If you can house imagery for the ages that’s going to have an indent on a generation, your job is done.

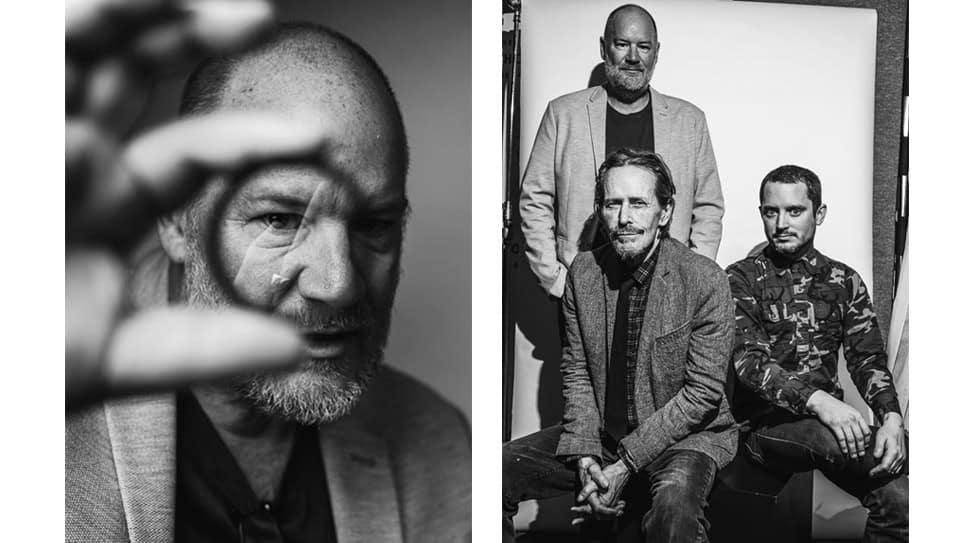

The Greasy Strangler producer Ant Timpson is back on the film festival circuit, this time with his long-awaited directorial debut Come to Daddy. The wonderfully deranged and darkly comedic movie is bound to become this year’s sleeper hit. It’s also a cult classic in the making.

The New Zealander recently opened up to Talkhouse about the deeply personal genesis behind his new project involving his father’s passing: “I became overwhelmed and adrenalized with a feeling of wanting to create something to bond us together. Something about fathers and sons. Something permanent. To make a film inspired by those films we watched together when I was growing up. A thriller. He loved thrillers. And it should have moments of dark comedy. Dad always laughed at my pitch-black sense of humor. Nothing shoves you in the back harder than watching a parent cark it in front of you. When mum died, it was a gut shove backwards into a cocoon. This time, with my father’s passing, it propelled me forward,” writes Timpson. Now we know what was at stake.

On a weirdo wavelength from the get-go, Come to Daddy kicks off with two wildly different quotes about fathers. First, an epigraph from Shakespeare of a high-brow variety. The other by Beyoncé: “There is no one else like my daddy.” Elijah Wood stars as Norval, a mustachioed hipster who obscures his insecurities with high fashion and fancy lies. Consider his faded monk’s haircut, the wide-brim pork pie hat, hammer pants outfitted by a flowing tunic, and the rose-gold limited edition iPhone designed by Lorde. He is a self-anointed purveyor of “blazing beat” (that’s DJ) and a 35-year-old man-child living at home with his mom in Beverly Hills. Norval’s life is about to take a sharp turn when he unexpectedly receives a letter from his estranged father who walked out on him when he was 5, requesting his presence at dad’s oceanfront home. Brian (Stephen McHattie) seems to want to reconnect, but it turns out this guy is shady as all hell: an inebriated, haggard geezer whose devious smirks Norval grows increasingly suspicious of. To reveal more would do the film a disservice, but suffice to say, what begins as a cringeworthy reunion pivots into something totally bonkers, and finally heartfelt. This is Timpson’s wicked universe after all.

Come to Daddy opens in select theaters on February 7.

You participated in a post-screening Q&A last night. That must be refreshing for you since a huge chunk of Come to Daddy is spoiler territory. You can talk about everything out in the open with festival audiences in ways you probably don’t want to with the press.

That’s the thing I keep thinking about. I’ve been hounding the whole no spoiler thing from day one, but with those Q&As I sort of overshare information without realizing that might be going out in a Tweet. [laughs] But I think people really love that aspect of it. It’s cool to pass this secretive movie on to people without tearing the wrapper too much. You just wanna give as much as you feel like they should know without actually revealing too much. It’s a mystery box so if you know most of the thing inside of it, it sort of lessens its impact. That’s always the biggest concern in creating a script like this. If you give too much advance information, it’s going to have a watered down effect and dilute the overall idea of what the experience should be. It’s always supposed to be this crazy ride at an amusement park where the wheels feel like they’re just about to derail off the ride.

I love your worldbuilding. The pop culture references bind the film to our reality, but the physical space feels askew and distinctly yours. The film has so much personality.

Well, the location was like number one for me. I felt like we needed to find a singular house that had a really unique personality to it. I always wanted the house to be a character, as strong as our leads are in a way because it adds so much heft to the dynamics of the narrative. It took a while, but when I saw that house I was just like, “This is crazy,” with this weird UFO sticking out of it. It was right by the sea too. The other houses we looked at were off cliffs looking down and I was like, “No, you gotta be right into the environment.” Because the film changed a little bit, there was a lot more of the haunted house aspect to it and we needed to have a house that we can explore a bit more with layers and things. We do cheat a lot in the film in terms of what the house actually has. But yeah, it was a major part of the film and it was about locking down that main location. Once we had that location, I was actually there six months early. I could go in there and just feel it out. I would send the writer [Toby Harvard] drawings of the actual schematics of the place and send a Google map to show where it was. Then I said, “This is how we’re gonna have to adapt the script.” It was about fine-tuning towards that exact house. It’s quite weird because you don’t usually get the opportunity to have that much time to write the script to fit. That’s why there’s dialogue in the film about the house being like a UFO. When I first saw that house, I thought it looked the USS Enterprise from certain angles. We were incredibly fortunate to have that location locked down early on. It’s such a big part of the film.

I read your thoughtful write-up for Talkhouse before watching the film and it imbued Come to Daddy with a lot of dimension. What really struck me is how you had made these “home-made horrors” as you call it as a kid and your eventual return to the director’s seat decades later with this film. Your father’s passing obviously played a huge role in the shaping of this particular film, but I wonder if you’d been thinking about directing in all the years you were supporting other filmmakers’ voices in a producing capacity.

That’s a good question actually. Was I like aching behind-the-scenes as I did their work? [laughs] No, I think that would’ve made me one of those terrible creative producers where they just wanna keep putting their own ideas in them. Although I kinda am because I’m a very early-on producer. I come on from day one and have a big part in it. With The ABCs [of Death] series, it was kinda like now I’m creating a concept for the thing. I felt like I was getting enough directorial nuance on some projects, which was probably keeping that part of me subdued enough. Then after the death of my dad, it was game over. I knew things are gonna have to change. I think “get tryin’, don’t get dyin’” is what my chief coin phrase was for it. [laughs] So that was when everything cracked. The facade cracked away like, “You’ve been supporting other people’s dreams. Time is running out. You gotta go back to being a kid that was manic for film. You were more of a movie maniac then, more than all of these people you’ve worked with, when you were 12,” or 13 or however old I was with the early cameras. That’s the kid that’s just been subdued and crushed and now he’s coming out like a maniac. It was an awakening and it was profound. The scary thing was, this is not an easy thing to make in this moment in time. The worst thing was convincing myself it was going to happen because up until the day we shot I kept thinking, “This is just the usual talk. It won’t happen.” It wasn’t until I literally got on set that I realized it was actually gonna be a film.

You go into a self-protective cocoon because you can’t be good at what you need to be good at if you’re completely, constantly thinking about moments of being the director on those other films. It did just get pushed deep, deep down. But after my father went away, the desire came up and started bubbling away. On other people’s films, you just have to be there as a supportive producer—an annoying creative producer—that wants to get ideas in and everything else. But no, it would’ve been terrible if it was bubbling up right up here. It’s been sort of dormant for a long time.

Were films your central bonding activity with your dad? What do you most remember?

Boxing. We used to watch boxing together apart from movies. He was a really physical guy—an athlete. He played a lot of sports and he was very capable at a lot of sports so I grew up looking at him playing cricket, and doing boxing and rugby. In terms of movies, I guess I absorbed his sense of film. He loved British character actors: tough guys like Richard Harris, Oliver Reed, Peter O’Toole and Richard Burton. Real hell-raiser ‘60s actors. Boozers off-screen, boozers on screen. The wild men of that sort of era. We watched a ton of films together. I’m actually writing an article about those films now that inspired me and the vivid memories of seeing them with him. I was watching them thinking, “This is way too adult.” [laughs] I was a 9-year-old watching Sean Connery in that Sidney Lumet film [The Offence] or whatever. I was talking last night in one of our long drunken sessions about the films that inspire you: “What was your style?” All these young filmmakers are like, “Mine was Spider-Man.” I was like, “Whaaaaaat?” Mine are like The Taking of Pelham 1, 2, and 3–gritty thrillers that really formed and shaped my love of film in a way. Then I saw all these other kids films that you get dragged along to, but even then, they were kind of weird, mean-spirited ones like The Light at the Edge of the World. That was supposed to be like a Jules Verne thing, the Doug McClure stuff with the crazy rubber monsters. It was like a Viking odyssey with people getting skin peeled off their bodies. My parents totally didn’t get that right, showing me the most obscene PG movie of all time. So it was a really weird, diverse line-up of cinema and I connected to it I guess. Also, I was unusual in the way that I used to go to cinemas when I was 7 by myself just walking up the road. We had a local cinema called the Crystal Palace and I would spend the day there watching spaghetti westerns, Italian gangster pics and way-too-young-to-be-going-to R-rated films. I didn’t even care if I was going with friends. Going with friends was cool, but I didn’t care if they were coming or not. Going to the movies was more important.

You moved from New Zealand to Beverly Hills in 1977. I guess you were around 11? Speaking of that experience, you’ve said it “both normalized showbiz and amplified it.”

Yeah, it was like looking behind the curtain. It was the first time that I met children of real movie stars and that was kind of surreal. I met The Fonz, Henry Winkler, at the peak of Happy Days mania. It was crazy. Another big show on TV at the time was Get Smart and Don Adams’ daughter, Tracy Adams, was a friend in my class. I went to their house, this huge mansion, and I was like, “Oh my god, this is how that side lives.” There are other moments that I remember: I went to a party of one of the kids at school and he had a full backing band of studio session musicians playing “Brown Sugar” from the Stones incredibly well. I was just thinking, “I’m from New Zealand. This is not normal behavior at all.” [laughs] It was a really surreal introduction to entertainment: this thing that used to be in a box for me back home in dinky old New Zealand and realizing these are the people creating entertainment, and bridging the two and loving that aspect. It’s no spoiler to know that I saw Martin Landau—I’d seen him on Space: 1999–drunk, walking around Safeway in the morning with Doritos chips or whatever. It was like, “This is the world. They do this.” So for me, it was a real instance of maturity in terms of understanding the business and falling in love with both aspects. I’ve always loved the business. I love the Hollywood mystery stories. I love how films are put together and how they’re deconstructed. How they’re financed. The disasters that happen. The successes that happen. Just as much as watching films, I love reading a great how-to book as well. That was all formed at an early age. That was also the first year the Z Channel started in L.A., a box that you had in your house. I remember many nights sneaking down and clicking on this box. I was 10, turning 11 during that time. I was exposed to a lot of classic adult films through this cable box that we’d just bought. It was like the early HBO in Los Angeles. I remember seeing Slap Shot, Annie Hall, The Exorcist, Taxi Driver—seminal films they had on that channel. That really fueled my interest as well.

Did being there at the epicenter of the film industry suddenly make “the dream” look attainable to you, even at such a young age?

I’d be lying if I said I was like, “I want to make movies!” like that kid having the moment in those documentaries. [laughs] I never felt that connection at all. It was only when I really got access to a video camera a little bit later on around, geez, 17 or something. So I wasn’t that earlier Super-8 kid. I used to write stories. I wrote Stephen King-style short stories and gave them to people to read. I wrote a fantasy novel when I was 16 or something. That was my creative output. It wasn’t going out and shooting stuff at that age. But in terms of processing and understanding and building your own narratives, that was happening earlier on. I was terrible at lots of elements of school, but my writing and creative writing in English was always super strong. It seems obvious that I was going to veer in that direction somehow. Then I left university purely to work on film, but I had no idea how to do it. I just knew that I didn’t want to be a lawyer, that’s for sure.

I do know that you briefly studied at the University of Otago. So you were on the road to becoming a lawyer?

I wasn’t on the road. I was literally starting out. I was halfway to go down that path, but I had a terrible first year at Otago. It was like Animal House 24/7 so it’s got a high failure rate for first-year students. We started a house that was outside of the university district. It was first an asylum and a hospital that was converted into a university hostel. There were no rules in place and they didn’t understand how they were gonna control the kids. It was like everyone who couldn’t get into a decent hostel was put into this hideous hostel. It was incredibly strange, violent, alcoholic and we were doomed from day one. The smart people got the hell out of there early on and went back into town. The rest of us just turned into Delta House from Animal House for the rest of the year. Carnage. It sounds nice doing intermediate law, but the reality was that I had no interest in it. I was doing it because I wanted to impress my parents, or to be the honorable student that had spent a lot of time in school to get a scholarship and then go do what I thought they wanted me to do. But they were so supportive at the end of the day like, “Well, what do you want to do then? That’s what we thought you wanted to do.” Then I started making film festivals during university and charged people money. I’d go rent VHS tapes and project them. That was my very first idea that, you could make films, but you could also show films and make money. That’s why I think I’ve managed to be involved in every facet of the industry from young days through and get an understanding of it from there to production to the distribution to how it all works. I think it’s quite valuable for a filmmaker to know the whole machine—not just one part of it.

Was that the Strange Film Festival?

No, no, no. This was way before that. This was a completely illegal, bootleg festival.

If there is one certainty about filmmaking, it must be that everyone approaches the craft differently. I’m curious about your experiences producing both The ABCs of Death and The Field Guide to Evil anthologies, which involved many directorial voices from many different countries. Did you notice any through lines in what they were doing?

For Field Guide, definitely, because it was way more honed and the creative canvas wasn’t so wide open and carte blanche. Field Guide had a more narrow set of criteria for them to work on so it felt more formal and more elegant in terms of what we were trying to achieve. The brief was tight. With ABCs it was like, “Go fucking crazy,” which is why they were tempted to do it. Because it definitely wasn’t the money that we were playing with. [laughs] The first one was kind of anarchic, you know? It’s a fuck you to whatever was out there at that moment and I think that really appealed to people. I wanted to create a zeitgeist moment, capturing the voices of an entire range of genre filmmakers of that moment in time. Secondary was that I didn’t know how it’s gonna turn out. It sounds like it could be a disaster, but it could be cool as well. There’s also the sheer bravado of actually going for it. No one knew what it was gonna be like sitting in a theater experience watching 26 of these things barreling down. I remember the first screening was crazy. I don’t agree with everything, but the flow was nutso, and I think for the right people it really worked. I really like to have a worldwide community that grows up together because of the competition aspect of it where we’re gonna save one spot for filmmakers from around the globe. Through that competition, I’ve actually met just as many filmmakers as I do working on the actual films, and I’ve seen them come up through the ranks and start doing features. It was a very close-knit community in the end and wide-ranging in terms of influence. So yeah, it was a wild experiment. We had no end in sight. It was just like, “Let’s jump on this crazy pony ride as far as we can.”

Turbo Kid came out of The ABCs anthology, right?

Absolutely. That was the entry for T for “turbo.” It got really close to winning the whole thing. At one stage it was gonna win—it was between that and Toilet. I remember writing to those guys. I remember their enthusiasm and their affection and the fact that they had a bit of a following. I had a connection to Fantasia [Film Festival] and to Montreal also, and that helped. I was looking for certain things that might expand and I liked the world vision they built just within that short. They blasted out a script. They had all the ideas and all the characters already. I was like, “This is really good. Let’s get this going.” It was just a beautiful confluence of moments in time really.

And it looks like you’ll be producing Turbo Kid 2.

Yeah, it’s taking a long time. We all got busy with other projects. But it is a new script. We had one draft and we’ve moved on to the latest draft we have now, which expands the Turbo Kid universe in a lot of ways and brings back a lot of fun characters. So we’re just gonna nail that with them. I think it can happen because the amount of loyalty to that first film was really exciting for all the funding bodies. They’d never seen that type of loyalty towards a film they’ve been involved with before. It’s very tribal, you know? It’s the cosplay elements and the tats and just how it’s been developed in terms of merch, which has been really successful. There’s definitely a loyal crowd waiting for more from that universe. It feels like it should happen.

You’d be hard-pressed to find people who love cinema as much as genre filmmakers do. The enthusiasm and their obsessive nature is just on a different level. Film bleeds into every facet of their lives. You owned a dedicated film store called Filmhead at one point. What had been your most prized possession in there?

To be honest, the prized possessions were all back in our homes. In my house, we had some really cool shit. Really, there was nothing in the store that would’ve made me cry tears had it burned in a fire. It was more for the public. We felt like that was kind of useful for filmmaking and for film fans. But yeah, there was no holy grail item that we ever put out. We kept those for ourselves. We had unique items and props and things that were there for us to pass down to kids. I still think collecting is kind of ridiculous as well. I have a real love/hate feeling with the collector mentality and with fanboys going too far obsessing to that level. I appreciate it when I see fans do it with the tats and everything, but I love cinema so much that I would never wanna shove a Puppet Master tattoo on my arm. Then I would be the illustrated man trying to get it all burned onto my skin. My memories are up here and they keep me happy. I don’t need to have the physicality of things. I have 10,000 posters of films and super rare materials for movies like Freaks from early exploitation right through. But they’re in boxes sitting around. They don’t mean anything to me.

Since you bring up this idea of passing things down to your children, I’m curious about your sons. Do they have the same kind of appetite for films that you had at their age?

That’s really cool. That’s a good question, mate. I was talking about this last night as well. With my dad, it was more like I was just another participant in what he was going to watch. It wasn’t like, “I’m going to force this on you.” It was a background study kind of vibe. I have a real detestation for people who force their taste on their kids. I find that foul. I’ve seen people trying to groom their children into miniature versions of themselves and that’s the most disgusting version of what ego is all about. It’s completely controlling and strange to me. For me, I love watching my kids develop their own taste and find things. Sure, I showed them crazy Godzilla movies when they were young, but everyone should watch Godzilla movies when they’re young. [laughs] It’s normal. But then they go explore other stuff. At the moment, they’re loving early Adam Sandler movies. They found those themselves and they love comedy a lot. I went through a phase of loving dumb American comedies as well. So your kids are you. They’re going to end up hating you and being you eventually no matter what you do. I kind of think movies are the one chance for them to develop their own palate. Less interference from you might mean it’ll be more exciting for you too to see what they bring back. They’ll show you things, instead of being little homunculi versions of you that you created. It’s scary and narcissistic to think that you want another you, you know? They’ll turn into you anyway so don’t worry about it. Just let them discover the world themselves and find their own cinematic taste. It might be cool and surprising and really interesting.

How old are your boys now?

They’re 9 and 11. Everyone’s like, “When you have kids, you’re not gonna ever let them watch the crazy, extreme stuff,” and it’s kind of true. They used to hate me at the film festivals when I would play all of the button-pushing, extreme cinema. I think kids have a really natural way of finding that material when they’re really young. But they’ll see one thing that’s too early for them to be watching and that will be a benchmark that defines a lot of that internal censorship range in terms of what they can handle. For one of my boys, for some unknown reason, he must’ve seen Men in Black on TV when he was super young. He has this image of the face breaking—he described it to me and I was sure that it was from Men in Black. I don’t know how he watched it that young, but he was 3 or something. That traumatized him and I didn’t know this until he told me years later. Now he can’t watch anything too scary. Then my other boy is a complete psycho who wants to watch every crazy, scary movie. So they’re two very different kids, but they come together and love comedy. They watch raunchy comedies like Step Brothers and all the ones that they probably shouldn’t be watching. We had to explain the sperm in the hair in There’s Something About Mary. That was the film that made them wet their pants. I kind of like that we have those discussions because it leads to other things. So as long as it’s within a range, I’m pretty happy.

What did you see when you were really young that traumatized you?

Oh man—all of them. That’s what I cry tears over now as an adult. I lost that feeling. That’s the worst part of growing up, and worrying about taxes and all of this other mundane shit in life. That’s scary. Watching friends die on Facebook every few weeks. All of that stuff is scary. That’s the new horror. For me as a kid, it was Burnt Offerings and Satan’s Triangle. Hell yeah, man. Those are the films that traumatized me for years, Satan’s Triangle especially with Doug McClure. You couldn’t find that film for so long. It was this memory of a ABC TV movie of the week. There are certain images from the thing that haunted me. The ending had this holy shit twist with the devil actually being in the helicopter picking up the survivor and this final moment where he turns to the camera. That’s haunted me for 40 years or more. I finally got it on 16mm like, “I got it! I got the holy grail!” Then I watched it like, “This is a piece of shit! How was I ever scared of this thing?” You can never go back to the nostalgia of all those seminal moments for you as a moviegoer. But yeah, I’ve got synapses full of vivid flash frames of stuff that terrified me as a kid. Now my mantra is, “Don’t go back. Treasure the memory. House it and contain it. When you create, try to make those moments again for a new generation.” If you can pull one of those off in your lifetime, you’ve done something really special. That’s the goal. If you can house imagery for the ages that’s going to have an indent on a generation, your job is done.

What is your trajectory looking like right now? Do you feel more committed to directing?

I think the phrase was “one and done” during Come to Daddy. But no, it was a complete recharge for me. I felt like I had been coasting, doing what I knew was comfortable. I had fun doing all the other things that I do in the industry, but it was zero challenge. It felt like being on a bungee, but you’re lying at the bottom and there’s no cliff. Doing the film felt like I’d gone back on top of the cliff again and staring down into the abyss. That whole nervousness came back: “This is what living feels like again.” You get bogged down with suburbia and kids and marriage. Everything starts to even out and it becomes this very safe environment. So the film to me was terrifying, scary and I loved every second of it. It wasn’t even the creative aspect of it. It was how fucking shit and crazy it felt. It was like getting an electric shock to the system and that’s super addictive. It’s like, “Now I know why people go hang gliding and why people keep climbing those mountains without ropes.” It’s because you gotta keep that heart pumping as you get older, when you start seeing people drop away. [laughs] It reminds you that life’s really short. You don’t wanna go out with regrets. My biggest regret would be to fail the kid that I made promises to who was that filmmaker. It’s like, “What happened to him?” He’s setting up films for every other director, but he stopped. I suddenly feel like I’m 12 years old again and wanna keep going.

I’m working with Toby Harvard again. I don’t want to find scripts from outside sources. I have no interest in someone saying, “Here’s Silent Night, Deadly Night Part 5!” It’s gotta be something that’s personally connected to me again, and I don’t think I could even make anything that isn’t. I went to Toby again and said, “I had something else weird happen to me when I was young.” [laughs] We came up with a manifesto of ideas about this occurrence and it turned into a 70-page document. From that, he’s gone off and made a first draft and it looks like something is gonna come out of that. That’s probably what I’m gonna focus on instead of trying to do too many things. But I’m also producing other people’s projects as well so I’ve still got that bubbling along.

Did you ever toy with the idea of turning your Otago experience into a genre film?

[laughs] It’s kinda been done: Animal House. I felt like Bluto. But yeah, there were a lot of strange happenings. There were guys from the army in there that year. Someone died in the hostel. There are nutso stories actually. You could have a crazy first-year freshman going into the hell zone. The hostel was part of an asylum so at certain times there were patients walking around the corridors at night in our actual living quarters.

Yikes.

Yeah, like a Japanese ghost story. But no, this new one I’m working on is more from when I was bit older and I got caught up in something very weird.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments