The thing that I find tough is when a filmmaker is expected to disclose their specific trauma in order for society to feel like their story is valuable. I think that’s really dangerous.

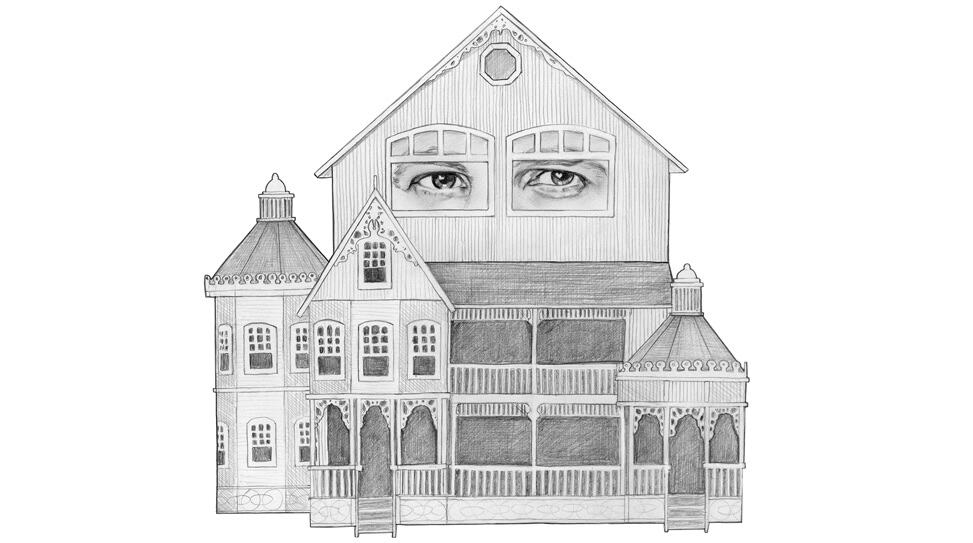

Illustration by Jenny Mörtsell

Art Direction by Kee Chang

A young man walks into a coffee shop and shoots the place up before turning the gun on himself. Based on Brian DeLeeuw’s 2010 novel, In This Way I Was Saved, Adam Egypt Mortimer opens his highly imaginative sophomore feature, Daniel Isn’t Real, in this way. The horrific crime is witnessed by an 8-year-old boy named Luke (Griffin Robert Faulkner) who’s processing the bloody aftermath when a slightly older boy appears beside him. At first, this Daniel (Nathan Reid), Luke’s new confidante, steers him away from upsetting realities, beckoning him into a play world of sword fighting. He’s such a positive development in Luke’s unstable home life that his mother (Mary Stuart Masterson) is charmed to discover Daniel is imaginary. That is, until a prank sees Daniel wheedling him into almost killing her, with Luke grinding up her meds into a smoothie drink. She demands Luke banish Daniel into grandma’s antique dollhouse, a symbolic gesture she hopes will curtail her son’s overactive imagination, which would effectively sever their friendship.

A decade later, we rejoin Luke (now played by Miles Robbins), a college freshman who visits home to witness his mother’s continued descent into paranoid schizophrenia. Fearing that mental illness runs in the family, he seeks counsel from a doctor (Chukwudi Iwuji) who suggests it might be time to conjure Daniel back into his world—a therapeutic way perhaps for troubled Luke to confront aspects of his lingering childhood trauma head-on. So Luke unlocks that dollhouse, where it seems Daniel has been in some purgatorial other dimension all this time waiting to be unleashed.

Once again, Daniel (now played by Patrick Schwarzenegger) is at first an enormous boon for Luke, quelling his anxiety, in helping him score better grades, and become more sociable. Luke makes friends, notably an aspiring artist named Cassie (Sasha Lane). But while Daniel’s carnal appetites may just be an exaggeration of Luke’s own, this entity appears to have a nefarious side wholly divorced from its host. As its influence grows, Luke begins to fear that Daniel may be no psychological bogeyman but an ancient force—one that perhaps drove the shooter he saw at age 8 to the mass shooting. A bulk of the film is centered around Daniel’s aggressive attempts to uproot Luke’s life and our protagonist’s increasing inability to control Daniel or maintain a front of normality to others.

Daniel Isn’t Real is a haunting—and supremely entertaining—excavation of the hollow shapes that young men can contort themselves into when lacking emotional support, feeling that the hopes and the hunger in their lives have been frustrated. Meanwhile, Mortimer’s extravagant, gnarly vision will surely send genre fans’ teleporting into a previously unseen realm of phantasmagoric horror.

Daniel Isn’t Real hits select theaters, on Digital, and On Demand on December 6.

Congratulations on the incredible reception you’ve been receiving on the festival circuit.

Thank you so much. It’s been amazing. This year has definitely been a high point of my life. I’ve been trying to go to festivals with the movie as much as possible and meet people who are seeing it. It’s been so satisfying and delightful to have this reception. It’s been awesome.

I actually have video of you accepting the Best Director prize at the Bucheon International Fantastic Film Festival on my phone. That was a moment.

Oh wow! You were there? That’s so cool! I gotta say, getting an award in Korea where they currently have the best film culture on the planet was—I just couldn’t believe it. It was so amazing.

Daniel Isn’t Real is an ambitious movie and also a complete movie. The vision and the craftsmanship is totally there from beginning to end. I was really impressed that you were able to pull this off. This was seven-plus years in the making, from your decision to go forward with it and the film premiering at SXSW, is that right?

Yeah, I think it was in 2011 that I read the novel, and asking Brian [DeLeeuw] if I could adapt it and deciding to work on it together. But that journey wasn’t like every single day for seven straight years that we were working on it, although we were working on it on and off for significant periods of time throughout that length of time. Then I started working on it with SpectreVision in 2015. Once they say, “Okay, let’s make the movie,” you immediately feel like you don’t have enough time. But there was enough time for me to dial in exactly how I wanted to do it and figure out how to structure the movie from a stylistic point of view—not only what it would look like, but why it’s going to look like that. Out of the entire process, that’s the most satisfying aspect: It’s when you have the script and you’re thinking very carefully about how to film it, and not yet on a day where they tell you, “We have 15 minutes left! You have to go!” It’s about thinking concretely about how to make the movie, which is my favorite part of the process.

I understand that you made a 40-page document to outline the visual style you were going for. I love what you’ve been calling the visual style of Daniel Isn’t Real: kinetic maximalism.

Yeah! We had to accomplish this thing of taking something that starts out isolating and depressing and lonely and scary, and getting it to a place of kinetic maximalism, a place of depicting the feeling of a manic episode. We also had to get the movie to go from an almost intimate family drama or a psychological thriller all the way to cosmic horror at the end. What concerned me was, how do you go moment by moment so you’re starting in one place and end up somewhere totally different where it still feels like the same movie? The style guide was this really comprehensive way for me to communicate that with people and divide the film up into certain sections and sequences, saying, “This is the manic section” or “This is the paranoid thriller section.” What do the rules look like? What are the rules for filming an imaginary character in a way that the audience would believe that certain people are seeing him and other people aren’t? So that document was really helpful. Everybody read it and responded to it. But even if nobody had read it, I think just the forming of it made it possible for me to understand how to do the movie.

Let’s talk about what’s happening to Luke in this story because you wonder, is he mentally unwell? Is Daniel truly imaginary? Is Daniel the manifestation of Luke’s id? To me, what feels most tangible beyond suggestion or interpretation is that Daniel is an ancient evil. We see Daniel truly angry for the first time when Luke is mockingly reciting Exodus 20 from the Bible. That seems to situate Daniel’s origin to a fairly concrete place in my mind. Maybe it’s a combination of these things.

I guess there’s certain things I wouldn’t want to give away from the movie, but it’s a story about a kid who is struggling to be good, right? It’s about finding a way to externalize the battle we have between “I want to be a good person who’s empathetic” and “But I have these terrible impulses and I have a voice in my head telling me to do something different.” If you boil it down, I think that’s something hopefully anybody can relate to. The most “normal” person on the planet will be able to relate at least a little bit to that idea. So that was the most general thing—everyone has demons—and you externalize it into this other character, this other creature. I also do sort of have a cosmology in feeling that there’s a way I can believe human evil is almost a cosmic element. It’s like believing in the devil but believing in the devil not as something that’s necessarily a person or a character. The devil is a cosmic fact of being human. That’s why in this film we not only see Daniel but, like you say, we suggest an ancient lineage of demonic forces. We see black holes and the void and the abyss and these very big visualizations. That’s because I think we feel as people like, “Woah! I’m one tiny person in the world, but I have all these big scary thoughts!” I wanted to connect that out to the cosmos. I derived some of the ideas in the movie from Tibetan Buddhism, which was a tradition that I had studied a lot when I was the age of the characters for the most part. It’s about looking at the world as a great cosmic wheel that’s spinning. And how do you get off that wheel? How are you responsible for the way that wheel is spinning? Really, I’m thinking about these cosmic forces that we can relate to and connect them to this tiny feeling of being a person like, “Am I struggling today not to be an asshole or not?” That question can become a huge, terrifying cosmic force.

I only noticed in my second viewing of the movie that you tweaked the famous [Hieronymus] Bosch painting.

Yes! I know! We had our art department take the Daniel character and put him into one of the Bosch triptychs. I love Bosch and how Bosch depicts a really terrifying, chaotic world that he seems to feel we live in. That’s fascinating. This is a movie that starts with a college student in modern-day Brooklyn, and then to connect him to the feelings of Hieronymus Bosch was so much fun. It’s like, “Ohhhhh shit. This is a thing! Hieronymus Bosch must’ve been familiar with these feelings as well. He saw what Luke is seeing.”

You’re extremely proficient in balancing opposing forces. I love the idea and your execution of Luke locking Daniel up in his grandma’s dollhouse, for instance, in the same way that I enjoyed the whole set-up where Luke is on Daniel’s turf in a pseudo The Nightmare on Elm Street: Dream Warriors realm in the film’s final moments. The whimsy goes very far in your nightmares. You scale the heights of Pan’s Labyrinth in that regard.

We see it from the very beginning, right? A little kid locks his imaginary friend away in a dollhouse and when we return to it at some point at the end of this story when they’re adults, we’re gonna finally explore this world. Now we’re gonna explore it from an adult point of view. I think what might be scary to children can also feel sort of dark fantasy and maybe that’s, as you say, whimsical. When you reapproach it as an adult, what if this dollhouse really is a gateway to cosmic-sized neuroses and violence and pain? What would that look like? That’s a really interesting thing, and a cinematic challenge. You want to make it so big, you know? First it’s a tiny dollhouse and now it’s big enough to fill a widescreen image. So how do we get there? I guess we got there, somehow. [laughs] We dragged ourselves into that cosmic world.

You certainly brought the goods to the finish line.

Who knew that New York City has these fortress structures that really lend themselves—once you light them and smoke them up and put cool things in them—to feeling like otherworldly, ancient places? They’re just right there in Staten Island.

You’ve previously spoken about this idea that horror movies calm the disturbed and disturb the comfortable. Let’s get into that a little bit.

I really believe in that. That quote originally comes from Antonin Artaud, the French philosopher and actor and theater artist behind The Theatre of Cruelty. I find a lot of resonance in that philosophy when I think about the horror movies I like. I’m much more prone to enjoy horror movies that are upsetting than ones that are campy. My taste tends to veer towards either the really dramatic horror films like The Exorcist and Jacob’s Ladder or to French horror movies like Martyrs and Inside, which have this understanding that horror can be so deep and expose our real fears and have a real sense of emotional violence.

Empathy is of huge interest to you in the film, and I can imagine in life. Maybe it’s unpopular to empathize with Daniel because he does deplorable things, but there’s a tragedy to him that feels deep and human. I’m thinking of that scene in particular where he’s walking on the water. Luke asks him how the water feels and he replies, “I don’t know.” Envy is such a human and revealing trait.

I love that you’re pointing that out. I think that’s really true. Daniel has a tragic flaw. He could be such a positive force and really does help Luke at first. He really does have these incredible powers of perception and motivation and inspiration and creativity. But he’s so stressed out. He has this rage and this desire to be the one who’s in control, this desire to have physicality to touch other people, and this desire to express sexuality and violence. That just drives him insane. So instead of being able to enjoy his collaboration with Luke or find a way to be a positive force, he just fucks it up every time. The minute he gets an opportunity to have a body or the minute Luke lets him experience the world, it’s just a disaster. I think you’re totally right in seeing that as a tragic flaw, and where does that come from for him? It’s basically like he’s impatient. He can’t stand it. He’s overwhelmed by what it means to have a body. He can’t handle it. That’s certainly a tragic flaw. I don’t know that one hug would help him, but we can try to hug Daniel to see if it helps him.

You had an imaginary friend growing up. When does an imaginary friend disappear?

God, that’s such a great question. I remember having Mr. Nobody. I have very specific visual memory of introducing my father to Mr. Nobody. I was eating lunch with Mr. Nobody at the time. He was this faceless, egg-shaped character with arms and legs, maybe like a more perfect Mr. Potato Head. I remember believing in him. I remember my dad playing along. But I don’t remember not having Mr. Nobody. It’s the sort of thing where you wake up one day and you’re less of a child and the world is less imaginary. I think what I did carry for much longer was anthropomorphizing objects. I was surrounded by stuffed animals that I loved when I was a kid and I would talk to them, up until—I brought some of them with me to college. I had less of a sense that they were alive, but it took long for me to let go of the idea that inanimate objects have feelings or have a life. I think a lot of us still have that a little bit, which explains why our homes are so cluttered. But yeah, I don’t remember a day that Mr. Nobody blanked out. Luke shuts Daniel away, but you get the sense that he always maintains some sense of his own reality, which is why it’s possible for Daniel to come back up later. We carry that spark with us forever.

Trauma and self-destruction are also huge themes that you play around with. I don’t mean to beat around the bush with this: How important is it that filmmakers experienced trauma in their own lives to understand, even remotely, what’s happening to their characters? I mean, would you want to know what a manic episode feels like?

I tend to draw from personal experience because I think that’s the only way to make the movie good. The personal experience that I was drawing from had to do with a best friend who went through something very similar—a very intense, manic episode and schizophrenic break when we were the age of these characters. It’s my memory of what that felt like to be involved with, to be surprised by, and not understanding what was happening. It’s my memory of trying to deal with it and the traumatic fallout. Early on when I was reading the book and thinking about the movie, I realized that was something I could bring to this because it’s something I experienced, which had really traumatized and bothered me when I was young. I had been carrying that with me for so long. Then being able to reach back into those memories to try and communicate that feeling honestly in the movie became a really important part of my goal. That’s where the idea for the style of the movie comes from. It’s one thing to tell the story in terms of what happens, but the more important thing to me is to capture the feeling of it. How does it happen? As for going through trauma, is that the responsibility filmmakers have? I don’t know. That’s a tough one. The thing that I find tough is when a filmmaker is expected to disclose their specific trauma in order for society to feel like their story is valuable. I think that’s really dangerous. Maybe the work itself can be the disclosure of the trauma, you know? I feel relatively comfortable talking about my own life and certain traumatic incidents—I often talk about what it was like when my mother died and how that changed my perception about the universe and about death and things like that—but I don’t know that we should force people to share that kind of information. [laughs] Some poor filmmaker is standing there in a room of 400 people being asked, “What is your trauma?” That’s a little bit scary. The thing that makes me sad is when I think there are people who interpret what I do as exploiting those feelings, but that’s really uncommon. The thing that I’ve found I’ve gotten so much satisfaction from is, every time I’ve screened this movie, someone will come up to me and say, “I experienced something very similar to this and I’ve never seen it depicted so truthfully. I really love that about this film.” That’s one hundred percent my audience, and the people who aren’t connecting with it just don’t get it and that’s okay.

In my opinion, you’re asked way too much about your inspirations and references. They run the gamut from Face/Off to Requiem of a Dream, from Persona to Videodrome. I think it’s more important to bring to the fore just how much of an original vision you have. Daniel Isn’t Real feels entirely fresh and reinvigorating. It’s so rare. That alone should be celebrated.

I really appreciate you saying that, that despite the references or the inspirations it becomes its own thing. I’m so attracted to what movies can do when you think about their aesthetics, like what a movie means based on how it feels instead of just what happens in it.

It’s experiential.

Yeah! Immersive and experiential, you know? I think if you read the Wikipedia entry of a movie, that’s not the movie. The movie is how it feels. What is the texture and the color? What are the sounds of people’s voices and the music? How does all of that make you feel? That’s what the movie is. That’s how I’m trying to approach my next movie as well.

I read on Gizmodo that your next film will be Archenemy, produced again by Elijah Wood’s SpectreVision and starring Joe Manganiello in the lead as a superhero. What can you add to that conversation?

Add to the superhero conversation?

Yeah.

It’s exactly the thing that you’re pointing out about this movie. The thing that I love the most is how to tell the story. How does it feel, what does it look like, and how can we make that truthful and different? One thing that I’ve found lacking in superhero movies as somebody who grew up loving comic books is that I haven’t always engaged with the aesthetics of these kinds of movies. I’m trying to do something that’s my aesthetic—a visual style that is unique to me and the things that I think are beautiful—with these kinds of characters and what that would be like. I want to similarly tell a story that’s both a disturbing, intimate psychological drama and something really cosmic. I want to tell a story that is lyrical and sad and romantic and brutalist. I don’t know how closely I’m going to achieve this, but I keep telling people I want to make a superhero movie that feels like Wong Kar-wai made a superhero movie. I’m talking about early Wong Kar-wai back when he didn’t have very much money, like I don’t.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments