There is no ‘best’ way to do things. It’s a question of how much you do it—whether you do it a hundred percent or not.

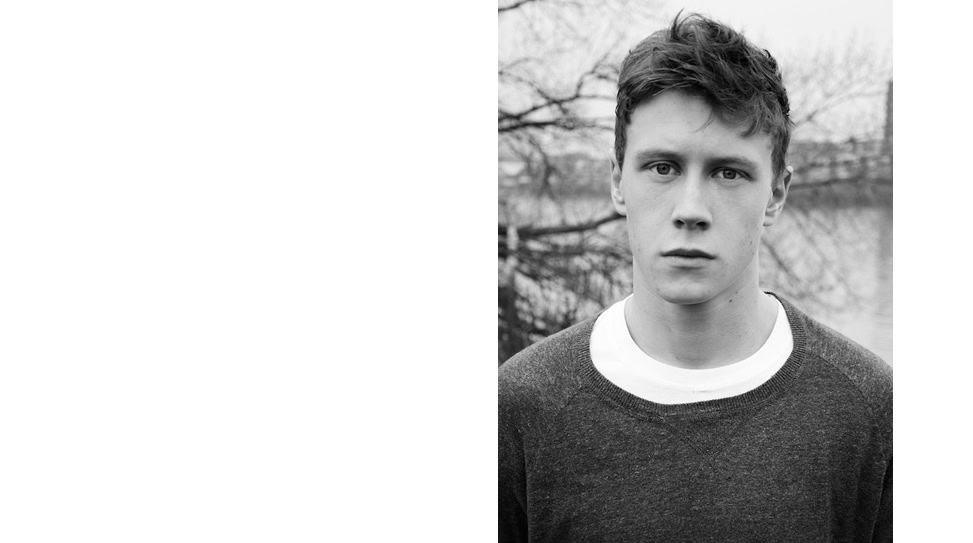

Awards season is a total circus—dazzling and overlong, providing ample opportunity to bandy about your favorite artistic achievements of the past year. With the end of each cycle, a new one begins, but for someone of George MacKay’s caliber, it’s not the end of anything at all. Hot on the heels of his breakthrough role in Sam Mendes’s “one-shot” war epic and Oscar frontrunner 1917, the 28-year-old British actor is clutching a rifle again, delivering another performance that warrants a double take—he’s game—and further signaling the arrival of our next, choice leading man.

You’d forgive MacKay any bemusement at being called an overnight sensation. He didn’t just pop out of the woodwork last year appearing as Lance Corporal Schofield in 1917. In fact, he has been at the craft professionally since the age of 10, plucked from school by a talent scout and cast as one of the Lost Boys in P.J. Hogan’s 2003 live-action adaptation of Peter Pan. Where armed conflict is concerned, he had endured the First World War twice before (Pat O’Connor’s Private Peaceful, the TV miniseries Birdsong), the Second World War just the same (Edward Zwick’s Defiance, Tim Whitby’s The Best of Men), and a tour of duty in Afghanistan (Dexter Fletcher’s Sunshine on Leith). And while 1917 is what put him on the proverbial map, MacKay had another film in the can waiting to unspool—Justin Kurzel’s True History of the Kelly Gang.

Based on the Booker Prize-winning 2000 novel by Peter Carey, True History of the Kelly Gang is the latest attempt at telling the story of Ned Kelly, the legendary bushranger—Aussie slang for rural outlaw—and the gang of cross-dressing bandits he cobbled together to terrorize his oppressors. Like the book, Kurzel’s vision of an unforgiving backdrop of 19th century Australia is a fanciful mix of fact and fiction, chronicling Kelly’s short, tragedy-riddled life from the age of 12 living under the iron rule of the colonial English (played by newcomer Orlando Schwerdt before MacKay takes over) to his final date with destiny 13 years later. Kelly was fueled by his ravenous appetite for revenge until his very last moments, sentenced to death by hanging.

Kelly is a polarizing figure previously portrayed on screen by Mick Jagger and Heath Ledger. These are no small shoes to fill, but what MacKay brings is his own brand of punk energy to Kurzel’s rendition, in what turns out to be the best of the three attempts to tell the story.

Anthem reached out to MacKay at his family home on the Isle of Wight, where he’s currently riding out the pandemic, for a chat about acting and the paradoxical nature of time in filmmaking.

True History of the Kelly Gang hits Digital, On Demand, and participating Drive-Ins on April 24th.

How are you doing over there on the Isle of Wight?

I’m doing okay—thank you! I’m blessed to be in the position I’m in at the minute, to be a part of all of this. I’m with my family. We have outside space where we are. I can’t complain. To be honest, I’m just trying to keep a working day as usual. I had a project that I was in rehearsals for before the lockdown happened that we’re hoping to get back to, and a lot of other things, which I have always put on the back burner for other reasons. Now having this quarantined time, I’m trying to be as proactive as possible and orchestrate my days, to give myself a working day from the morning til the evening. Also, I’m taking the time to just kind of relax and catch up on things, watching and reading. It’s about trying to stay active as much you can in certain confines, but by the same token, we are afforded more time than we’ve had, too.

Not that I needed any more evidence of this, but you’re that reliable actor. You really go there with this Ned Kelly role. I wonder if it’s one of those things where a part looks incredibly daunting and brutal, and so that makes you want to try it on that much more.

Yeah! To be honest, the interpretation of the film and the interpretation of the character we wound up with was informed by the first audition actually. When I first read the script, that came with quite a down the line reading of Ned. I wanted it more than anything because of the possibility of the character and the possibility of working with Justin [Kurzel], and it was that audition with him that just completely flipped it on its head—my understanding of the character, the depth of it, and the psychology of Ned. It kind of freed up this interpretation as well. I think I was intimidated at first by the idea of being this symbol of Australian culture, but the way the focus of it was to play him as his own man, rather than the idea of a man in any kind of relationship to the kind of legend Ned Kelly was, allowed me to understand the irony of playing against that. The role came at a time in my life where I was so hungry to have an experience where I could really immerse myself more than ever into a role, and that’s how Justin works. I think Justin relishes in working with people. He offers you the opportunity to commit in that way, and I sort of had the means and the wants to do so. It was a wonderful thing.

I would agree that you were in capable hands. Justin doesn’t hold back, either. I remember his movie The Snowtown Murders. It was a frightening watch. I always wondered what kind of a filmmaker Justin might be. I imagine this intimidating figure, which is probably not true.

[laughs] It’s funny because, similarly, Snowtown for me is the most affected I’ve ever been in the cinema. I remember waking up sad the next day, just being blown away by the film. As a filmmaker, he’s just amazing. Justin is quite intimidating as a man. He has this real intensity about him. He’s a big man, too, and he has this big beard. There’s this real intensity, but mixed with a real sensitivity as well. I think that sensitivity is what he’s hungry to explore. I know enough about Justin’s interpretation of this Ned Kelly story, but I think it runs through all of his works. There’s an intrigue in it or an understanding or just a want to explore the way that polar opposites actually stand back-to-back and, therefore, are so close. I wouldn’t want to misquote him and get him into trouble, but… [laughs] I remember Justin saying one time, “The feelings that you get from making love and fighting are kind of the same.” He thought they’re sort of equivalent and parallel, the way in which you’re feeling physically—the way your heart pounds and your blood rushes—and the excitement that you feel emotionally. And yet, what those two things mean on the outside as actions are the absolute antithesis of each other. The way that two absolute opposites can coexist within the same world of feeling is, for me, kind of fascinating and also true to life. We’re quite literally going in dresses in the movie, and that with the hyper-masculine toughness, there’s a kind of emotionality that comes with that. There’s a sensual nature to being either sex. It’s a beautiful, murky, and passionate world Justin exists in. As a director, he has an amazing comprehension of the way in which you can subvert an outside understanding of something by giving it a completely different, yet completely truthful, context underneath.

I remember the very first audition I did, which is this scene between me and my mom [played by Essie Davis in the film]. I did the first reading of it and he just went, “No, no, no, no, no. Okay. Right.” He got me to look at the lady I was reading with and said, “Put the script down and tell her everything you think is beautiful about her.” Immediately, that opens you up emotionally. I told her how I felt about her eyes, her lips, her neck, and just how beautiful I thought she was. He said, “Do the scene, but you’re not mom and son. You’re sort of on a first date. You’re trying to figure each other out. Are you making her laugh? Is that a good laugh? Are you making me laugh? Is this a test? Is it going well? What is this?” It’s this flirtation, and this smiling back and forth. Then he said, “Now deal with the words in the scene.” Suddenly, we were playing these two people on a date. He knew that was the entry and the relationship between those two people, which felt absolutely true. When you stack on top mom and son, it gives it this whole other flavor and a double understanding. Justin is a monster at that. Also, in reaching that double understanding, he really wants you to feel it properly. He wants you to properly commit to that feeling, be it in a physical and literal sense or emotional. He doesn’t cut corners basically.

The film is imbued with this incredible punk energy, which I understand Justin intended from the start. It really captures the spirit of these young men who are at once angry, ambitious, and confused. When you’re given homework from a director, in this case Justin telling you to form a punk band with your co-stars and play a real gig he booked for you in Melbourne, do you take to that assignment trepidatiously?

Oh yeah! I think when we sat down we were all like, “Oh my god.” [laughs] But in the end, you do take to it enthusiastically because Justin commands respect naturally. Before he’s even asked you what to do, you feel hungry to do it. He creates such a commitment to the project because he’s a great director. You already have a respect for his work and, therefore, you grow to respect him. And the fact that he’s so inclusive as a collaborator makes you respect yourself. You just want to do everything as best as you can and give a hundred percent. In a sense, it’s actually about knowing that there is no “best” way to do things. There is just the way that you do it. It’s a question of how much you do it—whether you do it a hundred percent or not. You know that Justin is going to approach his work a hundred percent so that just makes you want to meet him where he’s at.

I remember reading that you had six months of rehearsals on 1917, and with Kelly Gang, there were a lot of false starts, so consequently, you wound up with much more prep time. You once said that “time equals understanding.” Do you feel that it’s more often the case that time is not on your side?

For sure! But I think all experiences are valid. I don’t know if there is one “right” way of doing it because there is also something to be said about the immediacy of jobs. When Kelly Gang didn’t happen the first time because the money fell through, I came back to the U.K. and did one film called Nuclear. We shot the whole film in three weeks with one day of rehearsals. There’s an energy to the making of something like that. Six months with Sam [Mendes] was a whole different kettle of fish. We were choreographing the entire film because, essentially, there wasn’t a conventional edit. All those experiences teach you different things. That said, with Kelly Gang, I was lucky enough to be in a position as circumstances unfolded where I could get that extra time, and I wanted to get that time. When we actually came to shooting certain scenes, we’d been rehearsing for months. With the scene between Sean [Keenan] and I where we’re laid together in the snow on the mountaintop, we’d rehearsed that for weeks because we knew it was coming on later in the shoot. Then when we came to actually do it, Justin said, “Right. We’re being snowed off the mountain so we have ten minutes. We have one take of this scene. Go now!” And that’s the take in the film! So, in a sense, all those months and months give you an understanding to be ready to capture something. Ideally, we would’ve spent half a day on that scene. Time comes in moments. There are moments within moments, if you know what I mean. It’s almost a year devoted to Ned for me, but some of the most profound elements of that year happened in 20 seconds. By the same token, you couldn’t get to those 20 seconds without the four-month process of getting there. Also, not to go every which way with this, but… [laughs] There are elements that aren’t essential within those four months. So you can’t really put a time on it. But I think sometimes time is understanding.

It’s often said that great acting looks as though you’re doing nothing at all because great actors make it all look so easy. That is to say, you make it look so easy. What do you find challenging if you strip everything back?

I guess what’s difficult sometimes is not letting your head get in the way. I think there’s a great satisfaction to orchestrating something and there’s a level of self-awareness in the mathematics of making something, but that ego can take you out of the moment. And knowing that makes you focus on trying not to focus on that. You’re in a vicious cycle of trying not to focus on that thing you’re focusing on! [laughs] You get stuck. So, in a way, clearing your head is one of the trickiest things. My dad said a lovely thing once when I worried about a scene that I’d done. I didn’t feel I’d done it well enough. I said to him, “I gotta tell you, dad. I’m gonna get this off my chest before I go into work tomorrow. I don’t really know how to function in this scene. I guess the only answer is to care less.” He went, “No, no, no. It’s not about caring less. It’s about trusting more.” That was a beautiful piece of advice he gave me. That’s the thing: find a way to keep caring, and also keep trusting. There’s of course that thing about failure also being good, but it’s really about just trusting in stuff and not being so caught up in too much of anything. Without being vague and noncommittal, it’s problematic to believe that the only way you can work is X or the only way that something is good is X, or that if X hasn’t worked in the past it can never work. It’s just about being fluid and not hanging onto the things too much either way. If you hang onto the things which you receive are good, you’ll wear them out, and if you hang onto the things that burn you, you’ll never do them again. Stay easy and gain knowledge. I think that’s the thing—probably.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments