Edvard Munch defined for us what it is to be Norwegian and Norwegian artists in a way. It comes from him somehow.

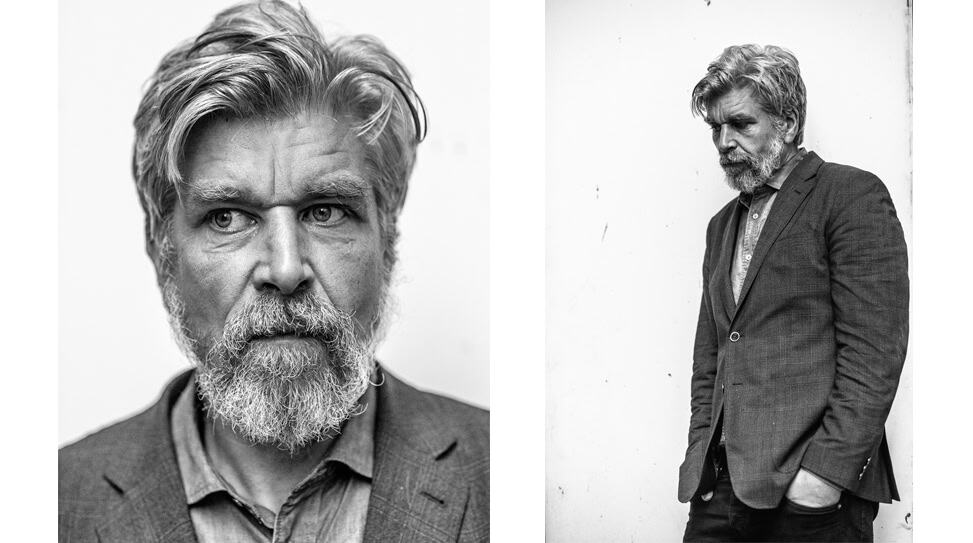

For Karl Ove Knausgård, the acclaimed Norwegian author behind the six-volume autobiographical novel My Struggle, no moment is too mundane to escape his notice. No memory is so distant that it can’t be recalled with the force of naked experience. In its opening pages, he looks at the roadmap that is his very face and asks, “What has engraved itself in my face?” The next 3,600 pages depicts a radically narrow world that looks inwards—one in which very little exists outside of himself.

The publication of Book One in 2009 turned into a scandal in Scandinavia as family members and old flames accused the writer of slander and betrayal. The controversy also turned Knausgård into a literary sensation: being hailed as one of the foremost practitioners of autofiction. When his work started making its way overseas, translated for the American market in 2012, critics underscored the author’s reputation for shamelessly exposing the most intimate details of his life. Book Six, the newly-released final volume in My Struggle, looks back on these controversies and strives to understand them. The closing tome stands apart from its predecessors as it zooms out from Knausgård’s enclosed domain, situating My Struggle against the backdrops of society and history.

Knausgård is now also the subject of Emil Trier’s documentary The Other Munch, which made its North American premiere in New York this week. The film explores the inner headspace of the author as he guest-curates an exhibition of paintings by Edvard Munch at Oslo’s Munch Museum. Co-director Joachim Trier—the Norwegian auteur behind Oslo, August 31st and a regular subject here at Anthem—appears onscreen alongside Knausgård as they visit several key locations from the iconic painter’s life. Searching for insights into Munch’s imagination, themes, and obsessions in a vastly influential oeuvre, the author’s interpretation of the artist is captivatingly unorthodox, and as a result, yields an engrossing double portrait of two of Norway’s most essential creative minds.

My Struggle: Book Six is available now via Archipelago Books.

Joachim [Trier] was joking that you “kidnapped” him in order to make this film. His brother Emil, of course, came onboard soon after. Why did you approach Joachim in the first place?

When I was invited to curate the exhibition, I proposed that we make a film to coincide with it. Joachim is the greatest Norwegian film director there is. His films are wonderful and, for me, it was an opportunity to just meet him. There’s something to do with Munch in his work as well, I think. So that is why. I didn’t know what it is to make a film. I thought maybe we do it on the mobile phone, and walk and talk a little bit. I realized there’s something more to making films.

What went into the planning and the actual staging of what we see in The Other Munch?

I don’t ever plan anything. [Laughs] The only thing I knew was that there were places we would go to. Joachim and Emil did the rest. I think that’s a very interesting angle into any artist: visiting the places where he or she works. The fascinating thing about going to the places where Munch painted is that it’s his universe. If you look at his paintings, they’re about his humanity or his pain or his moments in life. If you go to his house, it’s just 100 meters around. That’s the contrast. Art is this general, universal thing. The making of art comes from an intimate, concrete place.

After our first session together on camera during filming, I went to do this radio thing. When I talk in that kind of environment, I don’t think about people listening in so I just talk. I talked about working with Joachim and how I felt about talking about Munch, and the gesture becomes so big. You wonder: “Can we really talk about the biggest things about life and art?” I felt a bit of shame doing it. The stupid thing is that it was radio so, of course, Joachim was listening in. But that’s also part of what we did in the film because we opened up to each other in relation to what it is to make art. To me, that’s a constant rollercoaster. It’s very, very hard. It’s always, “Can you back that up?” if you say something. “Can you really do that? Can you say something grand about life and about art? Who are you to say that?” To me, that’s the bravery of Munch. His first painting—a masterpiece—was when he was just 22 years old. It was a great painting, but at the time, people who saw it laughed at it. His sister’s dying in the painting. He spent one year and put everything he had into it, and people are laughing? That’s difficult. It’s also interesting at the same time.

Were you finished curating the exhibition by the time you were making the movie?

No, that was all happening at once. It all came down to when we could meet to film.

How much of Munch’s work did you actually look at inside the vault? I know there was a show in New York not long ago at The Met Breuer, which, too, to some degree, put emphasis on Munch’s later, under-seen work. But there was literally no overlap between that exhibit and your curation. It just speaks to the sheer volume of work that Munch produced.

That was the starting point. They asked me to curate a Munch exhibition because I’m a writer who writes a lot. That’s a kind of connection. Then I went down to the vault and saw everything. It’s a basement where you pull out six-meter panels that are filled with his paintings. It was just so much stuff that I hadn’t seen before, and they didn’t look like Munch either. We know a version of Munch because he’s so well known for The Scream and a few other paintings, so I thought I’d make an exhibit of all the works that we haven’t seen to try to get a better understanding of him as an artist. What was he interested in? Where did he want to go with it? His work that we all know are well known because they’re so incredibly good. There are other works that are not that good and that’s why we haven’t seen them. [Laughs] But there are qualities in those under-seen paintings that are incredibly interesting. That’s what I tried to do with the exhibition: show Munch like you’re seeing him for the first time—without those masterpieces. There’s not one masterpiece in there, which was a great challenge and incredibly satisfying to do. I spent a lot of time in that museum. With this film included, it was like living Munch for two years. It was really great.

There’s this notion about “late style” art. Edward Said wrote an entire book about this idea that artists and writers produce a different kind of work later in life. I wonder how much of that was on your mind when you were putting the Munch show together.

I think what I like about his late-art is that he’s just trying—simply painting. He’s not looking to create a masterpiece. It’s all about the process that he’s in. You receive those pieces like it’s the life of the painting. It’s like when you read Proust—you’re in the life of literature. It’s as if his paintings were on the floor and people were walking on them and he didn’t care. There’s no interruption between life and art. I think that’s what he did and it’s wonderful. It’s just a way of life, and then there are the masterpieces.

You wrote about ice skating in The New York Times. You wrote about something as everyday as ice skating and it didn’t have to be anything more in the context of a novel, for instance. Joachim makes that comparison between you and Munch: you’re both “just doing it.”

That was kind of the worst thing that happened: that he would make any parallel between myself and Munch. No—I never think about that. I was almost shocked by Joachim and his theory about my work relating to Munch at all. I never use myself as any measurement. It’s the exact opposite: It’s about yourself being in it and disappearing completely, and what comes back is a desire to create something. That’s what you get back from looking at Munch as much as we did, I think.

It’s always interesting to look at the cross-pollination between different forms: filmmakers drawing inspiration from literature or musicians drawing inspiration from paintings. Here—a filmmaker is creating a documentary about a novelist who’s curating a Munch show. The expressive limits and the possibilities of each form is implicit in The Other Munch.

I’ve thought about Joachim’s films through Munch’s paintings to draw parallels. For instance, there’s a pose in many of Munch’s paintings that are very pained: a man looking away or a man in the scene not taking part in it. My favorite Munch painting is called Ashes. It’s in a forest and of a man looking down with a woman standing there. It’s an incredibly powerful image. I was thinking about Oslo, August 31st in relation to that. The film is about that. All the people are trying to connect, but he disconnects. He turns away. That’s something I took from the film.

When you write, how does your intuition and memory co-exist in the work?

When I wrote about rational things that I experienced myself, in my last book especially—this is very unprofessional—I was crying while writing. I sent that to my editor and he said, “There’s nothing there on the page. It’s all inside of you.” So I did it again, even though it was incredibly painful. I sent that to my editor and he said, “There’s still nothing.” I managed to do it a third time. To be able to do that and package it so other people can read it, you need a distance and do things that are maybe not as close to you. That’s the skill you need for writing or filmmaking. It’s a very strange thing. Intuition is what brings you to a certain place, but the actual transformation of turning stored memory into something that other people can understand requires distance.

With the film and the exhibition, you take the varnish off Munch and restore him in a new light. Is there anyone else who you’d be interested in “reinventing” in a similar fashion?

I always wanted to do something about Knut Hamsun, who’s a very well-known writer in Norway. He’s not as well known in the rest of the world. He’s my favorite author and incredibly interesting. He was also a Nazi during the war so he’s very controversial. Everybody hates his politics, but everybody loves his writing. How does that happen? How is it possible that he writes so tenderly about people and about his characters, but then he has this aggressive, horrible way of talking about politics? That would be a great interview. Also, it’s very interesting and great how he wrote about America—he was here when he was very young—because he was so raw and energetic about it. He was very critical, though. There are so many things about his life that are interesting.

Have you considered doing a book on him?

I have been thinking about it, yeah.

Just how much does your “Norwegian-ness” come into play when you’re exploring Munch? Would you arrive at very different conclusions being from anywhere else?

Probably. [Laughs] Joachim and I talked about that. Also, it’s been a hundred years since Munch painted. It defined for us what it is to be Norwegian and Norwegian artists in a way. It comes from him somehow. You can’t turn away from where you come from or the culture to which you belong. We’re immersed in it. We know Munch so well. He’s the only great artist we have.

Munch left behind a lot pieces that are so raw as to appear almost unfinished.

Unfinished work is very difficult. I think it’s easier to make peace with that in painting than with writing. The most obvious parallel is The Scream. If you look at that and consider what else was being painted at the time, it’s incredibly radical. That painting takes away space and it’s immediate. You don’t see that kind of immediacy in other paintings from that time. I know Munch read a lot of Dostoevsky. If you compare Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, everything is described with Tolstoy. With Dostoevsky, it’s just bits and pieces, but there’s also this incredible intensity in it and the intensity is the thing. So Dostoevsky would be the obvious parallel. The last thing Munch did the day he died was reading Dostoevsky in the afternoon. He died two hours later. He read him throughout his life. I’m absolutely certain that he learned from Dostoevsky somehow what he wanted to do.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments