive film that only a filmmaker of Miyazaki’s caliber could fully realize, but he will surely be better remembered for his other flights of fantasy.

The Wind Rises will open for a week in New York and Los Angeles for an Oscar-qualifying run in November with a U.S. release to follow on February 21, 2014.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments