We conceived Samsara as a guided meditation based on the themes of birth, death and rebirth.

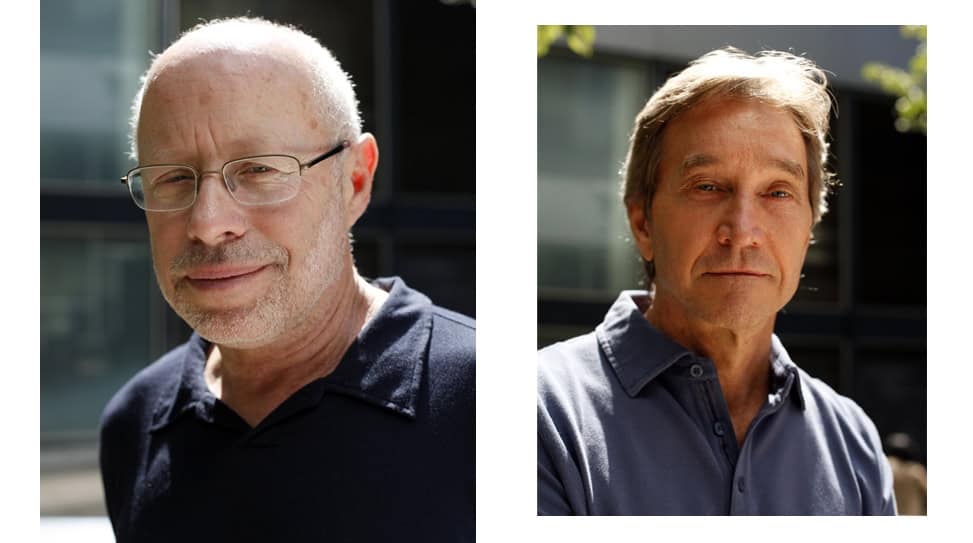

Samsara reunites filmmakers Ron Fricke and Mark Magidson, whose award winning films Baraka (1992) and Chronos (1985) brought a new visual artistry to theaters. “Samsara” is a Sanskrit word that means “the ever turning wheel of life” and it serves as the point of departure for the filmmakers on their search for the elusive current of interconnections that runs through our lives.

Filmed over a period of 5 years in 25 countries and photographed entirely on 70mm film, Samsara transports us to sacred grounds, disaster zones, industrial complexes and natural wonders of our world. By dispensing with dialogue and descriptive text, Samsara subverts our expectations of a traditional documentary or travelogue. It encourages us to make our own interpretations, inspired by mesmerizing images of unprecedented clarity and transcendent music that juxtaposes the ancient with the modern. Expanding on the themes explored in Baraka and Chronos, Samsara shows how our life cycle mirrors the rhythm of the planet.

Anthem sat down with Fricke and Magidson to discuss the genesis of their latest project, why it’s becoming increasingly difficult to gain access to certain locations (from the mundane to the miraculous), and what they hope viewers will take away from watching the film.

Samsara is now playing in select theaters.

Let’s start with the basics. Where did you two meet and how did this collaboration begin?

Mark Magidson: We met through a mutual friend back in the early 80’s, so it’s been nearly 30 years. My god. [Laughs]

Ron Fricke: It’s funny how time flies.

Mark: Ron wanted to make an IMAX film and he was building a camera. It was the first of the three cameras we used. So we got together and that particular film turned out to be Chronos, which was finished in 1985. And then we wanted to do a longer film with Baraka. IMAX features in those days were like 30 or 40 minutes in length. It was a different model than the stuff you see in IMAX these days. They were in museums and they had educational content. We wanted to approach a longer format and that became Baraka in 1992.

Ron: Mark is an inventor and an artist. We’re just in total sync in terms of what we want accomplish. It’s a good match.

How are the duties divided up? Are you more of the techy guy, Ron?

Ron: We both do a little bit of everything.

Mark: Ron is very creatively involved in the projects.

You must get so exhausted by the end of each film. These are huge undertakings that take years and years of patience and perseverance.

Ron: There was a big break between Samsara and Baraka. It does take a big chunk of your life. Baraka was a 3-year project. Chronos probably took 2 years and Samsara took 5 years. You have to find space in your life to work out everything else that you feel like you need to work out. If you want to have a personal life at all with family or whatever… [Laughs]

Could you walk us through the pre-production stage? What sort of conversations did you share?

Ron: We explore themes.

Mark: We conceived Samsara as a guided meditation based on the themes of birth, death and rebirth. We knew we had the mandala sand-painting to open and close the film. We create it and destroy it at the end, so that was a real guide for structuring the content. The film is really about the flow and the interconnectedness of things. We were really only able to see that come together in the edit. We edited the film without music or sound. We made little blocks of content and let the images guide everything.

For something like the mandala sand-painting, were you able to do multiple takes if it didn’t come out looking the way you wanted it to?

Ron: It really depends. In some cases you only get one shot at it, especially on the time lapse stuff where your running the camera all night long and you end up with 15 seconds of footage. That kind of footage is really valuable and hard to come by. You get 1 shot at that or maybe 2. With portraits, you can get a couple of takes, but we’re not out there shooting everything in sight. It’s very focused.

How difficult was it to gain access to some of these locations?

Ron: A lot of things in this film were harder than Baraka—

Mark: Everything was difficult.

Ron: [Laughs] The world is changing. It’s harder to get access to factories and such compared to when we made Baraka 20 years ago. People are just more sensitive or more concerned about how they might appear.

Mark: Getting government access takes a long time. We worked on the Mecca sequence for a year before we actually got the go ahead. We got there and it almost fell apart on us. There are a lot of things that are tenuous, but hopefully you can pull it off. We’ve been doing this for a while now. We have a lot of experience and things usually work out.

Ron: In the U.S., no one wanted to give us access to anything. We couldn’t even go into people’s kitchens. None of these food factories would let us in. We were able to get into the factories in Asia and they were proud to show us how their operations worked. It’s tough.

I’d imagine it will only get worse as time goes on.

Ron: Probably. It probably is.

What were some other places that you couldn’t get access to? What was on your wishlist?

Ron: Well, there’s this 1 country… [Laughs] North Korea. We almost got in there. We wanted to film these massive performances that they do annually with tens of thousands of performers in a big stadium. They’re all dressed up in wild outfits, this Busby Berkeley kind of a look.

Mark: Busby Berkeley on steroids, really.

Ron: We tried to get access to that for 2 years and we couldn’t utlimately. I think, at least partly, us being an American crew made it more difficult.

How do you propose something like that? What channels do you have to go through?

Ron: For North Korea, I met with Bill Richardson, the governor of New Mexico who was the ambassador of North Korea. He wrote a really great letter for us to the UN Mission here in New York for North Korea. We got pretty high up the food chain over there. But we ended up getting terrific access to a martial arts academy in China to sort of fill in what we couldn’t get in North Korea. We had 7,000 kids doing martial arts. So there were shots in the film that we didn’t know we would get and it worked out great. You just hope that things will balance out. Things can fall apart, but you get a lot of good breaks too.

How long did it take to edit Samsara?

Ron: About a year. We had a couple pick-up shoots, which was built into the schedule just because we knew from making Baraka that when we shape the film, we’re going to need certain things that we don’t have. You look at the totality of the film and sometimes you need to go back out and find the missing pieces.

Was it a challenge shooting on film?

Mark: Well, there are challenges that Ron can tell you about. It’s really great to shoot on film. That’s all I’ve been doing.

Why was it important to shoot on 70mm film?

Mark: We don’t have main characters or any dialogue. It was the essence of the images that we were after. There’s nothing like 65mm or 70mm film. It has that kind of fidelity. We were really fortunate to be able to go out and work in that format. Shooting film doesn’t really slow you down. You just need to know where you want to put that camera and where you want to put it next. It’s not like shooting digital.

Ron: When you’re going into 25 countries, you want to bring back footage in a format that will hold up. There’s nothing like 70mm film stock–still! We took the film into a digital environment afterwards and output as digital. On Baraka, we outputted to film. It’s sort of the best of the old and new technologies.

I forgot to bring this up earlier, but how much of the shots were staged? How much intervention was there on your part to get the kind of shots you wanted?

Mark: It was really about getting what was there. We did some small lighting for the portraits. We wanted to be as unobtrusive as we could be. Sometimes people forgot that we were there.

Ron: There are few things that needed to be arranged. We contracted for the sand-painting to be created by the monastery in India.

Mark: The performances were set up.

Ron: The three Bali girls at the beginning of the film, for instance. The prison dance was set up.

Mark: The guy in the suit with the clay was also a performance.

Ron: But they’re doing what they would naturally do. We’re not telling them what to do. We’re simply filming what they do.

The guy in the suit with the clay was interesting in that it’s quite dramatic and different compared to all the other sequences. I didn’t quite know what to make of it in terms of how it fits into the film as a whole. What does it mean?

Mark: The performance is all about the shadow that’s in all of us. It’s the part of us that we don’t want anyone else to see.

Ron: That’s what he’s expressing in the performance. We found him on YouTube.

It’s a very powerful performance. It’s almost disturbing.

Mark: We just put him in a suit and put him behind a desk. He normally doesn’t perform that way. So to address your other question, we manipulated that a bit.

Maybe it’s too soon to ask this, but are you thinking about your next undertaking?

Mark: We’re on break now!

Ron: [Laughs] We’re still recovering. There was so much space between Baraka and this film. We’re not getting any younger here, so if we do something it better not be 25 years from now. You just need a break in-between these kinds of projects.

Mark: The world is a big place. There’s a big, epic world out there.

Watching something like Samsara makes you feel so small, yet feel so connected to the world. What do you want viewers to ultimately take away?

Ron: That’s a really good insight when you say it makes you feel connected to the phenomenon of life going on now at this time in history. There’s no translation and no language barriers. There’s no nationality barriers in the film. I think that’s really appealing on some level. You want to feel that connection to everybody. It sounds a little corny, but we all want to feel that. You see in the film how people live differently, worship differently and yet it’s all similar.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

4 Comments

the fed never made any mistakes their agneda was always the same rob america rob the poor n give it to the rich $800 B in onme go to wall str crooks, trillions spend in wars the poor pay with blood n tax money for the ams manufacturers n oil barrons to make their Trillions while over 40 M americans live bellow the poverty line n millions in tents cars caravans any shelter they can this is Criminal all this to make theelite even more richer? they got the usa in this mess not ppl

pot shel navi zaam!

That’s a really good insight when you say it makes you feel connected to the phenomenon of life

Hello Mr. Fricke,

Let me introduce myself; my name is Christine Cain and I’m an intern with Nettwerk Music Group and I’m reaching out to you on behalf of our management team. One of our Grammy nominated clients Mike Posner is interested in working with you on a project for his upcoming album. His management team was hoping to be able to connect with you directly. Is there a direct contact, email address or social media platform that you can provide to us?

Thank you in advance.

Christine Cain

Intern-Nettwerk Music Group