When Pedro Almodovar and Quentin Tarantino crowned The Secret in Their Eyes as the Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards last month, it had us scratching our heads. Even the most distinguished film critics of film critics had so convincingly thrown down their bets, practically handing the golden statue to The White Ribbon and A Prophet in the many months leading up to the awards ceremony. So, why is it that so many of us got it wrong? Why wasn’t anyone talking about the Argentine film?

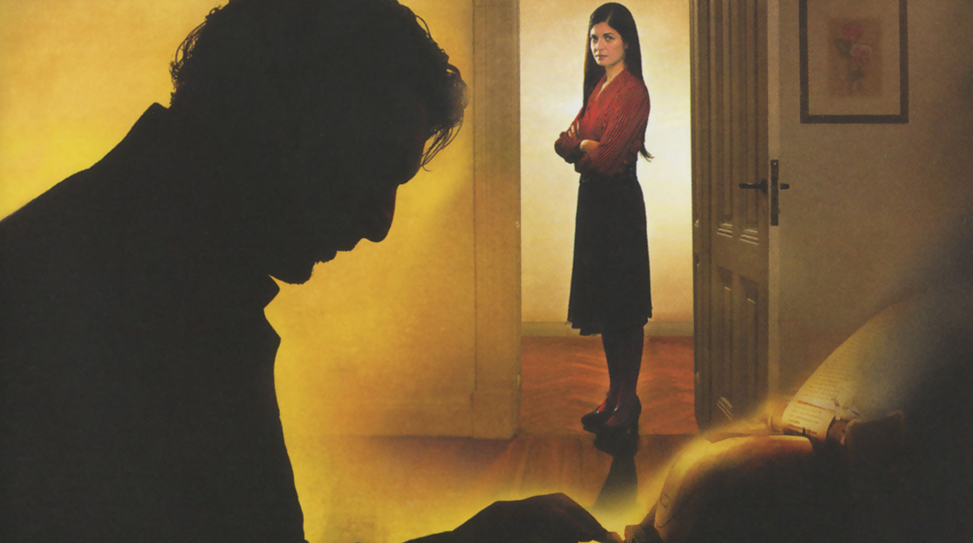

Juan José Campanella’s The Secret in Their Eyes follows Benjamín Esposito, a recently retired criminal court investigator who decides to pen a novel about an unsolved rape and murder case that has haunted him for 25 years. But Benjamín gets far more than he bargained for when his renewed pursuit of justice pits him at the center of a judicial nightmare and his own life begins to deteriorate.

This is a solemn and, at times, weighty message movie in which cinematic images of great suffering are mobilized in the service of ideology. Not to mention a treasure trove of moral introspection that pushes it well beyond the boundaries of the police procedural—a genre rendered purposefully prosaic in Campanella’s directing stints for “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit”. To top it all off, the film boasts one hell of an ending that, frankly, still gives us the heebie-jeebies.

The Secret in Their Eyes opens in limited release in L.A. and NYC on April 16 with a national rollout to follow.

First off, I want to congratulate you on your Oscar win.

Thank you very much.

I don’t mean to devalue your film in saying this, but there was a lot of buzz surrounding two films leading up to the Oscars and those were The White Ribbon and A Prophet. Were you at all surprised when you won?

I want to say something about that actually because it was a learning experience for me as well. Most of the predictions that came from the specialists were not based on the movies themselves, they were based on the awards that were given out in previous years and what other people were saying about the nominated movies. I knew for a fact that none of these people had seen my movie because we weren’t showing it outside of the Academy screenings. So, there was no way that you could’ve seen it unless you were in Argentina. Also, the Golden Globe results had a lot of impact on people’s predictions. But the Oscars are not a consequence of what happens at the Golden Globes. Based on what happened this year and also last year with Departures, people should start realizing that what the Oscar voters care about is only the movies themselves. They don’t give a shit if a movie won 15 awards at festivals around the world or if your movie just opened and no one saw it.

At the beginning of the race when we first got word of the nomination, I was very happy, but I was thinking that The White Ribbon was going to win. I didn’t think we had any chance at it. I just took it as a great honor being nominated and looked forward to having fun at the ceremony. Then, in the last ten days leading up to it following the Academy screenings, people were talking about my film on a lot of blogs and I started believing that I had a chance. At that point, I became a nervous wreck. [Laughs] If you look at the five nominated films, they’re radically different from one another. There’s an open-mindedness there in the voter’s selections, you would never see these movies together in any festival. And I love The White Ribbon and Michael Haneke as a director. To me, one of the biggest thrills was meeting him and spending time with him.

You were nominated once before in the same category for Son of the Bride. Maybe it’s a bit too early to tell what kind of impact your recent win might have on your future, but do Oscar nominations really open doors for filmmakers like they say they do?

I guess it’s like a patch that you can wear, but nobody’s going give you money to make movies just because you won an Oscar. There are as many people out there whose careers have ended the day they won an Oscar. [Laughs] I think the impact is indirect because it really makes a huge difference for the movie. It makes a lot of people who haven’t seen the movie to go track it down to see what all the fuss is about. If they like the movie, then maybe that will open doors for me. So, in a roundabout way, it could open doors. Also, since I won an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, it’s not like, “Oh, you won an Oscar? Here’s your next movie.” That doesn’t happen. Nominations are good for movies as well, but in terms of a director’s career, it ultimately means nothing.

The Secret in Their Eyes is a film adaptation of La Pregunta de Sus Ojos. What drew you to this particular novel?

I’ve always been a fan of hardboiled mystery novels. I don’t know what the film noir equivalent would be in literature over here, but we call it “novella noir” or “black novel” where I’m from. The problem I run into when I read most noirs is that I feel very detached from the characters; the characters always seem like two-dimensional literary creations rather than real people. The drunken detective, the lonely guy… What I liked about this novel is that it stayed within that genre, but the characters seemed very real. I didn’t feel detached from the characters at all. I had total empathy for them. So, that’s what I liked about it.

All in all, how close would you say this film is to the novel?

The novel was the basis for everything, but we added a lot of stuff to the film that’s very different. For example, Irene’s character is much more prominent in the film. She’s actually not related to the murder case at all in the novel, so we brought her to the foreground. We wanted everything to be based more in reality as well. The characters get scared for their lives. If they see a corpse, it affects them forever.

I read in one of your previous interviews that the big chase sequence that unfolds inside the soccer stadium was something that you added for the film.

Yes.

That scene is really impressive from a technical standpoint. The camera descends from the sky—going from an overhead shot into the cheering crowd—and ends on a two-shot of Benjamín and Pablo. How was that achieved?

We actually end on a close-up of just Benjamín. Everyone asks about that shot, it’s great! [Laughs] Obviously, there’s a bridge between the helicopter shot and the crane shot. There’s a digital bridge there.

It’s totally seamless.

Yes, it’s seamless. Completely unnoticeable even if you go through it frame by frame on a DVD player.

Why was it important for you to stage the chase scene during a soccer match?

One thing that we made more coherent in the movie is this idea that all of the characters’ actions are motivated by some kind of passion. They don’t track down the killer through forensics; they’re able to find him when they figure out what his passion is. Passion even motivates the crime in the first place, the killer’s perverted passion for Ricardo’s wife. The carriage of justice is because of passion. Everything is linked to passion be it a positive or a negative one. In the novel, they find the killer by chance and I wanted something more provocative. I wanted my protagonists to actually track him down. The one thing the killer could not relinquish is this passion for his favorite soccer team. I’m pretty sure Americans can relate to that—you would never betray your football teams! [Laughs]

I basically had five minutes to show these guys running after one another. If I had shot that conventionally, it would’ve been the same thing you’ve seen a thousand times on every TV show from the 50s on. And since everyone’s talking about this scene, I know it was a memorable moment. It puts the audience into the POV of someone who’s chasing the killer and that immediately generates excitement. If this were accomplished with a lot of cuts in the edit, it wouldn’t have been as effective.

Another great scene is the big payoff in the film’s final moments where you see the killer, all aged and frail, emerging from inside the makeshift cell that Ricardo built.

Passion drew Ricardo to lock the killer up for 25 years. His own perverted passion drove him to do this as a way of exacting revenge. He’s as much in jail as the killer is because he will never find happiness again.

Was it written like that in the novel?

The only difference is that, in the novel, Benjamín finds them both dead. He receives a letter from Ricardo years later that says, “This is where I live. Come and see me.” When Benjamín goes to see Ricardo, he finds his body with another letter instructing him to go to the barn behind the house. And he finds the killer’s body there. In that second letter, Ricardo also explains that he had kept the killer locked up for many years. When Ricardo developed a terminal illness, he decided to kill his prisoner and then kill himself. Benjamin buries them both and that’s it.

When Benjamín discovers what Ricardo had done with the killer, he turns a blind eye. Are we as an audience to believe that Benjamín supports this kind of vigilante justice?

First of all, I don’t see it as vigilante justice because this is a guy who was declared guilty as charged by the justice system. He was only freed by the executive power as a result of the corruption in that system. Ricardo was just executing the killer’s sentence, but on his own terms. He’s not playing the role of a judge. I believe that’s a big difference. Ricardo respects the judicial system more than the executive branch. I think my intention was clear in the film that he’s not meant to look like a hero. He’s not like Charles Bronson in Death Wish or something like that. It’s very clear that the killer and Ricardo both very much live in a cage. Although this is only said implicitly in the film, I think Benjamín at least thinks about what he should do about it. Personally, having written that character, I think Benjamín would go back and try to convince Ricardo to give himself up. But if Ricardo refuses, Benjamín wouldn’t turn him in.

I didn’t talk about this until months after the film came out in Argentina because I wanted the audience to make their own conclusions, but I’ll tell you now what my intentions were. The need for justice is deeply rooted in all of us and we will do anything to find it. If justice is not given its natural order, all sorts of perversions will take place. We experience it here in America like during the L.A. riots and the Rodney Kind trial. I remember this because I was living here at the time and obviously not supporting or encouraging it, but understanding where it’s coming from. It was coming from frustration over the gross miscarriage of justice. Personally, I would not turn any of the rioters in. I understand their need for justice. If you had told me that the killer in this movie had been declared innocent by the court and Ricardo goes and kills him in a scenario much like in that John Grisham movie with Matthew McConaughey… I’m forgetting the name.

A Time to Kill.

A Time to Kill! Then that would be vigilante justice. Ricardo is simply carrying out the sentence that the justice system provided. Throughout the entire film, we see Ricardo giving the detective leads and it’s only when he fails completely that he’s forced to take matters into his own hands.

I think we should also mention that the film takes place during a period of pre-dictatorship in Argentina.

Very good! You’re the only one who picked that up over here.

I think you have to read this film through its political prism in order to fully understand what’s going on.

The two years in which the film takes place, ’74 and ’75, are ellipses in the book—they’re not mentioned. The novelist of “La Pregunta de Sus Ojos” and I co-wrote the script and we made the decision of touching on these periods in the film version for several reasons. One of them being that it’s been so forgotten by our Argentine official history that most young people these days think the state violence began with the military. And this is not so. For young people to find out what really happened, it came as a surprise. I was also more interested in showing the corruption just as they were beginning to get verified. During the dictatorship, this wouldn’t have surprised anyone. I thought it would be much more interesting for the characters to see the truth for the first time.

You don’t need to read up on the history of Argentina to understand it. We wanted to contextualize what was happening in the film without it being all about that. If we said anything more, then we would have had to even more about the subject. You really just need to give the audience a little taste of what’s happening in the background. I always make an example of Casablanca. You don’t need to know all about World War II to understand who’s a good guy and who’s a bad guy. The details can ruin your enjoyment of the movie because it’s not meant to be a war movie. I’m comparing two completely different movies here, but the amount of context that you need to lay down works more or less like that.

What attracts you to the police procedural genre? The Secret in Their Eyes, certainly, but you also direct a lot of Law & Order episodes.

Special Victims Unit.

Right.

I’ve always loved procedurals. By the time I was 7, I had read all the Sherlock Holmes novels. Then I started reading Agatha Christie. In my teenage years, I graduated to the hardboiled novels. Even now, this is the kind of stuff I read while shooting a movie because it’s what I can concentrate on; I can’t read philosophy when I’m working. I love stuff by Michael Connelly as well.

You seem like an extremely versatile director. You have a colorful filmography to say the least. Son of the Bride, Strangers with Candy, Law & Order, 30 Rock, and now this film…

I really like moving around between doing comedies and dramas. As a writer, what I generate is more a blend of drama and comedy with varying percentages. I’ve made other films where the balance between drama and comedy was exactly the opposite from this film. Son of the Bride is a good example. As a director, I get to work with people like Stephen Colbert, Paul Dinello, and Amy Sedaris—it’s a complete riot! I don’t think I could personally write comedies like that.

Amy Sedaris is absolutely hysterical. That family is so gifted. What was it like working on 30 Rock?

I only directed one episode, but that’s another case. Working with Alec Baldwin, you’re always trying to stop yourself from laughing out loud and ruining takes. He’s terrific and it was a great experience.

What are you working on now?

I’m reading screenplays. So far, I haven’t found anything that I enjoyed. I need to put a closure on this movie first. It’s difficult for me right now to get back into the writing mode because that’s more about you being alone at home, waking up quietly, and being diligent. You’re a writer so you know what it’s like.

Of course.

I need to put this one behind me. There’s an animated movie that I’ve been developing for over two years now. We’re just now going into production with that.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments