This is the most unsexy story. I wish I could give you a Richard Burton story filled with debauchery and drinks.

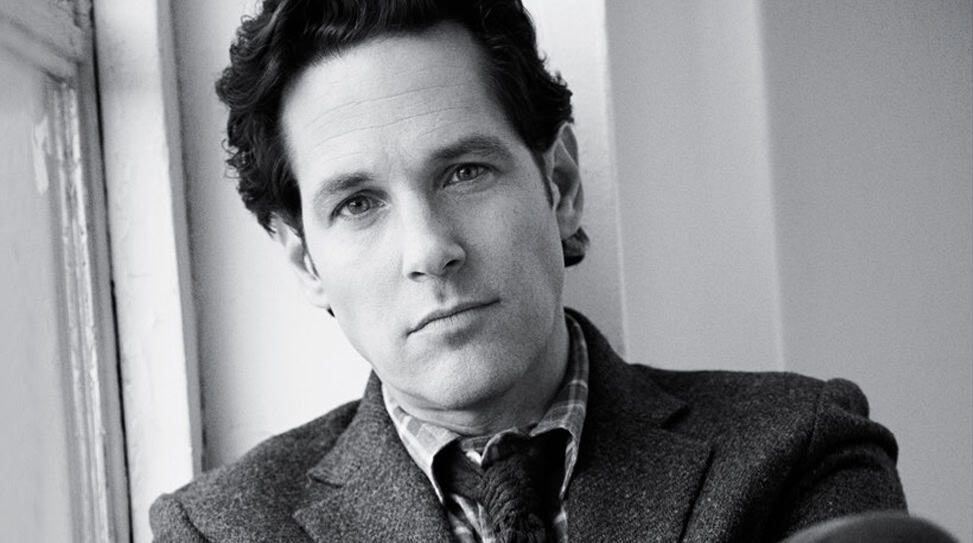

Paul Rudd has firmly established himself as one of Hollywood’s leading funnymen with such films as This Is the End, This Is 40, Knocked Up, Anchorman, The 40 Year Old Virgin and Forgetting Sarah Marshall. And to think, this is the same guy who first blipped on our radar playing Alicia Silverstone’s tightly screwed stepbrother in Clueless, which was over a decade ago! A lesser known fact is that the chameleonic 44-year-old—noticeably well-preserved for his age—doesn’t have much of a comedic background, a trait that ties together Apatow’s other pupil. Rudd’s background is in theater and he’s known just as much for his dramatic acting chops off screen.

Loosely adapted from a little-known Icelandic film called Either Way, David Gordon Green’s Prince Avalanche is a quietly moving, oddball comedy set in 1980s Texas following a devastating forest fire that ravaged 43,000 acres of woodland. Two weary blue-collar workers, Alvin (Paul Rudd) and Lance (Emile Hirsch), are assigned the Sisyphean task of repainting the yellow lines on the highway. They work, they bicker, they camp. Ultimately, it’s a film about two aimless souls that breathes with real cinematic expansiveness. Far from an embellishment, Explosions in the Sky’s triumphant post-rock provides the soundtrack, which draws out the correct dosage of emotions.

Prince Avalanche is now playing in select theaters.

How did this project come about? Who made the first phone call?

It came about because David [Gordon Green] called me. He and I’ve been friends for a long time. I met him when he had just finished George Washington and we were at a film festival. I always wanted to work with him because I think he’s great. He told me about this park not very far from where he lives that was ravaged by a huge wildfire and he really wanted to film something there. He wanted to make a cool character piece and go out there to shoot for a few weeks, and see what happens. We could kind of do it on our own terms because it would require a small crew and treat it as an experiment, really. I was just so down with that and it sounded like a lot of fun. Also, it seemed like a different thing than what I normally do.

How small was the crew?

It was something like fifteen people? These were people that David had worked with before. Tim Orr was the cinematographer and he shot all of David’s stuff. Christof Gebert was the sound guy and he even worked on David’s commercials. We had some interns from Columbia Pictures and Craig Zobel, one of the film’s producers, was part of the whole North Carolina collective and he brought on some of his students.

You guys shot this super fast.

In sixteen days. That’s one of the great things about being in one location. It’s not a lot of time, but it was enough time because it never felt rushed. It never felt like we were in jeopardy of not getting stuff. If we suddenly had an idea about something, we would shoot it anyway. We were able to shoot big chunks of things without having to worry about lighting and setting up for coverage. That was kind of nice. We were working a lot though with long days and there was no downtime. We shot this in a town called Bastrop in Texas, which is where Richard Linklater lives. It’s about 45 minutes outside of Austin. Since we were using one location, we could shoot the film in sequence, which is rare. That doesn’t happen often.

Did you and Emile [Hirsch] know each other prior to working together? There’s great on screen chemistry here.

I didn’t know Emile going into this. This was the first time I’d met him. We didn’t really have rehearsals. The first scene is when we actually started getting to know each other. That weirdly comes across when you watch the movie because we’re becoming more and more familiar with one another. I shouldn’t say we didn’t have time off because we couldn’t shoot when it got dark. As soon as the sun came up, we would start shooting. We were exhausted by the end of the day, so there were a lot of early bedtimes. Occasionally, we went to grab beer and burgers with the crew since we were a small group. We were up early each day. This is the most unsexy story. [Laughs] I wish I could give you a Richard Burton story filled with debauchery and drinks.

What was your early impression of David’s idea for the movie?

The idea that we were going to go around and do something as an experiment on our own terms, not really knowing if it would even get distribution, was what seemed fun about it. I thought the idea of painting traffic lines was cool even as a metaphor. The forest fire that ignited David’s idea for the movie was huge. I mean, it did like 26 miles of damage or something crazy like that. This was national news. People’s homes were destroyed and it made for a very chilling landscape. David actually went out to see it. A friend of his told him he should see it for himself and he did. Everything was ash. He thought it would be a very interesting place to film something in. Then another friend told David about a film he had seen at a festival called Either Way. Since David already wanted to explore a character-driven two-person story, he decided to put his own spin on that film. The characters in the original were painting lines, so that’s where that came from.

Instinctively, did you find it necessary to go back and watch the original?

I never thought about doing that. Maybe in part because it was in Icelandic? [Laughs] I didn’t know if I’d be able to take in such intonations and things. But I was curious about the film and wanted to see what had inspired David in the first place. In the end, I figured I would be creating my own take on the guy anyway. There are things that are different in the movie as it is.

Since you’ve known David for a long time and Emile had known David for quite a while as well, does that affect the creative process at all? Are you guys perhaps more open and honest with one another regarding the material?

Well, this was the first time that I actually worked with David. We’ve tried in the past to get movies made early on, but we were unsuccessful in getting the money to make these weird little movies, especially the one that we had at the time. I always had a sense that I would like working with David. I felt like we would speak a similar language, you know? I knew a lot of the things that would make David laugh or make me laugh. I sometimes feel as if we’re laughing at some idiosyncratic, banal kind of thing that isn’t even funny, but happen to lock in on. I loved working with him. He likes to be surprised and he could care less if we say what’s written on the page. He doesn’t care where you stand. I really trust him as an artist. I just listen to him and go with it.

Did you have any idea that the film would look quite this good while you were shooting?

I figured it was going to look pretty because we would be shooting in a spectacular setting. I already knew that Tim was an amazing cinematographer. I knew it would be atmospheric and lyrical. I knew Explosions in the Sky would be scoring and I think they’re amazing. Regardless of story or anything else, I knew it was going to look beautiful and sound really pretty.

How much of the film was improvised?

There was certainly some improvisation. The script was there and some things were very rigid while other things were left completely open. The scene where I stumble on that woman’s scorched house and she’s giving me a tour, that wasn’t in the script at all. In fact, that woman had lived in that house. She wasn’t even an actress. In character, I just started asking her questions and everything she said was what she was really feeling, and we made her a character in the film. We were able to do things that you wouldn’t normally be able to do in most productions given the nature of the process. That particular scene informed other scenes like the one where I’m walking around in a shell of a house and feigning this domestic life, which was written with a comic angle in the script. After meeting the woman, none of us felt like it was funny. Stuff like that was left open and served us better as a blueprint.

That woman captivated me and I had no idea that she was a civilian.

She kicked all of our asses. [Laughs] She was the real deal. She’s an amazing woman. With every word she spoke, it felt like she was about to burst into tears. When she says, “Sometimes I feel like I’m digging through my own ashes,” it’s like, oh my god! It’s so intense and it’s just the way she felt. Everything she owned and collected in her amazing life is suddenly gone with the fire. What does she have to prove who she is? It’s the kind of thing that you can’t really wrap your head around until it happens to you. It was hard to come face-to-face with the emotional destruction and personal chaos that the fire caused as opposed to just the landscape, which we had been living in for a week. It made a real thing even more real. If you’re listening, you know where to take your emotions. It didn’t seem like we should force anything and try to be funny here or sad there. I didn’t even think of the film within any kind of genre. It has its poignant moments, but I think a multitude of different things coexist with one another.

Outside of what the film lets on about Alvin, how much prep went into creating a backstory for yourself, if at all?

Sure, the more you know about the person you’re playing, the better job you’ll do, knowing the details. You also learn about that stuff as you go along. Sometimes you get a job and it’s like, we’re going to start next week! Sometimes you have a month to work with. I had a little bit of time with this and I did try to piece together some kind of history for Alvin. Whether any of those details are actually in the movie is irrelevant as long as I know what they are in delivering the performance.

How do you navigate your career nowadays? You must have so many options.

For good or bad, I’ve heard people mention the “one for me, one for them” approach, but I don’t have a conscious trajectory in the same way that I haven’t said, in the past several years I did a comedy and now I have to do something really dramatic. Maybe it’s stupid that I haven’t been doing that. I don’t think in terms of scale. I think in terms of what I like and sometimes those things don’t fit into a box or are commercially obvious. That said, I’ve been able to work on big studio movies that I love and aren’t shitty. Some of them are shitty. [Laughs] I can give you a few DVDs. My background isn’t in comedy and I’m not a comedian, but I work with a lot of people that went through Second City or Groundlings and I’m a huge fan of sketch comedy. I always gravitated toward comedy. It’s just not my background. I went to theater school and do plays on the side. I don’t know if I have what it takes to be funny in the way that those guys are.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments