There was a point where I had to be honest about the fact that I was spending so much time in the theater—that it really was increasingly central to my life.

The Gilded Age was a period of untold opulence. That is, for a select few. Industry came into its own on the backs of the Vanderbilts, the Carnegies and the Rockefellers, who made their names through shipping, steel, oil, real estate, and railroad empires. In America’s epicenter—New York City—the highest social circle was coined “the Four Hundred”: the number of guests Caroline Schermerhorn Astor could entertain, swanning about in her luxe ballroom. Mrs. Astor was the era’s undisputed queen amongst a handful of grand dames that ruled the city. Membership to this exclusive club was a matter of lineage. But that all changed once the nouveaux riches arrived, and Mrs. Astor’s MO was to adhere to unspoken codes in locking pretenders out of society thrones.

When Julian Fellowes’ The Gilded Age debuted in early 2022, new-money matriarch Bertha Russell (Carrie Coon) made her grand entrance as an imperious firecracker. Without delay, the old-money gatekeepers—chief among them Christine Baranski’s Agnes van Rhijn—smugly flagged Bertha and her railroad tycoon husband, George Russell (Morgan Spector), as interlopers whose attempts to join their dynastic ranks were misguided at best and offensive at worst. Driven by her preoccupation with high society, Bertha has continually proven that she means war, jockeying for her place with ruthless ambition. Among the more impressive aspects of The Gilded Age is how deftly Fellowes incorporates the Russells’ antihero arc into its stock-in-trade soap operatics.

The series’ new installments largely revolve around “the opera war,” a fight for patronage and prestige between the long-established Academy of Music and the upstart Metropolitan Opera House. Bertha, having been denied a box at the Academy, becomes the biggest supporter of the Met, throwing both money and her rapidly-increasing social influence into turning the latter into a palace she hopes all but the most stubbornly patrician Manhattanites won’t resist for long. Elsewhere, George, faced with the pressures of an organized labor movement at his Pittsburgh steel plant, and the impulse of the robber barons, of which he’s one, to crush workers in their demands for enhanced wages and safety protocols and shorter workdays, submits. But what is he hiding?

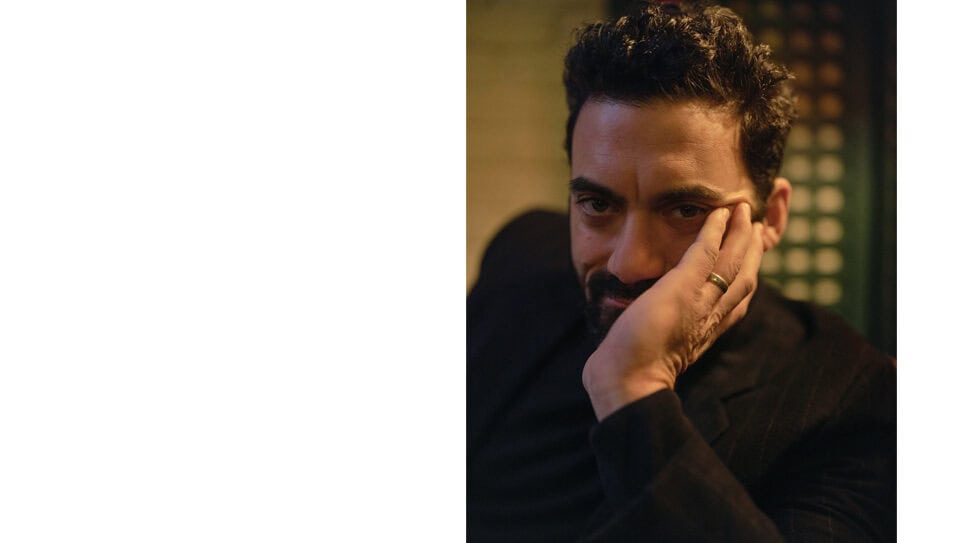

Anthem recently sat down with Spector to discuss the parallel between the show’s labor plotline and Hollywood’s dual strikes, his early beginnings, and buttoned-up decorum for our modern age.

New episodes of The Gilded Age airs Sundays on HBO and concurrently streaming on Max.

Mr. Spector, how are we doing today?

I’m good, I’m good. We had a long day of press yesterday, but it was nice and I got a good night’s sleep. It’s nice to be back at work. It’s nice to be back in the swing of things.

Congratulations on reaching an end to this very long strike. Was there a sticking point that felt most pressing to iron out, and are you happy with the deal overall?

I have to to say, I have been meaning to dive into the full deal and haven’t fully done it. But I think the major issue was a success-based residuals formula, and they did get a version of that. It feels somewhat complicated and it remains to be seen how exactly it’s gonna play out in the real world. In the same way that I think the writers felt at the conclusion of their strike, it’s a door that’s now open. It’s a conversation that’s now begun and it will be further engaged over the subsequent contract negotiations. On the issue of AI, the other crucial issue, it’s hard to predict how it’s going to be applied. But I sort of have a gut instinct. Studios, producers, et cetera, are driven by a desire to make a profit, and in order to do that, you have to engage with audiences. I just don’t think audiences want to see performances by fake actors. It’s like when you play a video game: you don’t really wanna watch the cutscenes. I mean, maybe I’m wrong, but typically, that’s not the most engaging part of a game. Watching movies, the thing you want to see is real emotions happening to people you know are pretending. That’s the exciting thing about performance. Maybe I’m being hopelessly naive: I’m sure there are ways that AI is gonna be used nefariously to take money out of our pockets. But I do think there’s something audiences just don’t want, and won’t respond to. I think that the deal we got was probably the best deal we could have gotten. I think we used the leverage we had and we got what we could get. And we’ll go back again in a few years.

This also feels like a good place to start in discussing The Gilded Age because, surely, the parallel between the dual strikes and the show’s current labor plot line is too neat to ignore.

Of course. I don’t think we quite realized how pertinent this storyline was going to be. Obviously, we didn’t know. I mean, I think people were discussing that there was the possibility of a strike, but it certainly wasn’t a certainty. One of the things I found interesting is, it’s been a long time since there was a labor action in our industry. I think for a lot of the tech companies that have entered the entertainment space, they’ve never really dealt with labor actions on a serious scale. For companies like Apple or Netflix, it’s sort of unfamiliar for them. And we are not used to thinking necessarily of CEOs like Ted Sarandos or Tim Cook as robber barons. Some of these people are sort of celebrated in the entertainment media press in an unambiguous way. Prior to the strikes, they were celebrated as being really innovative leaders and moguls, and then during the strike, you saw these anonymous quotes about executives saying they wanted to starve the writers out until they couldn’t afford their mortgages and couldn’t pay their rent. All of a sudden, this bitterly adversarial relationship between workers and holders of capital is revealed. On our show, it’s almost a more primitive form of capitalism, where the relationship between the worker and the boss is so much starker in a certain way. You can see that really nakedly. I think it was interesting to see just how acrimonious it got and how high the stakes still are in that conflict around organized labor.

As George, you’re on the other side of the bargaining table. And in the same way that people are rarely, explicitly good or evil, he has a degree of warmth to match a lethal guile in his business practices. We’re privy to that in his home life, in his united front with Bertha and in the way that he wants the best for his children. I wonder how he might’ve measured up to magnates like Carnegie and Frick whose badness was said to be a defining feature of that era.

Yeah, I think Carnegie and Frick are the analog for this season’s storyline: Patrick Page [in the role of George Russell’s loyal secretary, Richard Clay] mapping somewhat onto Frick and me mapping onto Carnegie. I think the Homestead Strike is the relevant analog. Frick and Carnegie’s men did fire on workers, but supposedly, Frick gave the order and Carnegie wasn’t in the country. There was a sense of divided responsibility so that Carnegie could keep his aura of the benevolent capitalist. I think to some extent that’s what’s happening here. What you’ve pointed out about George’s duality—his ruthlessness at work and his tenderness with his children and his wife—is the way the show found to watch his empathy evolve around this issue. Because it’s not just about meeting a representative of workers he respects—it’s going to the man’s house and seeing his wife and children, and realizing that the man’s children are not even really being given the chance to be educated because they have to go work in a factory when they turn 12 or 13. That’s, I think, in part what changes his mind. But I also think there’s just a hardheaded business rationale, which is that he knows he’s not gonna be able to come to a sustainable settlement with an organized worker body unless he gives a little. He’s gotta keep the factories running. Having constant open warfare with your labor force is not really in the interest of long-term stability. So I think there is, as you said, a certain guile there that maybe isn’t found in some of his more brutal peers.

One of the great pleasures of the show is that you’re not rooting for the same characters from episode to episode. You catch glimpses of a real soft spot, even in, at times, really detestable characters: Armstrong, Turner, and Agnes. George has his unflattering moments, too.

I think that’s a testament to Julian’s [Fellowes] writing. I think Julian is really genuinely interested in the full humanity of all of these characters. Sometimes you can really hear a writer who loves all of the characters that they write. Sometimes you can really hear their voice pop in each one of those characters. Sometimes I hear Julian’s voice clearly in Agnes. Sometimes I really hear it in the downstairs characters. And it’s often you. It’s when a character is given a line that’s just good sense. It’s when someone is seeing clearly, and that’s the kind of thing that brings you into sympathy with them. But yeah, I agree. Nobody stays a two-dimensional villain for long, even someone like Turner who we’re seeing have this florid, melodramatic turn, which is just delightful.

Yes.

In a certain way, by being juxtaposed against Bertha, there’s not really that much of a difference between the two of them. Bertha is maybe more composed. Maybe she’s been in the position she’s in for longer and maybe she’s a better strategic thinker, but they’re both people who rose from lesser circumstances to high status and power. I think because of that, we’re able to say, “You know, why not Turner? Why shouldn’t she get the right box at the opera?”

Julian does the upstairs/downstairs thing so well. You once called him a mosaicist—a mark of a great writer, I think. And his writing is high-style elevated. Did that take time settling into?

Technically, I actually find it quite challenging. When he did Downton Abbey, you have all these wonderful British actors who have played a lot of this sort of corset stuff. They come out of school and there’s just tons of that stuff on British television all the time so they’re playing period and they’re very comfortable in it. As an American actor, I haven’t really done a lot of that so there’s a challenge. You’re wearing these very constricting clothes. These people were extremely precise and constrained in the way that they moved and lived in a certain way. They were very proper and very ritualistic. But you also have to be a living, breathing human being. Balancing those things technically with the dialect and everything was definitely a challenge. There’s a learning curve there. But it’s been fun. It becomes a kind of ongoing game as an actor and it’s a pleasure.

I’m sure the constricting costumes has a way of yanking you up a certain way.

Oh yeah.

There are moments of watching period work where I so want to adopt that same kind of discipline and commanding presence. I hope to speak as clearly and matter of factly. You’ve spoken on this before: as an actor, you’re invited to use your “whole voice” and you speak as well as you can speak. These days, it’s like the best we can hope for is texting in full sentences with all the punctuations intact, where emojis are the worst offense and most offensive.

No, it’s true. If somebody uses punctuation in a text exchange with me right now, I’m like, “Are you upset? What’s going on here?” The way that we read tonality has really evolved. Obviously, the ways that we communicate have really evolved. My daughter has watched a little bit of The Gilded Age. She’s five and she really wants to play Gladys, of course. Sometimes at dinner, she’ll just start doing her Gilded Age voice, calling my wife [Rebecca Hall] and I mother and father, and asking us to pass the salt. [laughs] And I bring this up because, clearly, there’s an intrinsic pleasure there to the poise of these characters and the precision in the way they speak and communicate. Maybe there’s something in this time of very informal communication that almost transcends language itself. As you’re saying, maybe we do long for some of that grace and precision again.

So your daughter is five. Your first acting experience was around that age, wasn’t it?

Yeah, I was in a play when I was seven. That was my first theater experience.

How do you feel about your daughter pursuing acting if she so chooses?

It’s funny because she definitely has a little bit of that. I think all kids are completely in love with imaginative play. They just want to be other characters in imaginary worlds. She loves that. When we play together, we pretend to be characters from movies and things like that, doing all the different voices. That’s all she really wants to do. But she hasn’t yet said she wants to audition for anything. If that day comes, which it probably will, I don’t know… It would depend. I think in some ways being an actor is a wonderful life, but it’s also very hard. I think I would maybe like to nudge her more in the direction of being a generative artist as well—being a writer or a director or somebody who can sort of create it themselves. Not that it’s superior necessarily to being an actor, but maybe it gives you more of a sense of having, however loosely, a control over your life.

At seven years old, I believe that first acting experience was for a local repertoire company. It was a rendition of Christopher Durang’s Sister Mary Ignatius Explains It All to You?

That’s right.

Making progress in your life, you continued acting in high school. You studied acting at the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco after graduating from Reed College. On the surface, it would appear that you were in pursuit of acting in this unbroken, straight line.

I mean, you’re right. As you describe it, it definitely seems like a completely linear, coherent path. But honestly, it was always something that I did on an amateur basis. It was always something that I sort of thought of as a hobby. It was something I loved doing and I did it consistently in the same way I exercised consistently or did other things I wouldn’t have thought of as totally central to my life. I don’t know if I ever said this to anybody else: in conversations with myself, I was very committed to not being a theater major. I wanted to do something else more academic, more substantive, like political science or sociology or one of these other things so I could leave school and have a broader set of possibilities. But there was a point where I had to be honest about the fact that I was spending so much time in the theater—that it really was increasingly central to my life. As you said, I had been doing plays since I was seven years old. I went on to major in theater in college. I got a graduate degree. I did a film, which came to me in a very odd way. I hadn’t really gone out into the marketplace, auditioned, and gotten a job until I was at the Wilma Theater in a production of Sarah Schulman’s Enemies, A Love Story. It was the first time my agent called and said, “You got it.” It was this confirmation like, you’re not completely insane, there is potential here, and you could actually work in this business. I don’t think it was until then that I was comfortable saying, “I’m an actor.” I was really able to say, “This is what I’m doing with my life.”

In thinking about the nature of this business alongside high society as it’s depicted on the show, gatekeeping is an irrefutable through line. Old money versus new money. How difficult it is for new talent to break in. The politics that lie beyond talent. The games you’re made to play. Do you think a degree of ruthlessness is necessary, or at least helpful, in “making it”?

I think there is a ruthlessness you need, and I don’t mean ruthlessness in terms of stepping on other people. I think you have to be honest about your ambitions and about your desire to work above all things in a certain way. Acting is not a normal job. You sort of have to be committed to it before other things in your life. I think that’s what you have to be kind of ruthless about in order to be in the right place at the right time, to give yourself the opportunities you want. But I also think luck and good fortune are incredibly determinative factors in having a career in this business. I know so many talented people who just haven’t had the thing break the right way. This is a business that is so oversubscribed that you have to be good, you have to be prepared, and you also just have to be really lucky. That said, I have seen people who are ambitious to be superstars and they operate at a level that I don’t think is ruthless, but they go about doing that in a certain way. My ambition was always to work. I wanted to be a working actor. I don’t think I had a bigger fantasy beyond that. But I have seen people who clearly do and I’m impressed by it. I think there’s a way of operating where you just never let up pursuing that objective in trying to get where you wanna go.

I have this quote from you: “One thing about this business is that you have to take it as it comes. When I got out of drama school, I had all these ideas about who I was going to be and what kind of work I was going to slot into. You have to be flexible and go with the way you’re seen by the industry.” First of all, who did you want to be?

In college, my friends and I were really into experimental theater, especially the stuff that came out of the downtown scene in the early eighties like the Wooster Group. We were really into Robert Wilson and the Blue Man Group before they became this institutionalized thing, and all this stuff that came out of the Performing Garage and Locoq, the mime school that influenced a lot of devised theater. I thought I would find my way into that world. And this was all before I even got to New York that I was like, “Maybe I’ll get in with the Wooster Group or get in with Richard Foreman or some of these companies that are still going.” Then you realize those are hard to attach yourself to. Incredibly accomplished artists were involved with those downtown companies. It was as hard to break into that world as it was to break into the professional world. I got to New York and I was an outsider. I didn’t know anybody here. In a certain way, I had an agent and it was easier to get auditions for relatively commercial work so that’s the route I ended up going in.

How do you think you’re seen by the industry?

It’s changed so much over the course of my career. I think I have a slightly indeterminate ethnicity to my face. Early on, I played explicitly Jewish characters. I played Italians. There was a period where I was playing Russians. I did a play downtown that was critically successful called Russian Transport, and after that, it was nothing but Russians for a while. Honestly, whatever I had, I was grateful for the work, you know what I mean? In a certain way, being able to slot in as a character actor early on in your career is a blessing. But it was a while before I played anyone who wasn’t “some ethnicity” forward. I think that was a moment where I went, “Maybe I’m just an actor now. Maybe I have done enough wide-ranging work that I can slot into different places.” I think I have an Ellis Island face so I tend to play East Coast characters. I don’t get hired to do Midwestern farm boy parts. I mean, it’s just how you get perceived. What I hope is that I’m perceived at this point as someone who, if you hire me, I’m going to deliver. That’s all I really want.

I now associate you with having what you call a “resting period face.” These are your words, not mine! Is there more to come? What’s happening with The Gilded Age season three?

No idea. We are in total limbo. As I’m sure you know, it’s very hard to know what success is right now. What constitutes success for a show that comes out on both cable and streaming? What is the metric that’s telling you, “This is worth the budget”? We’re certainly not seeing all those internal metrics that Max or HBO are seeing. All I know is that it’s been really gratifying seeing that we have a pretty devoted and active fanbase. That’s really exciting. So I couldn’t put an absolute figure on how many people that is, but there are a lot of people who enjoy watching the show every week. I love our cast, I love doing this show, and I hope we get to do it again. You never know.

I chuckled when I saw that your Instagram bio reads “human decor.” It’s probably the most self-effacing and humble way of describing an actor’s profession I’ve ever seen. And I do wonder if it might actually feel like that sometimes, in a fleeting moment on set, especially on this show with your top hat, outsized by the out-and-out opulence of everything.

Absolutely. That’s very perceptive. That’s exactly right. Sometimes, especially on our show, you come to realize that, “Actually, the dress is the star of this scene” or “The incredible production design is the star of this scene.” Also, before I made that bio, I had watched my wife direct a film [Passing]. I in no way mean to diminish actors by saying this, but sometimes, as an actor on set, I’m thinking, “Am I grounded in this scene enough? Do I look okay?” I’m having all these self-conscious, bullshit thoughts and you’re hoping that the director is approving of what you’re doing. But the director is actually just looking at your body as a kind of geometric form in space sometimes, making sure that the light is hitting you correctly and that there isn’t a lamp behind your head. So that sense of being, that inner life of an actor, I think, is what really drives the quality of a performance. And sometimes, you are also just an object in the frame.

You bring up Rebecca’s directorial effort. Do you harbor directing ambitions of your own?

It’s something I have recently been considering much more seriously than I ever did before. I think some people really feel that they must direct a film. Having had such a front row seat to what it is to direct a film, it is really hard. It is really stressful and difficult. It goes on forever. The amount of problems that you’re asked to solve never ends. I do think you need to have some kind of imperative driving you forward. I’m still maybe waiting for the story where I go, “This is mine. I have to make this. I have to tell this story.” If I felt that, absolutely I would. Of course, there’s a part of me as I get older and my career evolves that says I should push out into these other aspects of the business. But there are a lot of people out there whose lifelong ambition is to direct a film, and that hasn’t been my path. So if I’m gonna do it and take one of those spots, I think I really have to need to do it. I haven’t felt that yet, but it is certainly possible that at some point I will. Martin Scorsese can’t make a profit on an art film right now. That’s crazy. What is the way to make a piece of American cinema a sucess when it isn’t backed by a studio or an enormous marketing department, and when it isn’t a horror film? I think we’re all trying to figure that out right now.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments