Pleasure and cinema are tied together, and it’s complex. It’s not as simple as thinking that anything a man looks at is beautiful and is necessarily repressive.

It’s a rare opportunity and quite novel, and not necessarily that calculated on our part, when you’re able to check in with a filmmaker, from film-to-film, from their debut towards an open horizon.

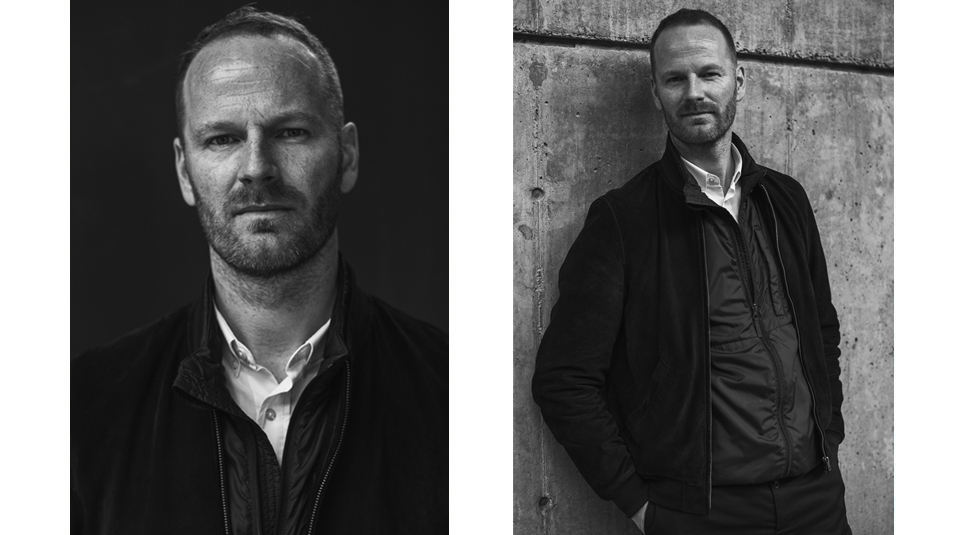

Anthem’s history with Joachim Trier goes back to 2008: We interviewed the auteur about his first feature Reprise. Our follow-up came in 2011 at Cannes for Oslo, August 31st, which played in the Un Certain Regard sidebar. In 2015, Trier sat down with us at the Carlton Hotel in Cannes to discuss his third entry, Louder Than Bombs, which marked his first time competing for the Palme d’Or, newly in his 40s. This week, we met up with the filmmaker in Manhattan to discuss his latest effort, Thelma, and what’s to come, including his upcoming documentary about Edvard Munch.

In Thelma, we first meet Trier’s titular protagonist as a young girl (Grethe Eltervåg), out hunting in a remote stretch with her father Trond (Henrik Rafaelsen). Thelma stands frozen at the sight of a deer and Trond aims his rifle at her head. He doesn’t pull the trigger, but the temptation is there.

A decade after that disconcerting prologue, we’re reintroduced to Thelma (Eili Harboe) as a shy young woman heading off to university in Oslo. It’s a move that puts her overprotective and ultra-religious parents on edge. Trond and his wheelchair-bound wife Unni (Ellen Dorrit Petersen) have this exasperating habit of checking up on Thelma online, monitoring her lecture timetables and Facebook friend-acceptances. One day, Thelma exchanges a warm smile with a fellow student named Anja (Kaya Wilkins), and within seconds, she’s thrown into a convulsive seizure, which happens to coincide with a flock of birds crashing into the library windows. Their primal attraction, needless to say, stands in direct conflict with Thelma’s evangelical upbringing. Trier continues to marshal the intractable compulsions of Thelma’s self-discovery with a supernatural charge, like in her ability to make people vanish into thin air without a trace. There are other set pieces of similar impact in this script Trier co-wrote with his regular screenwriting partner, Eskil Vogt, including an MRI scene so visually assaultive that the film smartly comes with a warning for epileptic viewers.

Thelma is now playing in select theaters.

You’ve been called a visionary for a long time, but looking back, that almost feels prophetic because Thelma scales so much heavier in scope compared to your previous films. You once brought up Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons and how François Truffaut said watching that film is like taking ten gallons of water and pouring it into a pint glass.

[Laughs] I can’t believe you remember me saying that!

Isn’t that what you’re doing here, essentially?

Yeah, in a way, I wanted to try something else. This is my fourth film and I wanted to take a risk. I wanted to liberate us. I wanted to do something visually different. We deal with genre elements, not to repeat them, but to see if we can sort of allow ourselves different types of imagery and a different structural thing cinematically. It’s about playing with suspense and with some scenes that are driven by space from a visual perspective, and being inspired by the Hitchcockian tradition, rather than just go for [Michelangelo] Antonioni again, you know? [Laughs] We’re playing around here. At the same time, we went back to character-driven storytelling, as always. We couldn’t leave it and I was interested in it. But I guess we started out by thinking we would make more of a horror film. We ended up not being so interested in blood and guts, and jump scares. We were far more interested in internal horror, with the body and the self as the horror in the story.

Louder Than Bombs was your first English-language film. Is there something to be said about your return to working in Norway? Does it feel more organic, just by the nature of things?

I guess we were shooting quick again. There was this feeling that we were writing and then going on set quickly. There’s this shorthand with shooting in Norway, with the locations. But Louder Than Bombs felt as personal as anything else I ever did. Yes, it was in English, but I think there’s this misconception that foreign filmmakers should just stay in their own country. I think we should be allowed to travel. It was fun to go back to Norway and work with some mythological things: the woods and the birds and these mystical, Gothic themes that I hadn’t explored before. To do that in my own culture was fun as well because it drew me back to these childhood notions of fright, being in the woods as a kid. In Norway, there’s a different relationship to nature. On one level, it’s what we’re proud of, and I’m an urban person. You walk in nature with your family on holidays. At the same time, with these fairytales that we grew up with, nature can also be scary and dark and cold and just difficult. Nature is always filled with mythical characters in fairytales. They’re very representative of the emotions and sexuality of the 1800s bourgeoisie culture. They’re often witches or temptresses of various shapes and forms out in the woods. So I’m thinking in a sort of modern context. We inverted some of those things to create a more feminist fable or a more empowering story for the young woman, which was a fun way to play around with those tropes.

I don’t think I’ve ever asked you this: Did you grow up in a very religious household? Those religious themes and imagery are paramount in Thelma, as much as repressed sexuality.

I didn’t! I come from a very liberal, atheistic household. But I’ve always been curious about things. I long for the mystery world of childhood. The film starts with a scene of little Thelma as a six-year-old. She’s walking on water, looking down into the transparent ice at the fish. That’s the kind of wonder you have as a child, and we don’t separate the magical and the real. That’s something that I’m fascinated by. What I don’t like is when religion starts defining power structures that function as repressive strategies, particularly against people wanting to love who they want to love and towards women. We still have that at play in most societies around the world. So I felt okay about talking about that. That’s important to talk about, even though I’m not religious myself.

Thelma explores film’s ability to show something that is very human and relatable in a supernatural framework, much like Carrie did, I guess. I’m curious about where the conceptual fragments came from, like the visuals of spontaneous human combustion on a lake and the fear of drowning in a swimming pool without a surface to come back to for air.

I think it’s just imagination. You just trust that what your subconscious throws up in the process of creativity probably has something valuable to it. It’s something that you explore, without necessarily trying to rationalize it in the process. That was a very important aspect of making this.

What about this idea of Thelma literally wishing people out of existence? It’s harrowing.

Well, [Eskil Vogt and I] started not knowing exactly what the evil or the supernatural was going to be at the beginning of the writing process. But we realized what we’re really concerned with is the internal dynamics of humans in all of our work. We were reminded a little bit of [Andrei] Tarkovsky. Solaris, and even Stalker, has this notion of society of our true will. Then we started reading some Aleister Crowley and the book on dilemma. “Dilemma” is an old Greek word that means “the true will.” From there, we came up with the character of Thelma—”Now we’ll call it Thelma“—and went from there. It’s always this sense of our society: It’s this psychological dynamic and the fact that our mind is continually negotiating between the fantastical and the internal, and the endlessness of our passions and needs. We’re always constricted by society and our own sense of properness. To make that into a horror film, for us, was an enticing idea.

What’s there to say about your male gaze with Thelma? Specifically, we see Thelma getting high and then touching herself as a snake writhes into her mouth. At the very least, do you think about how that might be a reflection on you, a male filmmaker, when you’re writing it?

I try not to create art from a place of anxiety. I try not to hold back. I try to let my curiosities and my fascinations run free when I make movies. I’m locked into a character. I’m with Thelma. I’m trying to look with her, and as her. For that specific scene in the film, it’s very much about her anxiety and losing control of her body. A lot of what we see happening to her is very distressing. But in that moment, she feels pleasure. She feels that she’s allowing herself to be the beautiful girl and to be dealt in an almost masochistic way as a liberating thing. I think it’s a very clear sign of the suppression that she comes from. Then the aftermath of that moment is also very, very, very shameful for her. That’s the dynamic I’m so curious about. It’s the way that liberation and shame plays with each other in this film. So to answer your question, I don’t think I should limit myself in what I show, you know? I think there should be this freedom to images. But I know those discussions are going on. Ultimately, to follow that thought process, I’ll say that there are limits as to what you can do as an artist, depending on your age and your gender. I think that’s a very dangerous route. I think the film is ultimately so clearly on Thelma’s side. I would also suggest that—if people felt they want to attack it for that reason—most commercials and television and action movies show the legs of a woman when she walks up the staircase in a random scene, instead of showing her face. I mean, I understand the question. It’s relevant and we should talk about these things, but we should also be careful. Pleasure and cinema are tied together, and it’s complex. It’s not as simple as thinking that anything a man looks at is beautiful and is necessarily repressive.

There’s also something to be said about your love of snakes. I think filmmakers often get interrogated about things in a way that’s unfair because we live in such a triggering culture.

Yeah, that’s a good point, too. I’m fascinated by snakes, for real. This scene was also very inspired by manga and anime. I grew up reading a lot of Japanese comic books and some of them would deal with a lot of kinky and fascinating imagery of masochism, of repressed characters trying to express through that kind of fantasy. That’s an interesting tradition. What’s wrong with that?

I was actually surprised by how inexplicit Thelma and Anja’s courtship is in your film. It’s loving in the way that we don’t see enough of in cinema regarding gay relationships. It often feels like filmmakers want to make the sex teeter on “too much,” as if to warrant its existence. It’s complicated a lot in film. Why did you decide to explore a lesbian relationship?

To be very honest, that came very late in the process. Originally, in the early drafts, Thelma had a brother who’s gay and the father was very against that. That almost became more of a revenge plot on behalf of the brother. We’ve had a wave of young people killing themselves in Norway, from being shameful about being gay. We felt that was an awful thing to happen in our culture and wanted to talk about it. But then we spoke to this expert on epilepsy, one of the foremost doctors in the field in Northern Europe, about psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. He told us that a lot of these people, particularly women—70 percent of the cases involved women—are dealing with sexual anxiety or repressed childhood trauma. Then he asked me, “This girl that you’re making a story about: Am I to understand that she’s a lesbian?” [Laughs] We were like, “No…” But then we realized, “That would focus on the father/daughter relationship much more and we wouldn’t need the brother character.” Suddenly, things popped into place for us. That was a great moment. It actually came from the research we did on epilepsy, so it was rather paradoxical!

You did something in Thelma that echoes a formal decision previously seen in Louder Than Bombs. You introduce YouTube clips and still photographs, which we seldom see outside of documentary filmmaking. I remember Olivier Assayas did that in Personal Shopper as well.

I like to have different formats for sequences in my films. I guess there’s a tiny one in this film as well that deals with the stigmatization of female emotionality throughout history. It’s what we called “the witch” sequence where Thelma explores Joan of Arc and epilepsy in the film. So that was a little “essay speak” thing that we felt was interesting. That came out of our research more than anything because we didn’t want to throw it out. [Laughs] We wanted some of it in the film.

I like the idea that you can find people you create a shorthand with and collaborate with continuously. What makes those relationship work so well for you? There’s the loyalty factor.

Editors, the cinematographer, with the sound design, my co-writer—we’re a bunch of people who keep exploring stuff together and I think that’s really valuable, especially when you want to try different things as you move forward. We can then try to study new elements. For example, we did 200-plus CGI shots [for Thelma] and that takes a hell of a lot of time. We did it with animals, snakes, fire, ice, glass—difficult stuff that’s very, very easily recognizable for people and has to look real. And it was a mixture with fake snakes in the same scene, for example, so it was really tricky to balance the shots out with CGI. That was really challenging, but really fun as well.

Why did you decide to employ CinemaScope for the first time?

Cinemascope is fascinating—completely different lenses and format. I guess we’re being challenged in a good way from TV shows at the moment. We gotta prove our worth on the big screen, so we brought out the cool equipment this time. [Laughs] Honestly, it was also because it created this dynamic in the film with the visual concept: the very, very intimate and also claustrophobic images versus the very wide, almost agoraphobic or more paranoid, looking from afar, and big space images. The CinemaScope form helped us to emotionally express that.

So what’s your next chapter then?

That’s a good question… I don’t know yet. I’m just traveling with Thelma, which was completed just this August, so it’s pretty new still. I’m finishing up on a documentary that I’ve been doing about Edvard Munch by Christmas. Then we’re moving on and, hopefully, we’ll sit down and write this January. We’ll just go from there again, as always. That’s what you want to do.

Is that in-between-projects space scary for you?

I mean, it’s absolutely important. The privilege that I fight to sustain is making everything that I write. I don’t have a lost project yet, so it’s four for four. Even though it’s a big machine and there’s money involved, it’s our responsibility in cinema to express what we want to express, right here and now, and be sensitive to our contemporary times and see what comes out of that, aesthetically and thematically. So we’re gonna go into that. I look forward to it. I love being in the writing room with Eskil and exploring, watching movies and discussing, and trying out ideas.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments