When I watch my own movies, I only see the mistakes. I think every real artist has this problem. If you enjoy your own things, you must be crazy.

Michael Haneke likes to disturb calm waters. He pokes hives. He levels our sense of security.

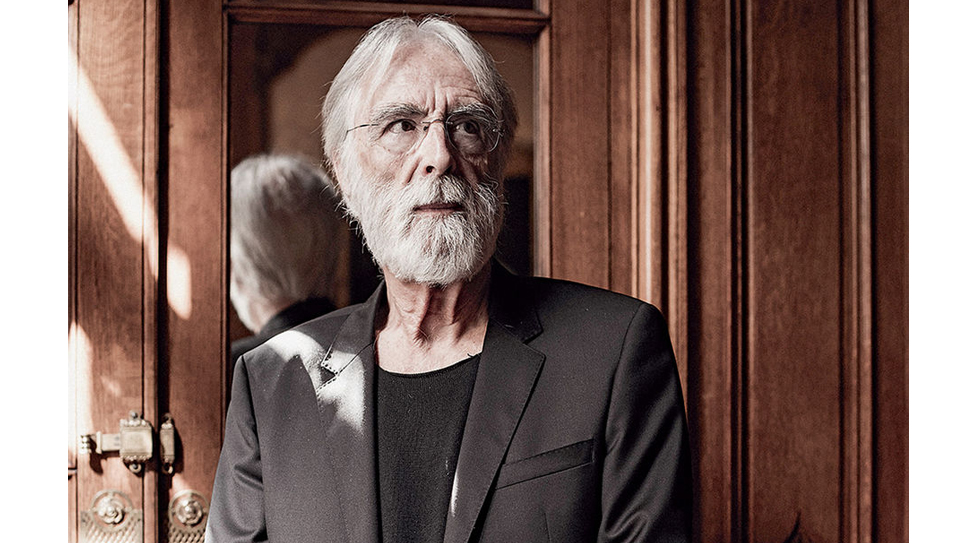

The two-time Palme d’Or-winning, 76-year-old filmmaker was born in Munich, but raised in and around Vienna by actor parents. After studying philosophy and heading into film criticism, he made his feature debut in 1989 with the typically uncompromising The Seventh Continent. His breakthrough came with Funny Games in 1997, about a family tortured by a pair of psychopaths at their summer vacation home. Haneke’s confessed argument against violence—a bold statement about how the indoctrination of mainstream thrillers has made violence acceptable in entertainment by crafting a motion picture that is anything but “entertaining”—is eerily at home to violence itself. “Who looks at the modern world with any degree of seriousness and sees much to be happy about? I’m puzzled by that,” he says. Haneke then filmed a shot-for-shot remake in 2007 starring Naomi Watts, Tim Roth, and Michael Pitt—another unconventional move by cinema’s cruel scientist.

This month, Anthem sat down with the Austrian auteur for a conversation in Vienna during his long-time producer Veit Heiduschka’s exhaustive retrospective organized by Filmarchiv Austria, which included a special screening of the original Funny Games in 35mm print to an intimate audience at METRO Kinokulturhaus. An obliging presence with ample wine at arm’s reach and addressing our curiosities in measured German, he also laughs more often than one might suspect.

[Editor’s Note: The following interview was conducted with the aid of an interpreter.]

There have been comparisons made between Funny Games and Benny’s Video—unsettling and confrontational earlier works that earmarked you as cinema’s cruel scientist. You also worked with Arno Frisch and Ulrich Mühe on both projects.

In many of the films I produced, there’s a main subject and that’s the case with Funny Games. The couple, [Ulrich Mühe and Susanne Lothar], were my favorite actors and I cast them whenever possible. As for Arno Frisch, he’s the son of my wife’s school friend’s brother. [Laughs] Yes, it’s true. I was looking for a very long time for someone to play this child [the titular role in Benny’s Video] and my wife said I should consider Arno. I told her, “Please, leave the children of friends out of this.” But after looking for an actor for months and when I couldn’t find one, my wife said, again, “Come on, have a look at him.” So we had a rehearsal and it was immediately clear to me that he was right for it, even if he had no experience. He had an arrogance about him.

How did the rest of the cast come together for Funny Games?

Like you usually cast, actually. You just know that certain people can play it well. When I was searching for actors for Funny Games, I got to really know Ulrich Mühe for the first time and that was when he became my favorite actor. It’s not easy to have them do something like this twice, but I can’t think of a single thing they could have done better. As for the boys [Frisch and Frank Giering], we were looking through agencies. It was very difficult casting the evil roles. Giering was someone young who was just coming out of acting school in East Germany. He became relatively famous on German television, but now he’s dead due to alcoholism. Many of the actors in this film are dead now—it’s very sad. I hope it’s not a bad omen for the others. [Laughs]

There was also the 1997 TV movie you directed, The Castle, also starring Frisch, Mühe, and Lothar together. Did that come before or after Funny Games?

It was before. I had known that Susanne, Ulrich’s real-life wife, was an actress and I admired her. I got to know her socially. So I told them they should do it together, and I generally don’t like having couples at work because I used to work with couples often and it’s hell. For example, scenes where I once directed Wim Wenders and Angelika Domhäuser—they became famous afterwards—were shot individually and it was wonderful. But as a couple, they were insufferable. It’s because, after rehearsals, they go home to practice their parts together. The next day, they come with their ideas all worked out and we have to restart from zero. It was the same thing with other couples. That’s why I said, “I’ll never do that again.” But Ulrich and Susanne didn’t work together in private. Their method was so different that this private agreement between them didn’t exist outside of work. It was working great. I actually wrote another role for Ulrich, but he died during scheduling. That was terrible for us and for Susie. She nearly had a breakdown. Now—she’s dead, too.

I recently spoke to directors who both have child actors as leads in their debut features. What was your approach to working with Stefan Clapczynski on such distressing material?

The most important thing is that the child is talented. It’s always very difficult when you cast children. The only talent you need as a director is to know whether an actor fits or doesn’t fit the role. If you have a sixth sense about it, there isn’t much that can go wrong. If the screenplay is good and the characters are well cast, it is very unlikely that the movie will fail. Although, it can. But if an actor has to play a lion, he’ll play a lion more or less well and it’s the same thing with children. A child can empathize without difficulty into a character and that’s what you can benefit from. You have to manipulate actors to get them to where you want them to be.

So it’s not any different working with a child for you.

This is clear. Students often ask me about my methods and I always tell them that there is no method because every actor is different. The most important thing is to empathize with them, that you know their fears, and there is a trust between you. If not, the situation with the actor becomes difficult. It’s all about fears. The director can hide behind the actors, but it’s not the actors’ fault. The director either cast the wrong person or he was unable to bring the actor to where they need to be. It’s a question of empathy. I come from an acting family—both of my parents were actors and I love them, even if they’re tiring sometimes. There is no other job that exposes you to that much. I guess musicians, too, even if there’s a difference between the two. A violinist leaves their violin at home when they go to a party, whereas an actor arrives at a party and everyone expects them to be as funny as they were in their last movie. They’re always at the center of attention and it’s a very demanding job. What I’ve recognized when working with young people is that every single detail is important. There are hour-long discussions about floodlights and that’s worked on for an hour. Then when it’s time to shoot, the actor can’t play. You have to give them space, a lot of care, and this possibility for organic development. It’s a characteristic you either have or don’t have as a director. You can learn it. You learn it by practicing. It’s like writing: you only learn to write by doing it. It’s just more difficult with movies and the theater because it takes greater effort. With writing, you only need a sheet of paper and a pen. Movies are a little bit more expensive.

Were there rehearsals on Funny Games?

No.

Really?

I tried it when I was casting the younger actors to find out if they were suitable, but usually, I don’t. I worked in the theater for twenty years or more. In the theater, they try, try, try again, and then it’s time for the premiere. Suddenly, there’s an audience and the show gets more exciting, but only because of the audience. In movies, if the actor rehearses something and it goes well, there’s no tension. In my opinion, it’s better to do that in front of the camera. I tell them what to do without rehearsing and we shoot. If it’s good, it’s good. If it’s bad, we correct it. I don’t like to shoot things repeatedly, although it’s sometimes necessary. I can mention two examples from Funny Games. The first is after the child’s death with the ten-minute long take. I explained it to them and told them to just try it and assigned them to their places. The first take was amazing. The second take was so bad that I had to interrupt and we tried it again. The other one is where the wife is restrained and praying. That is very difficult to play. We tried it again and again and again, until she was at her best. It was very exhausting for all of us, but there was no other way to do that.

Speaking of long takes, is that something you have in mind from the script stage?

Yes, it was easy with this movie because I always envisioned it that way. If you want to employ certain formal elements to fit the movie, then you have to find the motivations for it. I try to enable it as much as possible by knowing the motives already. For example, in the scene with the child’s death, we had to film the entire room in a wide shot because you can’t capture grief and despair in close-ups. You need to have certain respect for the suffering and that called for wide angle. Besides, it helps the actors if you shoot an emotional arc like that only once because it’s difficult to sustain that. I’ve also produced movies consisting of all long takes. It’s great for actors. They have to know the text, and if they do, they have a lot of opportunities.

How long does it usually take for you to write a screenplay?

The writing doesn’t take me too long. It takes a long time to come up with an idea. When I worked in television, I had this idea for a movie called Wochenende [German for “weekend”], about a family going to their country home to find a guy who just committed a crime hiding out in their home because it looked abandoned. A lot of the story was a series of coincidences. At first, I wanted to do this movie because I was young and I had only done a few TV movies. But the financing offered by Deutsche Filmförderung wasn’t enough and I didn’t know anyone. Then when I had to shoot a TV movie in Georgia, there was a revolution going on outside and I couldn’t leave my hotel. There were shootings and it was a very unpleasant situation. I couldn’t sleep because of the noise so I had to do something and it was then that I thought about repurposing this story to produce a self-reflexive movie about the presentation of violence in cinema. Writing has become a very fast process since then, but the construction is difficult. Writing is a pleasure, but the actual work of constructing a screenplay to make it work is not. You have to tell the story in a way that won’t bore the audience, and to do that, you have to consider cinematic rules. So it’s a lot of work, but once you’ve figured it all out, you can finally sit down and write it, which is the fun part. If the construction is right, the writing is very fast. If it’s not right, you are stuck in a scene that doesn’t work and you have to start from the beginning again.

How aware are you at any time of other films coming out and the impact they have on cinema, at least in a peripheral sense?

There’s no other way but to consider other movies. The mainstream world gets off on the consumption of violence. If you look at all the famous blockbusters, violence is presented in a way where you can consume it easily and you get the adrenaline rush without any consequences. I’m upset about that. Of course, the ‘90s was a time when those features were important, so you had to show people the position we were in. Usually, films aren’t involving, but it’s still the best medium for manipulation. What I wanted to show with Funny Games is that movies can transport you anywhere you want. You can interrupt the movie to say, “This is only a movie—we know that.” But after five minutes, I have you again. I give you this chance to drop out five times, but you don’t want to. You want to know the end. That’s what I wanted to show. It was great fun. [Laughs]

You received criticism for that as well. It’s unconventional, to say the least.

For me, the film’s premiere was my greatest success. There were boos and bravos—it divided the audience. When The Piano Teacher premiered, we only got praise and I was disappointed. I should’ve been satisfied, but I got the feeling I did something wrong. Every time that something is good, something is wrong. You have to do it in a way that some people will get angry.

John Zorn’s score, the lack of score, the heavy metal… You’re particular with music.

As you see in the end, John Zorn is like a guiding theme—how can I say this?—from the evil. I’m a music enthusiast. I know a lot about music. For me, it’s a pleasure to select the music. In a realistic movie, music has no value unless someone turns on the radio or someone plays it. Also, I think music creates a sense of false excitement. If you watch any episode of Tatort, the commissar will get into his car and drive through the streets of Munch, leave the car, get in again… Nothing is happening except the music that’s playing over it. That’s what I hate. You should only use music when you know why you’re using it. In the case of Funny Games, the classical music by [George Frideric] Handel characterizes this family. John is clever. The heavy metal makes reference to heavy metal. The movie makes reference to action movies or thrillers. It all exists on the second level. So John was appropriate. At first, I wanted to use another type of music, but it didn’t have enough impact. Someone on the crew brought up heavy metal and it was perfect.

It’s unexpected.

Yes, of course. It was funny. The most interesting thing are those moments. When you choose the music and see how scenes work to different music, it’s a very beautiful part of the process.

If I can get super specific for a moment, you have the scene towards the end where neither parents know how to dial the police. It was really puzzling to me. What was that about?

I didn’t know the police’s phone number, either. I know the American police number since 9/11, but before that, I didn’t know that. In America, everyone knows to dial 911, but I didn’t. And I haven’t had to call for the police so far. [Laughs] It’s the same with the fire department. I have the number saved in my phone because, by the time you look it up, the house has burnt down.

How do you feel about Funny Games nowadays? Are you more or less self-critical?

There’s always something you could do better—that’s why I don’t like watching my own movies. I don’t know any musician who likes to listen to their own songs. When they listen to their own stuff, they only hear the mistakes. When I watch my own movies, I only see the mistakes. I think every real artist has this problem. If you enjoy your own things, you must be crazy. So I see the mistakes and I get annoyed about that, but I have to accept them. But I wouldn’t change anything in retrospect. Of course, over time, you get more clever and say, “I could have omitted this,” but there’s no movie that I’m embarrassed about. One movie didn’t succeed completely because I was wrong about the casting, but I won’t go into details. I don’t watch that movie at all. You see—you have to accept your own mistakes and that’s what I tell students. You’ll watch your movie twice in your life: you’ll see it during color correction and you’ll hear it during the sound mixing. After that, you’re never going to watch it or hear it again the same way because in every cinema it will look and sound different. You’re going to be frustrated by that every time. So in addition to your own mistakes, there are so many others in every screening. That’s something you have to bear when you’re doing this job. It’s worse in theater because they work for eight weeks on a play and every evening the performance looks different. One day, the actor does it well. The next day, the actor’s parents die—it’s uncontrollable. With movies, you can control it better. But when actors are done and the film is being cut, they already know where they weren’t successful. That’s part of it. If they didn’t suffer, they’re idiots for enjoying every nonsense they did.

Did you leave anything on the cutting room floor?

Yes, but very few scenes. There was a chase scene between the little boy and the two guys. There was also a fight scene that we had to cut out. These are delicate things that happen. Overall, the movie is what I intended it to be. Of course, it was only possible thanks to these amazing actors. It could be the same screenplay and me directing, but if I didn’t have these actors, the movie wouldn’t be half as good. We directors owe everything to actors.

What did your long-time producer, Veit Heiduschka, think about making Funny Games?

He said, “Let’s do it,” like to all of our other movies. [Laughs] I’ve been working with him now for thirty years. I never had any difficulty in doing what I want to do. If he didn’t like something, I did it anyway and he was okay with that. The collaboration has been good for both of us. He’s a kind person. He’s not as hot-tempered as me. Sometimes we quarrel, but five minutes later, we make up. He’s a likable producer. It says a lot about him that he has a wonderful crew working with him that’s not a constant rotation of people for thirty years now. They know how to work with us as well. The most difficult situation about producing a movie is when there’s an executive producer who doesn’t understand our dynamic. Michael Katz, Veit’s producing partner, is the best executive producer that I know. I couldn’t have done many scenes in The White Ribbon without someone like him. It’s crucial to pull a movie together with the same kind of intensity from the top. We’ve had mutual success and enjoyed long-term, pleasant work.

What was the casting process like for the Funny Games remake?

Finding the cast wasn’t that difficult. Well, maybe a little bit because I originally had a different concept with Philip Seymour Hoffman in mind. He didn’t do it because he had just reached the level of Oscar success and didn’t want to do it. Tim Roth was—I don’t think he’s a bad actor, but he wasn’t my ideal choice. I absolutely wanted to have Michael [Pitt]. When we started casting, all the young and well-known actors came. It was all a cliché. Then someone told me about Michael. People told me, “He’s a drug addict and a terrible person. Keep your hands off him,” but he was actually better than all the others in rehearsal so I chose him. The producer was very angry—it was great. The movie was certainly difficult for the actors, as well as for me, because it was shot-for-shot. When everything is fixed in the way it needs to be shot, you don’t have much wiggle room. I told them not to watch the original movie because then you run the risk that they’ll just walk in the footsteps of other actors. But of course they all watched it. [Laughs] In the beginning, it was difficult for Naomi [Watts]. In America, the actor has more responsibility because the director is sitting far away, chatting with the cinematographer. I know from many actors that they’re not used to the director interfering in every scene. So she felt like a marionette, but I told her, “You won’t believe this, but I also told Susie to turn around here and when.” Naomi was overwhelmed.

Did you have any fun remaking Funny Games?

It was difficult for all parties. It was difficult for me because the production involved a bunch of idiots, in contrast to the production in Austria. Here—we finished the film easily in six weeks without any overtime. There—we barely finished in eight weeks. It was slow and tough and expensive. Every day, there were fifty cars for no reason and you struggled to get to set. It was not a pleasant experience. My wife was there, too, and when I came home, she thought I was too old for this because I was exhausted all the time. But first of all, it was the production’s fault—not the actors. It was sometimes difficult with the actors, but they were effective and fun to be around. The only way productions seem to work in America is if they work at a high level—at the blockbuster-level—where they shoot a minute a day and take a very long time.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments