She's empowering because she takes no prisoners. She isn’t trying to please anybody. It was very empowering to play someone who literally didn’t give a fuck.

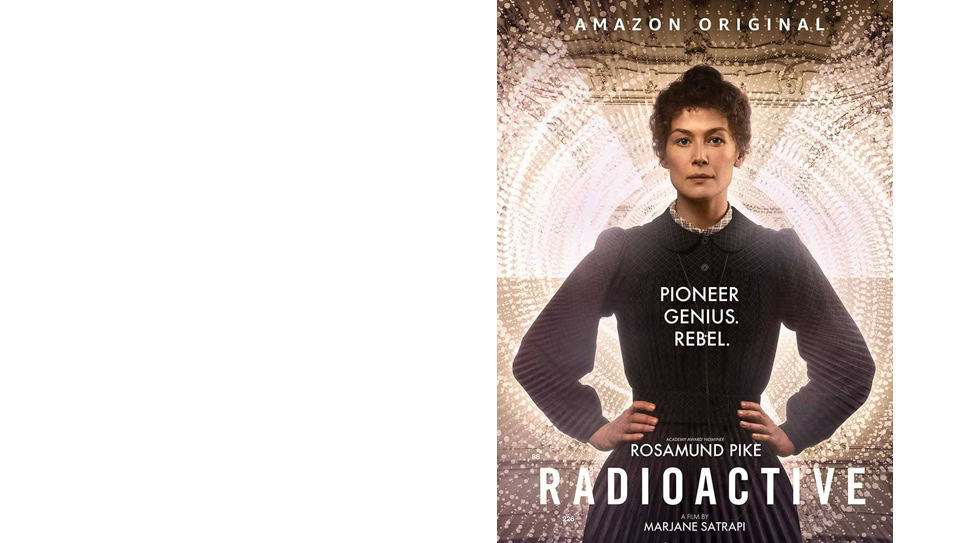

Most of us know, at best, that Marie Curie cast a long shadow. Marjane Satrapi’s Radioactive is a story about the moral conundrum at the heart of life-altering human achievements—that profound, fruit-bearing discoveries can, at the same time, fuck things up for humankind in a really bad way. Where science is concerned, the Polish physicist and chemist is one of the hard cases. Does the number of lives saved by Curie’s pioneering work outweigh the number of lives lost? Maybe, maybe not. It’s a heady question with no easy answers, but one nonetheless she had to wrestle with time and again throughout her storied life. Curie was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, and less than a decade later, the first anyone to win two. Her discovery of radium, polonium, not to mention the love of her life, are the atoms energizing Radioactive’s century-spanning breadth.

It’s 1934. Curie (Rosamund Pike) is rushed on a hospital gurney, in her final illness. Her life is flashing before her eyes and her story begins to unspool in flashback. At the end of the nineteenth century now in fin-de-siècle Paris, Curie (then still known as Marie Sklodowska) is a medical student at the Sorbonne. Right away, we see her headstrong independence, unwavering sense of self-worth, and tenacious drive. This is something that, because she’s a woman, makes her an unpleasant eccentric in the eyes of her male colleagues. She demands rather than asks the academy’s board to respect the integrity of the laboratory where she is carrying out her work. Their response is to throw her out. She proudly continues her experiments in a cold garret. A fellow scientist and like-minded outlier, Pierre Curie (Sam Riley), jostles her on the street one day. They share an interest in radioactivity. They thumb their noses at the establishment. They make groundbreaking discoveries together, which catapults them to global fame, during which time they fall in love and have children, including Irène (played by Indica Watson as a tot and Anya Taylor-Joy as a young adult), who would win her own Nobel Prize for developing artificial radioactivity.

Throughout Radioactive, we periodically jump forward into the future, way beyond Marie’s mortal coil, to explain, all seer-like, the reverberations of her genius. The first leap is to Cleveland in 1957, where a doctor tests a new radium gun on a young boy suffering from cancer. Later, we visit the cockpit of the Enola Gay in 1945 as the pilot obtains permission to drop his payload—history’s first atomic bomb. The A-bomb over Hiroshima in the last days of World War II follows. Then we’re on to Operation Nougat, a series of nuclear tests conducted in Nevada beginning in 1961. Finally, young firefighters go to their deaths in the bowels of a flaming Chernobyl in 1986.

Back in Paris, there are comparatively, yet no less penetrating, micro-upheavals. Marie struggles with the slight of being nominated for her first Nobel Prize only when Pierre declines to accept the honor without her. Following his death in a freak accident, Marie weighs the great losses in her life—including her mother as a child, which has instilled in her a life-long fear of hospitals—tying them to her research. With her continued lethal exposure to radiation, she forges ahead in the name of science at a personal cost of her own. This sacrifice is a key distinction for Marie, who in one instance confesses to her daughter that her life of science—with all its successes and failures combined—“have brought me very little happiness.” It’s one that Pike plays unquestionably well.

As was the case with her Golden Globe-nominated performances in Matthew Heineman’s A Private War, another biopic about war correspondent Marie Colvin, and David Fincher’s Gone Girl as Amy Dunne, the conniving “cool girl;” and José Padilha’s 7 Days in Entebbe in which she played a fanatical German terrorist; the true power of Radioactive lies in the steady hands of Pike—a startlingly fine actress. Pike refuses to let her other Marie be the cold face pulled from history books nor the fragile heart that emerges from a private life of great personal loss. All of them dynamic women in the grip of forces they cannot control, Pike’s portrayals are not easily forgotten.

Radioactive will premiere on Amazon Prime Video on July 24.

I understand that Marjane [Satrapi] sent you a little package to entice you with this project.

Well, she sent me the graphic novel with the script. It’s unusual to receive a novel like that, which is pictures—Lauren Redniss’s drawings are very evocative and transporting. I knew from a quick glance that this wasn’t going to be a conventional biopic. Certainly, I knew it wasn’t with Marjane Satrapi attached to direct it. She also later, when we met in Paris, handed me another package, which was the grief journal that Marie Curie kept in the weeks after her husband died, which is one of the most moving, passionate outpourings of love that I’ve ever read in my life. I thought, “Wow. This difficult, abrupt, quite stern woman had these rivers of emotion running through her,” which she kept private, necessarily, because it wasn’t to her advantage to display any of that in a work context. Work, for her, always came first. It was for me two poles of this person: the keen, deciphering, rigorous scientist and then this passionate lover. I found them very, very appealing contradictions. Well, maybe not contradictions, any scientist would argue. I think the guiding requirements for being a scientist are curiosity and passion.

Marie Curie is no doubt an extraordinary individual, and you have embodied your share of intriguing women. Sort of mirroring how she was conflicted in her dealings with science versus the unknowable such as the afterlife, how much is the craft for you intuition-based versus applying practical techniques that you’ve discovered over the years? Simply, do you think there might be some science to acting?

Hmm… I think it’s a combination. I think you have to change this sort of muscle memory of your own body on a cellular level. I think the experience of the character you have to not just read about, you have to take them in. You have to ingest them. You have to experience even the ones that are not depicted in the film. You have to read about them, and not just know about them on a factual level. You have to let them in to the point that you could feel them. For instance, when her mother died of tuberculosis and she felt that she had failed her, that has to be internalized as a lived memory, not just known about as a fact in a biography. This is how I believe. Then on a daily basis, hopefully all of that work will have been done and the person is just allowed to flourish. All of that has gone into your cellular memory, I suppose, and I think that’s true, more and more, certainly with playing real people. I watch this film and I feel things. I feel things as though I’m watching something that I lived, rather than something that I acted in.

Were there aspects to Marie Curie that you found a bit difficult to wrap your head around, either because it was very far from you or simply because she’s messy, which we all are?

The only thing that I really struggled with was why she had this affair with Paul Langevin, her student. I just didn’t get it. I couldn’t understand why she did it. I didn’t want her to do it. [laughs] Sometimes, you have a character where you don’t want them to behave a certain way.

That’s very honest.

I sort of put that off, really, of thinking about that bit in the script. I didn’t want to get to it because I believed so wholeheartedly in her marriage to Pierre. Then suddenly, I got it. It was like a flash of understanding. I suddenly realized that it wasn’t about falling in love with him. I felt that the biographies have quite often misattributed that affair as something really significant in her life because of all the media attention it attracted. But actually, I think she had that relationship with him because he was the only person who could fully understand what she’d lost. He was the one other person who was as close to Pierre as she was, be it on a scientific level. He really understood Pierre’s mind. As soon as I thought of it like that, I could play it.

There are dualities at play in other corners of Marie Curie’s life. For instance, the positive implications of her work also meant unimaginable devastation. Hiroshima. Chernobyl. But one aspect of her that doesn’t seem to stand in opposition to anything else is how hyperaware she is of who she is. It must be empowering to play that essence of somebody.

It is, and she is an empowering person to play. She’s empowering because she takes no prisoners. She isn’t trying to please anybody. You realize that there’s a lot of time and effort and a lot of emotional waste in worrying and fearing about how you’re being seen all the time, which is unfortunately only getting more intense, I think, in our modern life. It was very empowering to play someone who literally didn’t give a fuck. And yes, you could overanalyze that and say, “Well, you know, that was just a posture as well.” Fine. But I do believe that her main drive was science and everything else got in the way of it. She was very, very good at not being diverted from what really mattered to her. In our modern world, it’s so easy for us to be diverted away from our own truths because of worrying about appearances or how we’re seen or how we’ll look or any of those myriad concerns.

I love the visual of her actually sleeping with a vial of radium. The glowing emerald light illuminating her face is of course beautiful and striking in itself, but crucially, it’s this very idea that she is so resolutely absorbed in her work that’s encapsulated in that one image.

Right! And when Pierre dies and you feel that her brain is exploding with radium and how that’s conveyed. Marjane’s mind is fierce and Marie Curie was fierce. I just love all of that, too. Also, radium caught the world’s imagination. I mean, literally. At one point, Pierre talks about all those letters they’re receiving from people who want to use radium for this and that and whatever. The world just fell in love with it. It was this glowing element that looked so beautiful. It was sort of like finding Tinker Bell in a vial, you know? They wanted it in everything—in face cream and toothpaste to make your teeth shine. Luckily, it was so darn expensive that, actually, all the things that claimed to have it in, did not. Most of them.

I tried to recall when I first might’ve learned about Marie Curie. It had to have been in grade school. How much had you known about her prior to this project coming into your sphere?

I think the way that science is taught in school, it doesn’t really overlap with history. You do learn about some scientific discoveries and who discovered them, but it doesn’t come with the sort of vivid character portrait like this, you know? So I didn’t know. I understood her as being connected in some way with cancer therapy. I didn’t know she discovered two new elements on the periodic table, and then there’s another element called curium that was actually named later, after her, in her honor. I didn’t know she won two Nobel Prizes and that she had a daughter who also won a Nobel Prize. I mean, I just didn’t realize. I hadn’t thought about radioactivity as we understand it, stemming from a discovery in, basically, a lean-to shed in Paris at the end of the nineteenth century.

I really think we could benefit from bringing movies like this into classrooms because you open up the opportunity for emotional attachment to learning. What are your thoughts on something like that?

I’ve seen it with a few children. I took pieces of the movie into my son’s school—not a whole movie. I also took a whole lot of glow sticks and taught them about polonium, which glowed blue, and radium, which glowed green. Right after, I think they’d probably taken away the fact that Marie Curie invented glow sticks. [laughs] It basically, as you can imagine, turned into a kind of dark rave in the school hall. But I agree with you. I know that Amazon is going to put out some teaching materials to go alongside Radioactive. I think we do want this to be a film that’s discovered and used to promote science.

How different was it to take somebody on like Marie Curie, in ways that are maybe different from Marie Colvin in A Private War? It’s the magic of acting and actors, I suppose. You find them somehow.

Yes, obviously with Marie Colvin there was a responsibility of really creating an embodiment that truly felt like her and conveyed her mannerisms, her voice, her walk, her laugh—everything. With Marie Curie, there’s lots of still images but very few pieces of video footage. So I had a lot more freedom in that sense.

From the outside, you appear to be somebody who goes all in. Not only because you’re dedicated. I would venture as far as to guess that it’s out of compulsion, as an inherent quality that you naturally possess. It’s like when you said years ago that you weren’t interested in social media because that would require a lot of your attention to do it right. You didn’t simply shut the door on the idea of it.

Well, and then in lockdown, I started exploring it because I had realized that it’s a sort of necessary tool. But again, I put a lot of thought into everything I do.

Oh I know—you can tell!

So dashing off a post really isn’t in my nature because I care. I care about words. I care about images, you know? If you stop caring about words and images, then you don’t put enough respect into the power they have, I think. There are so many words and so many images out there. It boggles my mind. But yes, in lockdown, I had a bit more time to think about it. I can see that it’s a rabbit hole. I started doing things like recording some poetry because I had to sort of make it truthful and honest to who I am, which is probably not the idea. [laughs] The whole thing is probably supposed to be conveying a version of myself that I’m not, really. It doesn’t make me feel good, to be honest, to convey something that I think I would like the world to see that isn’t the truth. It gives me a bit of a sick feeling.

Radium crippled Marie Curie’s bones and ultimately took her life. It was quite literally her life’s work. Not to sound over-the-top with this, but is that something you can relate to with your love of acting?

I think it has a cost, for sure. I think all these experiences and these traumas that we live, or let in very deeply, are stored in the body somewhere. Yes. I mean, I never get confused. In my mind, I know I’m not Marie Curie or Marie Colvin, but I don’t think my body doesn’t believe that I’ve suffered horrendous grief when I’m asking it to believe that. I think when the hormones, the adrenaline, the cortisol flood your body in a performance, that goes into some destruction of your cells, for sure. I have no doubt about it. You can have a kind of post-stress response long after a film is made, actually. Not every film! [laughs] I’m talking about when the lives get bigger and they’re real and there’s a bit of a cost. There are films where you get away scot-free and it was just a lovely thing to make. You can play a small part in a harrowing film and get away relatively unscathed. But I think with these big lives, yeah. It is my life’s work. I’ll do it until I’m 80 or 90 or for however long they let me keep doing it.

Kee, where are you from? I mean, you’re American, but are you Chinese?

I was born in South Korea. I’m actually calling from there right now.

Oh are you? Ah, so you’re Korean. I’m working with Daniel Henney on The Wheel of Time.

Oh right! Yeah, Daniel is big over here. His face is on absolutely everything. McDonald’s…

I know. I’ve been sort of teasing him about his product line. [laughs] His face masks. No, he’s lovely. We’re having a great time together.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments