The battle between artistic intention and the workman’s imperative to keep food on the table is always there.

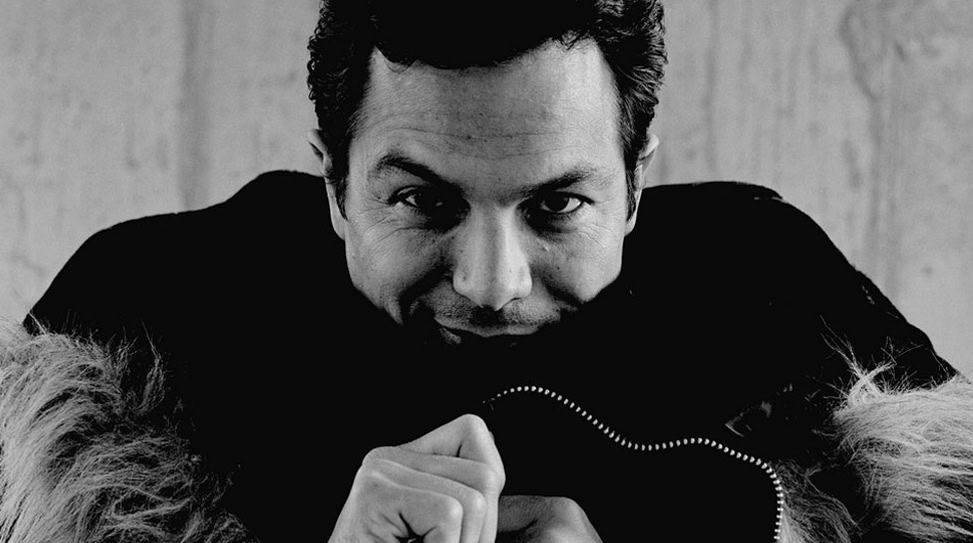

Benjamin Bratt has moved freely in a body of work that spans comedy to romance and action to drama in a career that includes such wide-reaching films as Demolition Man, Clear and Present Danger, Miss Congeniality, Traffic, Thumbsucker, Love in the Time of Cholera and Piñero. This is, of course, a partial list of his achievements, as the actor is no stranger to television, having appeared on Homicide: Life on the Street, E-Ring, The Cleaner and Modern Family, not to mention his decade-long involvement with Law & Order as Detective Rey Curtis.

In his latest film, a coming-of-age story that weaves its cultural themes into the narrative without coming off too preachy, Anita Doron’s The Lesser Blessed centers on Larry, a teenager in Canada’s Northwest Territories, whose First Nations heritage is far from the only thing setting him apart from his peers. Larry stands out among his mostly white schoolmates, but is less troubled by race than by scars–both the ones covering his torso and the psychic reminders of the abusive father who evidently put them there. Bratt plays his mother’s boyfriend and newfound father figure.

The Lesser Blessed finds its nationwide digital and DVD release on June 25.

Can you recall any lasting memories or piercing influences that might have informed your desire to become an actor early on?

Ironically, as a kid, I never considered acting as a possibility. Although I watched a lot of films as a child, everything from Old Yeller and The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes to The Godfather films and The French Connection, it was something that other people were lucky enough to do… Not me or anyone I knew. As a kid growing up in the ’70s, I watched a lot of films, everything really. On most weekends, you would find us at the drive-in. My mom would pile us into a station wagon and we’d go see films that were entirely inappropriate for 5 to 12 year olds, but what an education!

Did you look up to anyone in particular in the movies?

I grew up watching a generation of actors that will never be matched again. Gene Hackman, Dustin Hoffman, Robert Duvall, Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, Clint Eastwood, Paul Newman… There was John Wayne, Michael Caine, Sean Connery, Charles Bronson, Bruce Lee, Chief Dan George, Steve McQueen, Charlton Heston, Warren Beatty, Richard Pryor, and so on.

What was your entry into the business like and what did your parents make of it at the time?

My grandfather, George Bratt, was a professional actor on Broadway back in the 1920s as part of a group called the Grand Street Follies. On some level, it was my father’s idea that compelled me into it, which is interesting when you realize that I grew up with his workman’s sensibility when it came to making a living. He was a pragmatic union man and it was simply not a practical thing to do, to go off and study to become an actor. So, I was also encouraged to get my journeyman’s card in a trade union before going off on the artistic path. Of course, I blew that off and here we are…

You have many siblings, a big family. What was that dynamic like growing up and how do you think something like that shaped you as a person?

The truth is, my extended family is a complicated, lovely mess. There were many marriages and, as a result, I have many siblings, some blood-related and others that are not. There are some 14 in total through my father’s relationships and he’s not even Latin! The result is that I understand most families, large or small, have their own set of dynamics, some healthy and some not so much. I have come to realize that where there is love, there is not always peace, and that sometimes, you have to accept that fact… In my family, we all learned how to be diplomatic, how to share, and how to negotiate through hardship with reliance on one another. That remains the case today.

How did The Lesser Blessed come to you and what were your early impressions of the script?

It came in the typical way via an offer through my agent. It was accompanied by a personal note from director Anita Doron, who liked what I did in Piñero. It was an entirely thoughtful, though ultimately unnecessary, gesture. You see, as I began reading the script, it was immediately apparent that it was the work of a true artist. It was at once beautiful, raw, and painfully familiar with the awkward, often bittersweet, business of growing up as a teen. I was so startled by its humanity I had to write Anita a letter in return and tell her I would do her film no matter what.

Heritage is a big theme coursing through this film and it’s something very important to you in your personal life as well from what I can gather. Was that a big draw for you?

Yes, it was. It was both a revelation and a relief to read something this starkly beautiful, a story that captures the essence of what it is to be young and in the throes of feeling so isolated. Only in this case, it’s seen through the eyes of a Dogrib tribal kid. It was very courageous of Anita to take this on. The coming-of-age journey of a teenage outsider is a familiar trope, but I had never seen it done with such brutal and tender honesty, let alone from a native First Nations perspective. I loved that Larry’s story–his entire world–was so culturally specific, yet utterly universal in its depiction of teenage angst and disconnection.

What kind of comparisons did you make between the film and Richard Van Camp’s novel, which the film is adapted from?

Well, for starters, the novel is kind of a masterpiece. He nails the delicate balance between heartbreak and wry self-awareness. Larry is like an Indian Holden Caulfield. Van Camp’s protagonist kills you with that familiar desperation to belong, even as he makes us laugh at his hapless efforts to fit in. Anita’s script elegantly captured that same sense of knowing, which takes the material much deeper than the fart jokes and boner references that typically litter this kind of terrain. Both the film and the novel share the ability to make you laugh out loud, even as they shake you to the core when you discover the wrenching truth about Larry’s secret.

What kind of conversations did you share with Anita at the beginning?

Anita possesses an artist’s spirit and it was very easy to get on the same page with her. She had an unusual upbringing and, though worlds away from the Northwest Territories, she understood that it took a skewed approach to this kind of material to make it work. And what an eye… She has a knack for finding physical beauty even when it’s not immediately apparent. There are images in the film that are now indelibly imprinted on my brain. Just unforgettable.

Are you very structured in your process when you build a character?

I’m more of an instinctual performer. Of course, I also rely on technique and the research that goes along with a specific role like Jed, but that’s not what I’m thinking about when I get on a set. I do like to rehearse, though. That has always been a part of the process. It’s a chance to feel out the other actors and get in sync with each other and the director before the cameras roll.

Did anything surprise you on set?

Oh, hell yes. Anita wanted to shoot the rehearsals on my first day and it was my biggest day with a three-page monologue. I must confess, it stressed me out badly. But I just rolled with it and hoped that it would all work out, and it did. It’s a recent and more commonly occurring thing to find directors who prefer to shoot the rehearsals. I think part of it is a desire to capture “magic” in the off chance that something magical actually occurs. But it’s also a result of economics and the pressures on filmmakers in the independent sphere to make their page count. And I get it, having produced two low-budget indies with my brother Peter. Film work used to give you the luxury of time on a set, but that’s no longer the case. The difference between a TV schedule and a small budgeted film’s schedule is pretty much the same these days.

What kinds of roles are you interested in pursuing nowadays?

Frankly, when it comes to deciding what to do next, the reasons vary. I think all actors wish for the luxury of being able to pick and choose from the best material out there, but alas, that has never been my lot. I’ve done many films for love–that is to say, for no money–and I have also done jobs that simply pay the bills. Everything changes when you have children and the practical decisions must be weighed alongside artistic ones. That’s my reality. Of course, this is an ongoing, internal struggle for me. The battle between artistic intention and the workman’s imperative to keep food on the table is always there.

Not many actors out there are willing to admit that.

Listen, a close friend of mine is fond of saying, “There’s no shame in making an honest living,” and he’s right at the end of the day. I have to remind myself of that every once in a while. At this stage of my life, it feels like I have found a semblance of balance, but even that feels tentative in the face of how the business is changing. The little gems are harder to find and there are more of us vying for the same roles because there are less independent films being made. It’s a much different world than it was even 10 years ago and I find myself having to be more open-minded than ever before if I want to continue working as an actor.

You have two animated features coming up: Despicable Me 2 and Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2. Do you enjoy voice work?

Voice work is the shiznit. I love it, truly. If I could only do that for the rest of my professional days, I would be just fine with that. It’s incredibly freeing to go into a studio, just cut it all loose, and get a little wacky. The only thing I would miss, however, is working with other actors face-to-face. You don’t get that in an animated film, so it’s an isolating process. I love acting and I love actors, so I would miss that… Actually, I take it all back. I’ll stick with what I have, thank you very much.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

1 Comment