The unfortunate reality is that, so often, we as the others are maimed as the minority groups. But it’s a lie. It’s another lie that plays into the system of white supremacy.

1995 was still an archaic time for the LGBTQ community. It was right around “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Same-sex marriage was nowhere near legal. It was three years short of Matthew Shepard’s murder. To further set the stage, Ellen DeGeneres wouldn’t come out on the cover of Time magazine until 1997, which subsequently all but destroyed her career. All of this disturbance, and so much more, is baked into the DNA of Kurtis David Harder’s ambitious horror movie Spiral, which plays out in that one backwards year, in a fictitious exurban town—anyplace, America.

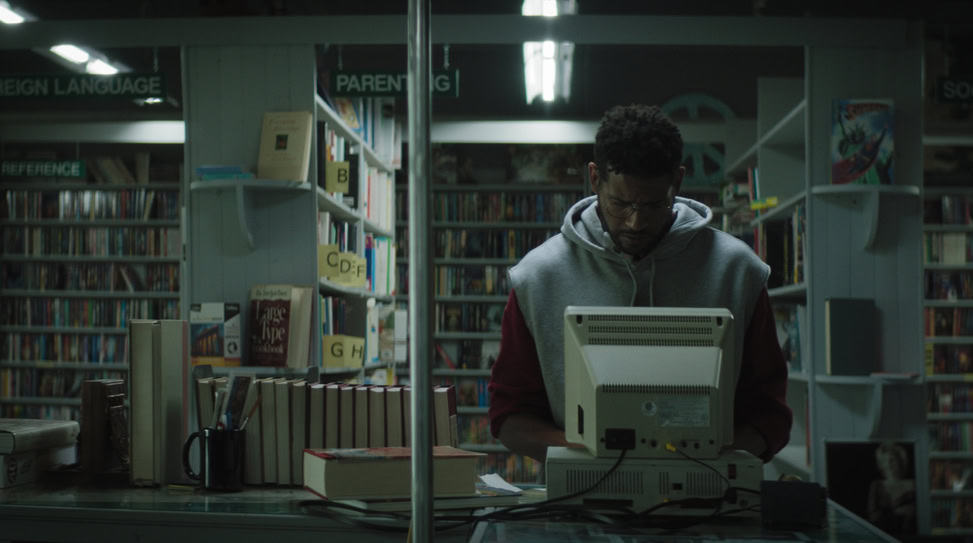

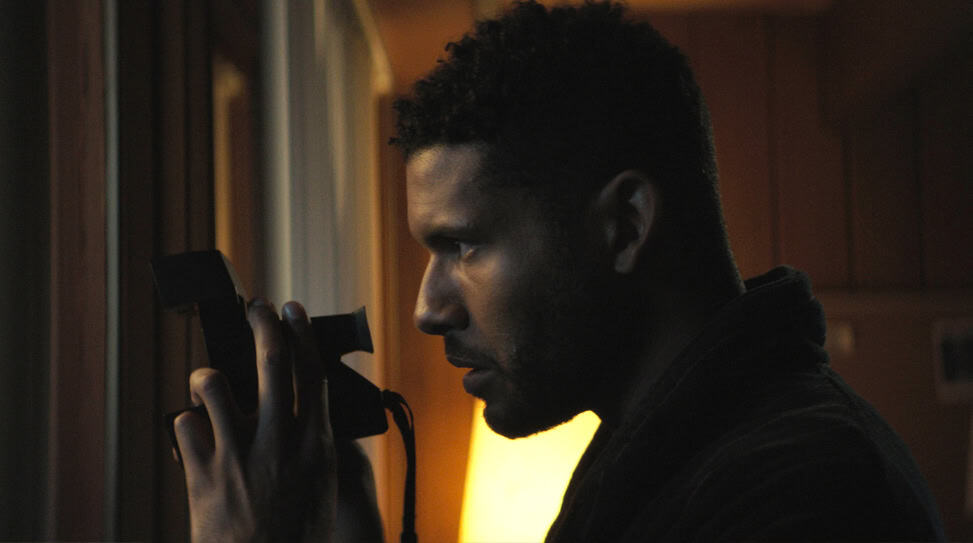

Malik (Jeffrey Bowyer-Chapman) and his recently out partner Aaron (Ari Cohen), along with the latter’s teenage daughter Kayla (Jennifer Laporte) from a previous hetero marriage, are new arrivals in Rusty Creek, having left Chicago behind for a quieter life. On the drive in, a bird flies into their windshield, foreshadowing the tragedies that await them. Upon settling into their new home, casual racism is brought to their doorstep almost instantaneously: unnaturally sunny neighbor Tiffany (Chandra West) drops by, and mistakes Malik for Aaron’s hired help. But Aaron doesn’t take to Malik’s mistrust of the locals, and actually seems to enjoy bedding with the community. For Malik, who presumably lived as an openly gay man ever since a violent hate crime devastated his teenage years—this is shown in flashbacks—coming home to find a homophobic slur daubed on their living room wall only exacerbates his hovering paranoia. Now everywhere he looks, there is danger and evil intentions, and undercurrents of contempt and manipulation in every interaction. As a queer person of color, he is a double anomaly, which, understandably, weighs on him greatly. If that weren’t enough, things are made worse by other inexplicable disturbances that pile up. Malik begins to hear thumping noises around the house at night. An old man keeps showing up outside their home, watching them with uncertain motives. Then one night, he spies a group of neighbors across the street, swaying in a circle in a kind of diabolical ritual, further confirming that something unmistakably sinister is afoot, which cannot go ignored any longer.

Horror films commonly lack any real queer representation. Spiral, a film that clings tightly to Bowyer-Chapman—a wise choice given the strength of his performance—wants to rectify this oversight. His portrayal of somebody who goes from an out-and-proud gay man to a self-doubting person backtracking on his own words of wisdom is both dazzling and heartbreaking. It’s difficult to tear your eyes away from it. The Canadian actor, who you might recognize from UnREAL, American Horror Story and as a main judge on Canada’s Drag Race, devours every scene.

It wasn’t that long ago—1995, for instance—that the idea to have a character like Malik as the focal point of a horror movie, or any genre, would’ve been but a dream. There was similarly a time when LGBTQ characters were not once played by LGBTQ actors. The horror genre, hopefully, finds itself in a new era with movies like Spiral. Once locked doors, hopefully, are now wide open.

Spiral is available to view on Shudder in the U.S., the UK, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand.

Where are you Zooming in from, Jeffrey? Are you in Los Angeles?

Yes, I’m at home.

Are you bicoastal these days?

I was for years, going back and forth between New York and Los Angeles. But I’ve been pretty much stationed in Los Angeles for the past two to three years solid.

How are things in L.A.? I haven’t been on the ground for awhile. I know things are different.

Oh gosh, in many ways it’s the best place to be and in many ways it’s the worst place to be. I have reference because I have friends who are in New York obviously, and my family is all in Canada. Weather-wise, my family had to go through the first couple of months of quarantine when it was still freezing cold with snow outside so they couldn’t even leave the house. In New York, you’re trapped in your one-bedroom or two-bedroom or studio apartment with not much freedom or space. Here in Los Angeles, as challenging as it’s been, in contrast, it’s a good place to be. I have my house, I have my backyard, it’s beautiful weather. I just wish people would get their shit together and start wearing masks so we can get through this first wave before we go into the second wave. [laughs] We’re evolving and adapting day by day.

Midway through watching Spiral, I was already emailing the publicist back: “I need to talk to Jeffrey.” We never see characters like this—to this day. It’s also clear to me that activism and acting is inextricably tied for you. Imagine my surprise when I learned that Malik had originally been written to be white before you gave the filmmakers your note that he should be anything but. Just how different was Malik before you came along?

Obviously, I can’t predict what could have been or what it would have been, but yes, I believe that the character would’ve remained white had I not given the producers and writers [Colin Minihan and John Poliquin], who are two great friends of mine, that note. I thought it would be that much more interesting to bring in the intersections of otherness and make this character a person of color. I wasn’t pitching myself. I didn’t even necessarily mean for the character to be black specifically. As you know as a person of color, our lived experiences and the way we navigate our way through the world is much different than for white folk. The character really didn’t change that drastically, truthfully. I don’t think much at all honestly, based on what we actually shot compared to the original script I first read. It was a couple of lines here and there. There is a line that Malik says when Aaron is normalizing heteronormativity. Malik makes a comment about Aaron being like an “Uncle Tom for gay people.” That’s in reference to a historical black character, Uncle Tom, who would essentially sell out other black folk—escaped slaves or runaway slaves. Aside from that, the character and the story stayed true to what it was. It was just the fact that I was so infused in this character and I happened to be covered in black skin. That was the one major difference.

That was probably the single most important note anybody could’ve given the film. It’s a completely different movie. With one stroke of the pen, the movie is socially conscious. It’s alive with meaning and complexity. Malik is the movie’s life force. I think something that might be difficult to fully grasp, too, if you’re not a person of color or have any otherness about you is just how important it is to see yourself in the media. I seldom saw Asian people anywhere, let alone on the movie screen, growing up in America. It’s important, and it’s not just about you identifying with somebody who looks like you. It’s also about everybody else being witness to your representation in the media. We exist and we’ve always been here.

Absolutely. Because we can see now—even more so now than six months ago—that the truth of the matter is, this world is built on a foundation of white supremacy. It’s a reminder to folk through art and through film that, like you said, it’s not only the importance of representation in the sense that we as a people of color turn on the television and see reflections of ourselves. It’s a reminder to the rest of the world that we’re here, too, and we always have been. With the entertainment industry being a part of the machine of white supremacy and white privilege, and all that goes along with it, we’ve been completely erased from film history. You look back at period pieces and all you see are white folks. You don’t even have to look at period pieces. You can look at shows like Friends or modern-day pieces set in multicultural places like New York City and only see white people. We’re very blessed to be finally in a time where at least some semblance of reality is being infused into film.

It’s funny you bring up Friends. I loved that show—I still love that show—but I can honestly only recall the show playing the diversity card with Aisha Tyler and Ross’ girlfriend Julie, and how many seasons did that show go on for?

Right, and Friends is essentially—I don’t want to say a knockoff, but—a knockoff of Living Single, which had an all-black cast living in Brooklyn. It’s the exact same storyline. It’s the exact same dynamic with all black folk. Then NBCUniversal came along and whitewashed the story and it became an international sensation.

When was the first time you saw yourself reflected in the mainstream media?

[laughs] Do you know what’s hilarious? I ask that question on my podcast all the time to my guests and I’m stumped as your sitting here asking me. I think RuPaul in To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar is one of the first examples I have of a black queer man in film. But truthfully, I guess the first time I ever felt seen or felt like I could see myself in a character was on the Buffy the Vampire Slayer series. Not only was it Sarah Michelle Gellar’s character that I felt I could relate to and resonated with, it was her use of gymnastics, and her sass and wit. Die Hard or any other big action movie where Bruce Willis is bumbling around with his big muscles and bazookas—I couldn’t relate to that. But Sarah Michelle Gellar doing back handsprings and kicking a bad guy in the face? I was like, “Oh I could do that.” And then you have her tribe of Scoobies. The weirdos. The odd ones out. The queer kids, even if they weren’t explicitly queer until later on in the series. That’s really the first time I felt like I saw people like me reflected on television.

From what I understand, you guys filmed Spiral an hour out from where you actually grew up in Canada. I wonder if there was a curiosity in you to return to that place with the life experience and knowledge you have now, to maybe resolve something—to come full circle.

That’s interesting. I learned a lot from the experience, going back to the proverbial scene of the crime where I was raised. I was adopted as a baby. I was raised in white spaces. My whole family was white. I was the only person of color in my family, in my school, in my town. I was the only queer-identifying person in my community so I always stood out. There was always all eyes on me. In that, I could relate to Malik’s experience, absolutely. It’s what I experience to this day, where people tend to create or form opinions about me based on their prejudice or based on whatever it may be, based on one sliver or one tiny aspect of my personality they can glob onto and think that’s the entirety of me. Being gaslit. My experiences of racism or homophobia, whether they’re subtle or blatant right in my face. Having been minimized when I tried to express how I’m feeling to my friends and family around me. All of that I could relate to, and all of that is extraordinarily painful as you know as an other, as a person of color.

I didn’t know when they asked me to do the film that we would be shooting in a place that’s an hour away from where I grew up. It was effortless to emotionally go back to that place where I left off, where I was a teenager and living in an environment of oppression, violent homophobia and racism. Although I’ve done a lot of work on myself over the years through therapy, and developing a close relationship with my mother and my family, and really painting a clear picture of what my experience was like at that time, it was effortless to go back into that emotional place where Malik lived. It wasn’t easy though. It made it that much harder actually, filming where we were filming because normally when I wrap at the end of the day, I can go home and leave the character and the story on set. But we were filming 21 days and I filmed 20 out of those 21 days. I was so deeply immersed in it. When I left the set and still in that emotional place of feeling so raw, I would be driving through the same streets and the same country roads that I drove down when I was a kid, feeling that same sense of terror and fear. That certainly added to, unquestionably, who Malik ended up being at the end of the day on film. But I couldn’t have anticipated it.

The Emmys were just handed out. It was historic because the majority of the acting awards went to black performers. Momentous change and progress are slow going, aren’t they?

Yeah, definitely. I’m so proud of Zendaya. I’m obsessed with Euphoria. Watchmen is one of the best shows on television. It’s only had one season and I’m so glad that they’re going to go past that. It’s such a bold choice and the right move. And Ru making history with winning Best Reality TV Show Host five years in a row—he set a record. I’m so, so proud. It’s a moment for black recognition and black excellence.

I noticed a lot of reviews have been written up about Spiral being “queer-horror.” They mean well obviously, but it’s silly if you start thinking about the possibility of “straight-horror.” I think most people would find that totally ridiculous. I still remember talking to Xavier Dolan after he won the Queer Palm for Laurence Anyways at the Cannes Film Festival. He hated it because that award othered him and his movie. What are your feelings on that kind of label?

I wouldn’t be the first one to label it queer-horror, that’s for sure. But also, everything I do is prefaced with either my blackness or my queerness so it’s something that I’ve unfortunately become accustomed to. It is not only wildly unnecessary, it’s the media and critics who hold a tremendous amount of influence. I think it’s wildly irresponsible. Knowing that you’ll be setting the tone and laying out the foundation for how other people view a said project, you have a responsibility to be mindful of how you present the project to the world. Clearly, there’s nothing wrong, there’s nothing to be ashamed of, and there is no reason for us to play small to the fact that it is a queer project by queer people for queer people. But it’s also for everybody. It’s with everything, dude, you know? Anything that’s straight and white and cisgendered is going to be labeled as what it is, and anything that’s not straight or white or cisgendered is going to be prefaced with “the black project,” “the queer project,” “the Asian project,” “the trans project”—whatever the “other” project is. The unfortunate reality is that, so often, we as the others are maimed as the minority groups. But it’s a lie. It’s another lie that plays into the system of white supremacy. We as a people of color are not the minority on this planet. We as queer people are on the spectrum of sexuality and are not the minority on this planet. As long as we continue to label ourselves as being the other, we’re not really making any strides towards just overall inclusivity.

Malik says in the movie: “People don’t change. They just get better at hiding how they feel.” Where do you align with what he says there? Do you think there are a lot of fakers out there?

[laughs] That’s an interesting way of putting it! I think there are a lot of people out there who are very inauthentic and a lot of people who jump onto bandwagons, good or bad, so that they aren’t the ones who are vilified. Whether or not they actually believe in what it is they’re saying on the issue or about the person they’re piling onto—it doesn’t matter. It’s a sheep mentality, and people just don’t want to face the same ridicule or discrimination or oppression as the person they’re piling onto. How do I relate to what Malik says? I see it everywhere, unfortunately. Living in the United States of America, people naively think that we’ve come so far by having had elected a black president and that racism was a thing of the past. But as we’ve seen over these past four years, nothing could be further from the truth. I think of this researcher who focuses on shame and courage and vulnerability—her name is Brené Brown—and she says that shame is the most ineffective social justice tool. Meanwhile, other people’s perspective in the media has been that there needs to be a new wave of shame in America, that we need to start shaming people for being blatantly homophobic or racist. That’s not going to solve or help or fix anything, if we’re just putting a Band-Aid on the issue and having people zip their mouths shut. They will keep their hate and their vitriol to themselves, if that’s genuinely how they’re still feeling in their heart’s core. I don’t necessarily know what the solution is. I just think that sunlight is the best disinfectant. As long as we can bring all of these issues to the light of day and have mindful conversations about it, I think it’s the only way we can get to a place where people actually do change the way that they feel. It’s easy to change the way people think, but you have to change how people feel.

I love what you’re doing with Conversations with Others. You obviously have your subjects who are pouring their hearts out and also people listening in who get a lot out of these curated conversations. How has it been fulfilling for you? Do you feel very changed by it?

Thank you so much for listening, first off. That’s very kind of you and it means so much. It is probably the thing that I’m most proud of in my career, and it’s not a huge project. I don’t even know how many people listen in, truthfully. I just do it for myself. It’s a project that stemmed from me being on RuPaul’s podcast What’s the Tee? years ago, after my first episode of RuPaul’s Drag Race and the conversation Ru and I had, which is based around emotional mindfulness and spirituality. We both very much speak the same language in that respect. Ru and his producer asked me if I wanted to have my own show, to create my own show, to have a platform to continue to do the same. Truthfully, these conversations that I have on my show are the same conversations I have with my dear friends. I’ve always wanted to just sticker a microphone on them and have these memories captured so that I can go back to them for reference years from now. I love this show. I love the platform that I’ve created to have these very open and candid conversations on everything from sexuality and spirituality to racism and oppressions and everything in between. It’s literally no holds barred. I know that the most growth that I’ve had personally has come from hearing the lived experiences of others, whether that’s through reading memoirs or autobiographies. Especially as a young, queer person of color growing up in a world where there was nobody like me around me, I really didn’t have any points of reference for what I was experiencing. I couldn’t look to references in the same way that my siblings and friends could because they a pathway out for them—a blueprint. Their guidebook was in a different language than my guidebook. So that’s where the show really came from. It’s from my love of Maya Angelou and James Baldwin and all of these extraordinary literary greats who were brave enough to have the audacity to live authentically and to share their stories with the world—the bad, the ugly, and the beautiful. They were these extraordinary human beings, these phenomenal human beings, who we put on a pedestal. What they achieved is like a once-in-a-lifetime thing that no one else could even dream or dare to aspire to, but when you break down their stories and you hear it from their own mouths, you realize that they’re just regular folks, regular people like you and me who’ve made a shit ton of mistakes along their journey. But they learned lessons from the steps they took and applied it to their next situation, the next situation, and eventually became a stronger, more resilient, well-rounded, thoughtful, mindful human beings. That’s my intention with this show. And yes, I have grown tremendously from having the blessing and the privilege of getting to hold a safe space for all of my guests to come on and share their lived experiences.

Like yourself, your guests are outspoken and informed individuals who freely speak their minds. There’s something disturbing about the interviews that we so often see in magazines —“the fluff pieces.” There’s something unsettling about going into press junkets where talent are shuttled in and out of hotel suites, and you so often get canned responses. You can literally see that they’re scared to say what’s really on their minds, for whatever reason. That’s why something like Conversations with Others is so worth tuning into. It’s real talk.

I appreciate that, and like I said, the foundation of my show came from RuPaul’s podcast where he very much does the same. It was the first time I ever had that experience, which is the opposite of what you’re saying: being an actor who does press junkets all the time and having to self-edit. Being in an environment like that with Ru, where he really asks the questions that I ask and have the kind of conversations that I like to have, it was the first time I ever felt like I could truly show the depths and the truths of who I am in the media.

What do you think would be the next leap forward for representation on TV and in film?

It’s such a complex question, but a simple question at the same time. The simple answer is: to be able to turn on our TVs and see our same stories on the major networks—ABC, NBC, CBS, FOX—above all of these white-centric sitcoms. It would be to see the white-centric shows infused with the shows of others, featuring differently able-bodied people, with trans-bodied people, with queer people, with people of color. I think Malik in Spiral and my suggestion to make him a black character is a great example. You can take the same story and task a different actor with a different color of skin, or whatever the different “thing” may be, and have it be just as relevant, if not more so. I just want more opportunities across the board for everybody who’s not straight, cisgendered, and white. Even in acting classes and in the theatre, for example, when actors train, once again, it’s a system that’s run by white supremacy. You’re constantly getting material by Shakespeare, or off-Broadway or Broadway plays that are white-centric stories and straight-centered, cisgendered stories. I only took a handful of acting classes because all of the material that was given for me to study and to perform was that, and I knew that I had zero interest in playing that. That wasn’t going to help me or benefit me in my real-world career because I wasn’t going to be going in for Captain America. I was going to go in for queer characters of color. Championing characters of mindfulness and inclusion is across the board and obviously the goal and the intention for all of us, I hope. I don’t know how that’s going to happen, but I hope that it’s just a matter of people being truly more mindful and not just being a performative ally—actually taking steps towards creating an equal environment for all of us.

Since they’re rebooting everything, maybe you could be the next Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

I would love that. I think they are in the process of rebooting it. I would gladly jump onboard. The creator of UnReal [Marti Noxon] was the executive producer of Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments