I remember realizing that anything I said to defend myself would just make the situation worse, so I had to stay quiet, although I was seething with the feeling of injustice.

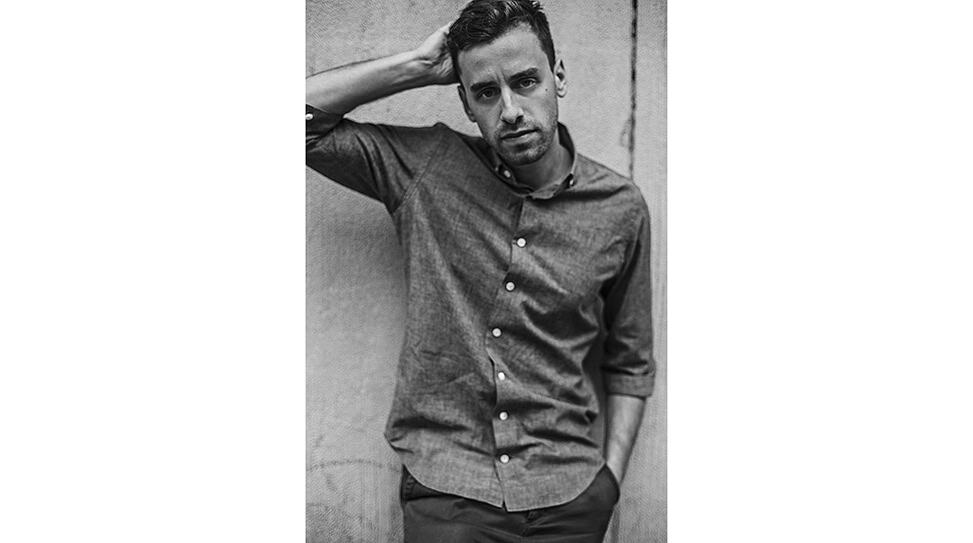

Matt Sobel’s debut feature Take Me to the River is a quietly unsettling Southern tale that isn’t Southern at all, actually. It’s a Nebraska-California culture clash and sexual abuse story confined and contained in a single family, on a family farm over a reunion celebration one weekend.

Logan Miller plays Ryder, a gay California teen. En route to his mother’s family farm, Ryder and his parents discuss whether to announce his homosexuality at the get-together on the way. He reluctantly agrees to downplay his being gay, although his conservative relatives pick up on it from his flashy short shorts and sunglasses when they get there. It’s when Ryder’s nine-year-old cousin asks if he’ll come play with her in their barn that, before long, she comes screaming back to the house with a bloodstain on the front of her dress and the real drama starts to ensue. Everyone treats Ryder strangely. With his cousin bound in some whispered conspiracy with her father, she takes Ryder to a local river, involving him in strange play that uneasily echoes the sexual ambiguity of the barn incident earlier. Ryder takes most of the film to realize that what’s transpiring relates less to him and more to a festering family secret that he has, in fact, wandered into unknowingly.

Take Me to the River is now playing in select theaters in NYC, and in L.A. on March 25.

The most obvious question I wanted to ask when watching this movie was if it was autobiographical. How did you relate to the material?

The location and setup of a family reunion are entirely real. The farmhouse in the film is the very house my mother grew up in that I’ve been visiting my entire life. I tried to capture the atmosphere of my Nebraskan experience as accurately as I could, but the drama is entirely fictional. About six years ago, I had a dream I was falsely accused of something terrible at one of these family reunions. Upon waking, I couldn’t remember what I’d supposedly done, but I did remember how uncomfortable it made me feel. I remember realizing that anything I said to defend myself would just make the situation worse, so I had to stay quiet, although I was seething with the feeling of injustice. My first goal in setting out to write this film was to capture that visceral sensation.

As a straight man yourself, why was it important that Ryder, your protagonist, is gay?

The most important thing to me was his feeling of helplessness in a foreign environment, and nothing makes me feel less in control than when the one thing I always have to lean on, my ability to make a logical argument, is taken from me. Ryder finds himself in a precarious situation where his sexuality, which would exonerate him in California, might only serve to further indict him in Nebraska. Both homosexuality and pedophilia might fall under the umbrella term “pervert.” The rules of the game have changed and he finds himself trapped and without protection.

What can you tell me about your childhood growing up in Nebraska?

I grew up in San Jose, California, but I visited Nebraska every year growing up. Contrary to what you might expect from the film, I always really enjoyed my time there. None of the characters in the film are based on my real family, but if there’s one aspect of their demeanor I did borrow, it came from a saying I remember my grandmother often using: “If it don’t scare the horses…” This idiom, which originally comes from the trial of Oscar Wilde, and meant something quite different in that context, means in Nebraska, if it doesn’t disturb business as usual on the farm, why talk about it? [Editor’s Note: Wilde’s original quote was: “I have no objection to anyone’s sex life as long as they don’t practice it in the street and frighten the horses.”] Essentially, keep your feelings inside. This burying of disagreements to maintain normality and cordiality is something I see in myself as well, and this film shows that potentially problematic strategy taken to an extreme.

Your fine art background shows up a lot in the film in unexpected ways. Why did you decide to move away from that into film?

I love that you feel that way. I am probably too close to see it. Truthfully, I never intended on being a fine artist. I decided early at about six years old that filmmaking would be it for me. I didn’t particularly like the film school environment, however, and so chose to make films all the way through art school. I imagine a certain amount of aesthetic sensibility and methods for unpacking meaning from story that we honed in art school found their way into this film. I did write the first draft of it while still in art school and the original title was embarrassingly academic sounding.

Did you have a difficult time choosing material for your first movie?

It kind of chose me. I don’t feel particularly in control of the ideas that come to me or interest me. I’ve tried exploring ideas that, on paper, made quite a bit more sense than this and always to frustrating results. Whereas this one, after the dream I had that I mentioned earlier, practically fell out of me every time I sat down to write.

What was the experience like being displaced to a remote place with a group of people when you were shooting this movie? I find that to be such a romantic idea.

It was at times romantic and at others challenging. All of our locations were remote and real. The shack we filmed in was inhabited by a raccoon family when we first arrived. The river was only accessible by a four wheeler and horseback. My hope is that the immersive, sticky, and sun-drenched atmosphere of the farm made it into the film. The community opened its arms to us out-of-towners in-between shooting hours, however. There was one watering hole in the small town we stayed in and that became our headquarters while in production. People from our team would regularly go horseback riding, fishing, or skeet shooting with the locals during off-hours. I feel like it was a unique experience for all involved.

How much do you think about the possible controversial nature of this when you’re writing?

Not at all, really. It would probably be quite crippling if I did. I think that you first need to get the idea out before judging it in that way. We did, however, think about and debate the topic extensively during the editing and test screening process. We probably made 50 versions of the scene at the river, shaving a second here, a second there, and showing it to the audience again and again. In the end, there will always be people on both sides. Some say we should be more explicit, some less, and some people say we shouldn’t have even touched this subject matter at all.

How do most audiences react after watching your movie?

It usually takes people a couple minutes at Q&As to formulate a question, but when they do, it almost always becomes apparent that everyone in the audience saw their own film. One person is convinced that the mother abused her brother when they were children and another just as emphatically the opposite. They sometimes end up in a debate, and while this might make another storyteller nervous, I find it quite rewarding. We deliberately left negative space in our film for people to bring their own suspicions, fears, and assumptions to the table. We invited the audience to co-create with us. The real story isn’t on the screen, it’s unfolding inside of the heads of everyone in the audience, and honestly, I’m more interested in what you think than what I think.

Were there challenges you faced that you maybe didn’t anticipate when you were making it?

Going into the film, I felt pretty comfortable working with each of the actors one-on-one, or even in pairs. When we reached the larger family reunion scenes, however, and needed everyone to be giving spot-on performances within one long take, that’s when it felt like my head was going to explode. I’m not musically inclined, but I imagine it might bear some similarity to what a conductor feels, needing to listen to each musical line in a symphony individually and in harmony simultaneously, having to sculpt the whole by adjusting one note for one instrument at a time.

How did you find Logan to play Ryder? What did you like about him when you were casting?

I met him a year before we started shooting, and instead of a traditional audition, I did a hour-long improv with him where I played his mother and he had to come clean about the thing in his life he felt most ashamed of. What I was really looking for was someone who could comfortably occupy an incredibly uncomfortable space. Logan had done mostly comedy at the time, but I could tell from our first interaction that his natural instincts to turn excruciating silences into awkward almost laughable moments was spot on.

This might be such a random thing to ask, but how did you land on Ryder’s clothes? It’s so paramount to the character that I think you put a lot of thought into it.

As for the shorts and the sunglasses, those were mine. I tried wearing red short shorts to a family reunion as a sort of experiment to see how people would react or if they’d react at all. In the end, I drew a few looks but not much. It was definitely a less dramatic entrance than I’d hoped, which I found more telling about myself at that age than my family. Ryder is at that very specific age where he’s testing boundaries and almost hoping for an argument or a confrontation.

What are you writing now, or eyeing for your next film?

I’m working on an adaptation of the YA novel The Scorpio Races with Focus Features currently. It’s the story of an island off the Irish coast and the mythic Celtic horses that haunt the surrounding waters. It’s a big departure from Take Me to the River. I’m also writing an original fable that I’ve been working on for several years already. It’s set in China and follows two orphan sisters who are recruited by a state-sponsored athletic school to be trained as Olympic high divers.

I’m also interested in your taste as a moviegoer. What are your favorites in no specific order?

Murmur of the Heart by Louis Malle

I don’t think a more specific and sensitively observed portrait of a 14-year-old boy exists. Not to mention a mother/son relationship that truly defies description.

Safe by Todd Hanes

It has such an incredible feeling of dread and one of my favorite ambiguous endings.

Stalker by Andrei Tarkovsky

I can’t really describe what this film did to me, but it was singular, visceral, and unforgettable.

Badlands by Terrence Malick

It’s a mixture of murder and fairy tale adventure so beguiling it somehow makes a killing spree light fun.

Breaking the Waves by Lars Von Trier

Currently my favorite film, although it changes every few months. Emily Watson is shockingly committed. The film is a bodily experience while you watch it, and then a polemic argument when you pick it apart afterward.

The White Ribbon by Michael Haneke

It hit me about 30 seconds after the credits rolled that every audience member was a character in this film. I was a townsperson and my fears played just as large a role as any of the on-screen characters. It was a sort of mirror.

2001 by Stanley Kubrick

This is ubiquitous, I know, but deservedly so. Watching it is far more than a passive movie-going experience.

The Son by the Dardenne Brothers

The best example of an elephant in the room imaginable. It’s so simple, and yet, infinitely gripping.

Fitzcarraldo by Werner Herzog

I can’t decide what is more audacious: Fitzcarraldo pulling a ship over a mountain or Herzog making this film. In the end, they are the same thing. That’s why this film is brilliant.

American Movie by Chris Smith

This film is so much more than hilarious. Mark Borchart is inspiring. His relationship with uncle Bill is one of the most touching I’ve ever seen. Their spontaneous musings are often more poetic than carefully scripted dialogue.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

1 Comment

if this pizzza gate loving freak doesnt get destroyed by people like me who hate pedophilia and things that inspire it then there is no god and i feel more alone in this world then i already do which is impossible