For someone who does what I do for a living, there’s no greater reward than hearing from individual after individual that they feel validated because we told this story.

The biggest sex scandal to hit the Roman Catholic Church might have stayed buried if not for one man’s sheer will to survive. Phil Saviano, the victim of sexual abuse by a priest in the ‘60s in Douglas, MA, was HIV-positive in ’84 and at death’s door with full-blown AIDS by the mid-‘90s. Bouncing back to health with a new dosage of meds, it’s around this time he chanced on The Boston Globe article about the same priest having abused another victim in New Mexico in the ‘70s. Soon, Saviano’s story was also reported on. A few years later, the Worcester diocese offered a settlement, and a confidentiality agreement Saviano refused to sign. When he became very sick again, his T-cell count—which hovers between 500 and 1,200 in healthy adults—stood at 1.

Since he refused to sign the agreement, Saviano was able to speak out about the abuse he endured so many years ago, founded the New England chapter of SNAP (Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests), sued the Worcester diocese to get access to key documents (letters by bishops) proving that the Church knew about abusive priests who had simply been moved around. Saviano became a de facto one-man investigative unit, ultimately providing paramount evidence that led to The Globe’s intrepid band of journalists known as Spotlight to break their Pulitzer Prize-winning series of exposés in 2002. The Boston Catholic diocese’s decades-long cover-up of sexual abuse of children had victims crying out for public exposure. The Globe’s Spotlight team provided it.

Tom McCarthy’s Spotlight recounts victims’ powerful stories of abuse. Saviano, now 63, is a key figure as portrayed by Neal Huff in the film. In one scene, Saviano holds up a childhood photo of himself at 11: “When you’re a poor kid from a poor family, religion counts for a lot. And when a priest pays attention to you, it’s a big deal. And maybe it’s a little weird when he tells you a dirty joke but now you got a secret together, so you go along. Then he shows you a porno mag, and you go along. And you go along, and you go along, until one day he asks you to jerk him off or give him a blowjob. And so you go along with that, too. How do you say no to God, right?” he says. The Spotlight team slowly build their case with each new lurid revelation. Nothing comes easy.

Spotlight is now playing in theaters everywhere.

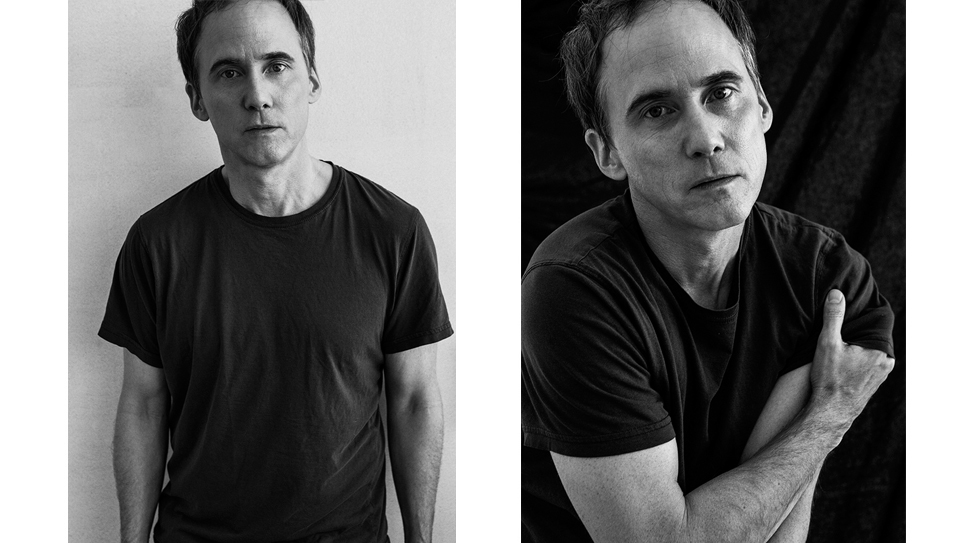

I would love to get a little background on you first. You’re originally from New York. What was your upbringing like, and how did acting become your life pursuit?

The thing that probably made me want to become an actor, besides seeing movies a lot as a kid, is that my mom would take me to a Broadway play every year. I think my favorite one was Doug Henning’s The Magic Show. I can’t necessarily say that’s what sealed the deal for me, but I think I was just a really bad athlete, basically. I think I was more into the idea of playing a sport, getting obsessed with something for a while, and then eventually realizing I wasn’t cut out for it. It’s almost like I realized there was something in my DNA that liked to really, really obsess about something for a somewhat finite period of time. As I look back now, I wonder if I was maybe just acting. I really sucked in hockey, but I was into it. It’s like, maybe I can turn this lame athlete desire to obsess about things for a short amount of time, ultimately, and turn to acting.

I find this association between sports and acting so fascinating because it comes up a lot, even with directors. I do wonder if it has to do with this predisposed desire to obsess over things.

Certainly with theater, it’s indeed like a sport. To do eight shows a week, I think it’s probably very close to a sport. There’s just something about the ritual of it and the group ethic of it that’s very similar to what I was doing as a kid athlete. But it was really a play at the end of high school when I was cast as McMurphy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which was a huge, huge film in my family. My father was kind of like growing up with an early ’70s Jack Nicholson. The famous scene in Five Easy Pieces in the restaurant when he sweeps everything off the table, that kind of thing was a somewhat regular occurrence in my family. There was a certain kind of appreciation of operatic rage, and my dad really held Nicholson up as a hero. So getting this play at the end of high school was a huge inspiration, and I realized that’s what I wanted to do.

Where did you attend high school?

I went to a Jesuit high school in the Bronx, Forham Prep, and they were very smart about how they taught Shakespeare. I remember watching [Franco] Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet in my sophomore year. There was something about being that age and reading all this dense poetry and then seeing these people—Olivia Hussey and Leonard Whiting in love—that everything galvanized. It’s like, now I get what that heightened expression of language is about. It’s connected deep, deep into the viscera. Then we’d watch Derek Jacobi’s Hamlet, and the famous Julius Caesar with John Gielgud and Marlon Brando. Somehow, it connected dense, impenetrable language to blood and guts for me. I had a very clear mission to want to do Shakespeare early on. After grad school at NYU, I think I did Shakespeare for about a year and a half. I played Troilus in Troilus and Cressida when they did it in the park, with a great cast and director. That’s kind of what got me going. And I basically hung out in the city a lot as a kid, even though I was from north of the city. I was hanging out at Astor Place a lot and, when I was 15, I was going to places like CBGB’s and really loved that whole music scene. It all pointed to me realizing this is what I want to do. I want to be a New York actor. I want to do Shakespeare. I’m very lucky to be able to say that it worked out.

How did you get your foot in the door after finishing school?

It was a soap! I was on a soap with Parker Posey, and she was just wonderful to work with. It was As the World Turns, and I got two plays at the Manhattan Theatre Club. Then, my girlfriend at the time was roommates with Ted Hope’s sister, Abbey Hope, and she suggested me when the actor playing the part that I was going to do in The Wedding Banquet had a family situation and wasn’t able to do it. They said, “Get him out to Queens. There’s a hotel and they’re shooting a wedding scene today. Get him out there!” So I went out and sat in this lobby, and Ang Lee eventually came by and we talked for a little bit. Then he went away and I was kind of sitting there. I was like, “Should I leave?” [Laughs] So he comes back and says, “You’re in the film. Go, go, go. Go to wardrobe. Let’s get you in the scene.” It was really fun, and I was very lucky.

Is it ever possible to predict how a project might turn out while you’re shooting it?

I know less and less now. Sometimes you do something that’s an incredible pleasure to do, but you don’t know how it’s going to turn out. You can feel a certain level of what people are bringing to it, but that doesn’t mean people are going to be able to see the film. There’s a lot of stuff that I’ve done where I thought it was going to really hit, and for whatever reason, it just doesn’t. There’s a lot of work there that I’m really proud of and wish more people had seen. That said, kind of contradicting what I said, on Spotlight, you could really feel that there was something bigger at play. Every single person was serving a greater purpose. It wasn’t precious, but there was a relaxed comfort knowing that we were serving something much bigger than anyone’s ego. So you could kind of feel that, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to translate. When I worked with Wes Anderson, you could definitely feel a high level of creative mojo going on. You could feel the level of talent and inspiration on set that lifted everyone up. It was the same with Spotlight.

When something like Spotlight comes along, what’s going on inside your head? Dealing with sensitive material and potentially taking on a living person, is it a mixed bag of emotions?

My first reaction was, “Yes.” I felt so lucky to be a part of that. I grew up catholic, went to catholic school, and so I thought, “Damn. Alright. This is finally getting told.” And getting told on a level where it was going to be seen because I already knew who was in the film. It was a real sense of elation to be honest with you. The fact that I had to do this big first scene to Michael Keaton, Mark Ruffalo, Rachel McAdams and Brian d’Arcy James only served to heighten the adrenaline. When Phil Saviano was called in by “spotlight,” after being reported on by The Globe back in ’92 as a victim of clergy abuse, and having gone back in the late ’90s with all this evidence he had culled that pointed toward corroboration in the higher ups of the church with moving bad priests around, and then having that rejected by The Globe—not “spotlight—he felt like he was suddenly being brought before a Star Chamber. He was filled with adrenaline that day because this was the big leagues calling him in. I knew that energy would serve me in that scene.

It was either Mark Ruffalo or Michael Keaton’s character who was surprised in your revealing that one of the members of SNAP [Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests] is a woman. Why do you think there is such a focus on the abuse of boys in the church?

That’s a great question, Kee. Very late in the process of working on this scene, Phil Saviano had a bunch of points he really wanted to include and asked if I could request to get them in. I said, “Phil, I don’t know if they’re going to want to do that.” Tom McCarthy and Josh Singer were unbelievably generous in their collaboration. The script was so tight that the fact they would collaborate with me and Phil just boggled my mind, not to mention their confidence and talent. So Phil made it very clear: “I think we have to also talk about the female victims. It’s not about gay priests, that’s kind of a misconception.” I can’t unravel that question, though. I really can’t. In SNAP, the organization that Phil ran the New England chapter of, and Barbara Blaine founded in Chicago and still runs with David Clossey, I think there might be more female members than male.

I can’t recall where I read this, but wasn’t Phil quite adamant about using the word “groomed” to describe the manner in which he was preyed upon, like so many others?

“Adamant” is the wrong word, but absolutely. This idea of grooming that happens was key to get across, and key to get across in the film because it’s not just some creepy guy who looks like a perpetrator. It’s somebody who very gradually creates this false sense of bonding. It’s so insidious because it comes in the guise of advocacy and friendship. The bond that’s forged between the abuser and the child is part of an insurance policy that will, in the priest’s mind, keep the child from talking about it. The bond isn’t just about, “I’ll be able to abuse this kid.” It’s a way to create this intimacy so the child won’t disclose anything. For instance, when Father Holley—Phil’s abuser—was suddenly brought in as the new Monsignor of this parish where Phil was going to school, he made his first play. When a priest enters the room, the nuns have all the boys and girls stand up. “Keep teaching, Sister. Keep teaching,” he would say, standing behind her and making faces, trying to get the kids to laugh. It’s like saying, “I’m on your level. We have a thing. We can laugh at her together.” That immediately establishes a bond. Then it progressed, progressed, and progressed to the point where Phil felt trapped and couldn’t turn to anybody.

This is quite personal, but did you experience anything remotely close to this growing up?

When I was at Fordham Prep, we had mentors. They were adult figures, people who aren’t your parents that you could kind of tell anything to. You didn’t have the hang-ups or the baggage. In a way, at least for me, I was very lucky. I was very lucky that there wasn’t anyone doing this kind of thing in my midst. This mentor thing was incredible. Having an adult as a ninth grader to kind of take the guard down and talk to openly about whatever you’re going through was a really powerful thing to have in your life as a young kid. But then for other people, to leverage that towards abuse, it’s so evil and heartbreaking. I’m just saying, in that similar model, it was something that was really helpful to me. I just feel very lucky that I didn’t end up in the crosshairs of anyone bad.

How did your conversations with Phil Saviano shape your portrayal of him? What do you take away and what do you sort of set aside?

That meeting when Phil went into The Globe lasted for four and a half hours. It was an epic meeting, so there’s a whole lot more that happened than what you see in our four-minute scene. Phil and I talked about the main points we wanted to make sure to include that might not have been in the original version. Tom and Josh would say yes to this and no to that. They were, like I said, very collaborative. Phil being the survivor of abuse and being where he’s at in life today, I wanted to convey that you can be shattered by something but remain tremendously strong. He’s one of the strongest people I’ve ever met, if not the strongest. I wanted to convey what he was able to endure, what he was able to come through, and what he was able to accomplish on his own as a one-man investigative journalist, when he wasn’t a journalist. And yet, who knows what would’ve happened if “spotlight” hadn’t called him in? If “spotlight” didn’t enter the picture, maybe none of this would be happening now. We don’t know. It was important for me to convey Phil’s strength of character.

What was Phil’s reaction to seeing the film, not to mention all the other survivors?

That was truly incredible. You should check out his Facebook page because a lot of survivors have been checking in with him and talking about the film. It’s so wonderful to see the praise this film is getting. You read the reactions from some of the surviving folks who have seen the film and it’s so humbling and so moving. And Phil’s been forwarding me stuff. I’ve gotten to know a lot of his pals through SNAP. For someone who does what I do for a living, there’s no greater reward than hearing from individual after individual that they feel validated because we told this story.

How’s Phil doing these days, health-wise?

He’s great! You know, he was HIV-positive in ’84. He was HIV-positive before it was even a death sentence. He had a doctor at—I think it was at Brigham and Women’s or something like that—one of those great hospitals up there in Massachusetts. It’s like, “I have a gay male patient who’s this age. Let me run this test.” They told him he had this virus, and it was so early that Phil was just like, “Okay. What does this mean?” Very shortly thereafter, it was considered a death sentence. He had full-blown AIDS in ’92. He’s since had a kidney transplant, but none of his family members matched. A woman from SNAP, another survivor of abuse from St. Paul, Minnesota, donated her kidney. He’s just doing great now. Honestly, it’s really inspiring being around Phil because he’s just absolutely doing great and he’s become a really close friend. It does the heart good, you know?

Looking back on everything that you’ve done, can you share a memory or something someone said that made a big impression on you? Maybe an unexpected lesson?

I was at Film Forum last spring to see three of my favorite films, Satyajit Ray’s The Apu Trilogy. I had never watched them on the big screen, in one sitting, before. Ray has such an open heart toward all of his characters and he depicts life and our flaws engaging in it, like no one else. I don’t want to give away the end of the third film for anyone who still has yet to see them, but it is just overwhelmingly beautiful. And right after it ended, the thought came to me, “Be a servant. To those around you. To what you do. Be a servant.” It’s hard to do. But I think that’s how we and our lives expand. And to be honest, that’s what I consider to be the greatest strength of Spotlight. Everyone who worked on the film was serving something huge. The story of how the widespread abuse of children was covered up for so long.

Just changing gears here, you have M. Night Shyamalan’s Split coming up, which is of course shrouded in secrecy. Can you reveal anything without getting into trouble?

Do you want me to email you the script? [Pause] I’m just kidding…

I was like, wait a minute. “I could make a fortune.”

[Laughs] I signed a NDA [non-disclosure agreement], but if you want the script, just don’t tell anyone. Just delete it as soon as you download it. Umm, I can’t tell you anything because I really don’t know anything. I have a very specific part early in the film. But I honestly don’t know and I didn’t want to know any more. I just wanted to be fully free with the thing I was doing in my scene. I didn’t want to get too much information about what happens in the rest of the film. I’m actually a big advocate of enforced ignorance when it comes to working on things. Sometimes when you know too much, it can interfere. So really, your guess is as good as mine. I know it’s definitely a M. Night Shyamalan film and things get very M. Night Shyamalan. [Laughs] There are some intense and thrilling things that happen, for sure. He was lovely. I really enjoyed him.

I watched Unbreakable the other day because it happened to be on TV, and it’s actually really good. I think people fixate too much on The Sixth Sense. He never stopped being interesting.

Strangely enough, filming Split down in the Philadelphia area, it felt like he’s had a shift in how he approaches production. It’s similar to what Wes Anderson did after The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou. It used to be a big fat production with trailers and everything, and then Wes went with this new model of keeping all the actors in the same hotel, house or just close by. When you’re on his set, you get dressed and made-up in the hotel lobby. The day becomes far more about the creation of the thing. At the end of the day, you have candlelight dinners with everybody. It’s really incredible. I think Moonrise Kingdom cost $16 million dollars or something. You’d never think it would be possible to achieve what he did on such a staggeringly low budget. And everyone’s working for scale. Maybe before The Visit but definitely after, I think M. Night changed his approach to production, too. From what I saw on Split, it felt like that Wes transition where he’s taken steps to carve out any unnecessary fat off the production process. Now there’s real freedom for him on set to explore and work his vision. There’s an interesting correlation there.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments