More and more, I want to direct because I’m seeing things that I don’t want to have happen. I’m a little bit frustrated as an actor.

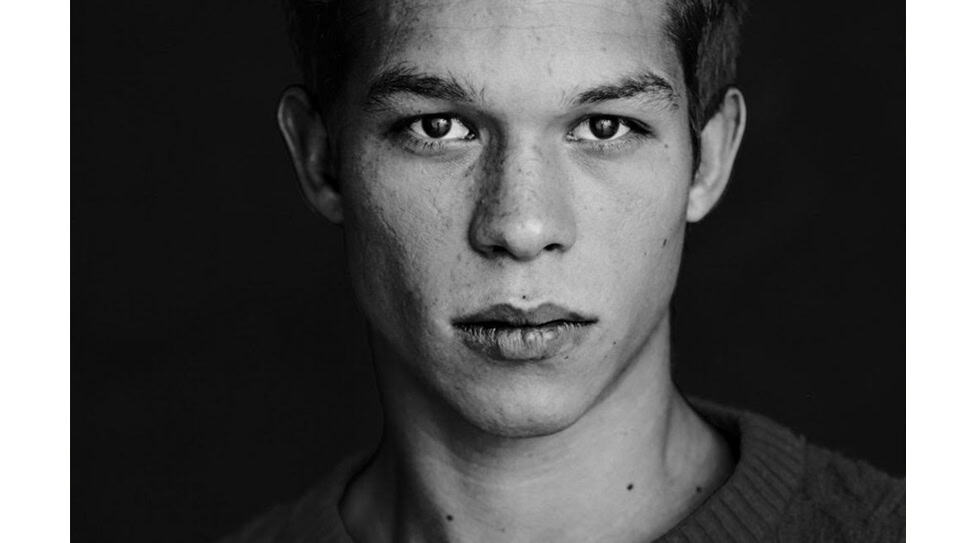

28-year-old newcomer Sandor Funtek had quite an auspicious start on his path to a career in acting. After being discovered by filmmaker Josée Dayan at age 19 to star in the TV movie To Die of Love in 2009–a remake of the 1972 Best Foreign Language Film Golden Globe nominee Mourir d’aimer…—his four-year silence was followed up by Abdellatif Kechiche’s Blue Is the Warmest Color, which picked up the coveted Palm d’Or at Cannes. In 2015, Funtek was back on the Croisette with Jacques Audiard’s Dheepan—that film would also take home the Golden Palm.

Anthem more recently saw the actor’s star continue to rise in Susanna Nicchiarelli’s Nico, 1988, detailing the turbulent final years in the life of Warhol Superstar Nico, aka Christa Päffgen. In the film, Funtek portrays Nico’s son, Ari, whose iconic father Alain Delon always denied paternity.

Next up for Funtek is Sarah Marx’s L’Enkas. The story centers on Ulysse (Funtek) who, upon release from jail, returns home to a deeply depressed mother (Sandrine Bonaire) with bills that never stop piling up. Here’s an idea: Ulysse conspires with a friend to sell “ketamine water” out of a food truck at various raves. L’Enkas world premiered at the 75th Venice Film Festival last week.

For more information on L’Enkas, head on over to the official La Biennale Di Venezia page.

First of all, I loved Nico, 1988. You must be really proud.

It was a special experience. I met the real son of Nico.

I was going to ask you about him.

His history—his story—is so sad. He was in an asylum for 30 years. He suffered a lot in life. His father [Alain Delon] always denied paternity. He has these scars everywhere.

Did you meet him before or after making the movie?

I talked to him twice before making the film, and the director [Susanna Nicchiarelli] didn’t ask me to. She said, “If you want to see him, you can. But I won’t make you do it.” He’s quite sick. He had two cerebral attacks so he speaks with a lot of difficulty and he can’t walk. I wanted to go see him because I wanted his blessing. It’s quite a tricky story to tell. It’s still strong in his mind. It’s still something really deep for him.

Before we get deeper into discussing your work, can you tell me what you were doing before you started out on this path with acting? How did you get into it?

Well, my parents are artists. My father was an actor. He came from a really small village in Hungary and he made it there. My mother was an actress also at that time. They met on a movie.

They must be so proud of you—to see you succeeding in their field.

They are. My father only speaks Hungarian and my mother only French. And they made me!

I hope so.

[Laughs] It happened through a lot of difficult times—through money problems—that all artists deal with in their lives. So seeing that, I didn’t want to do any sort of art in the beginning. I was traumatized by money. I wanted to go to a regular school. There was a moment when I was living in the South of France with my father for 4 years, and when I went back to Paris, I met the right people who put me on this path. I met a casting director and got my first part in a TV movie at 19.

This was To Die of Love.

Yes, of course. It was a remake of a movie from the ‘70s. I had a friend who was involved with the film. He was a musician. I was getting into a lot of trouble at the time. I was starting to go in a bad direction—doing bad stuff. I didn’t know what to do with my life. Then I started hanging out with my friend and he put me on this journey. I met an agent who sent me to auditions, and after I made Blue Is the Warmest Color, it started to become real. I wanted to do this job, finally.

You had a crazy start: Your first theatrical film was Blue Is the Warmest Color, which won the Palme d’Or. Two years later, you did Dheepan, which also picked up the Palme’Or at Cannes.

Yes, of course, even though they were two small parts. At the beginning of the journey, I actually did want to act because it came easy to me. It was quite cool because I was meeting a lot of people from different places and from different social circles. It was a beautiful realm of interesting people. So I started to think of it as the holidays, you know? You go for one month with people that are quite interesting and funny. The patience came a few years after when I started to really do it. I really wanted to do it and acting was starting to become more important to me and I wanted to take it really seriously. At the beginning, I saw it as a game.

What do you learn from directors like Abdellatif Kechniche and Susanna Nicchiarelli?

Oh, they’re totally different. [Laughs] On Blue Is the Warmest Color, Abdellatif was a different kind of director. He’s the kind of director who manipulates his actors. He’s looking for reality. He’s looking for the truth in everything. So you’ll work on a scene for three days—the same scene, doing the same stuff—and you don’t ever know when it’s good or not. At that moment when you’re starting to get tired and angry, then something happens. He’s looking for that moment. So he doesn’t really trust actors. He’s not an actor’s director. He’s more a guy who’s looking for the truth in everybody. Through blood and tears, he’s going to get what he wants. In an honest way, he’s less human to work with than someone like Susanna who trusts actors and trusts that they can learn the lines. With Abdellatif, it was only improvising—only trusting moments and situations.

What do you prefer?

I prefer everything. I love feeling like I’ve learned something. When I go back to my hotel room or when I go back home, if I didn’t learn anything, I’m starting to get sad and angry. When I really learn something, even if it’s a bad experience, I feel totally cool. That’s what I like.

Was there added pressure because you’re playing someone who’s alive to watch it?

It was tricky. I didn’t want to disappoint him. Playing somebody who already died is quite easy—“He died!” [Laughs] But playing somebody who’s still alive—who still suffers from that kind of history—was quite tricky. We got so close because there was some kind of alchemy when we met. There was something really normal and not something fake like in the film industry. I didn’t want to use him. I didn’t want to mock him. I wanted to be sincere and imagine his history. I didn’t want to make a documentary.

So now you’re back at the Venice Film Festival. I’m so looking forward to L’Enkas. How did you get involved with this lead role?

I played a really, really little part in a movie called The Last Parisians and the guys who made that [Hamé Bourokba and Ekoué Labitey] have been rappers for 25 years.

They wrote L’Enkas, didn’t they?

They did. They wrote this one with the director [Sarah Marx] and they also produced it. They have a pretty cool story. They don’t “ego rap” or anything. Their lyrics are really strong and deep and political. I’ve known them for 15 years. We grew up in the same neighborhood in Paris in the 18th district. It’s an underground art district where everyone meets and shares stuff. I think this district also inspired me to act because you’re circled by artists and want to become that. When I met them, they became mentors to me. And when Sarah brought L’Enkas to them, they told her, “You have to meet Sandor Funtek.” When Sarah and I met, I didn’t audition. We just met and one hour later she called me and said, “Yeah, man. It’s you. It’s you.” It was a very nice experience.

It’s a special project. Also, it’s a really hard and really tough project. In the same way with Abdellatif trying to find the truth in me, they knew me for 15 years so I can’t lie to them. When I was starting to fake it or act, they were talking to me like, “Oh man, you’re doing shit.” [Laughs] “Let’s try to make it real.” We had many producing issues and everything, but they’re fighters—warriors. It’s crazy. They made it with nothing. Really nothing.

You have a lot of charisma. But in terms of the projects, it’s understandable why people would be curious. You go to Cannes and then go back to Cannes. You go to Venice and now you’re back again. What’s your secret?

[Laughs] It’s a lucky thing. I don’t know… It’s been 9 years that I’m doing this work. I made many, many, many short movies. I’m training a lot. My mom helps me, too, because she knows actors. She helps me with English. I think things are happening really slowly, but I’m getting ready to do some big parts—big things. I’m not having extraordinary success at the moment, but things are happening like I want them to happen.

I saw that you’re directing your own short film right now called The Virgin of Lost Causes. How far along are you now?

I just met the transgender actor in her Hungarian village, which is also my village with my family and everything. I have to find a Hungarian co-producer. The problem is, in Hungary, these kinds of movies are not financed because it’s a very, very tough moment with politics there. They’re really racist and homophobic as well. I have to find a way to do it myself as much as I can.

So is filmmaking another trajectory you’re committing to?

More and more, I want to direct because I’m seeing things that I don’t want to have happen. [Laughs] I’m a little bit frustrated as an actor. I’m starting to get frustrated. It’s only been 9 years that I’m doing it so I have to experience it a little bit more and I love it, too, but I really, really feel that I want to direct.

The title is very interesting.

The Virgin of Lost Causes, yeah. It’s because at the beginning of the movie it takes place in Paris, in my district, where you have this church called Sainte-Rita. This little chapel brings around gangsters, hookers, transgenders and everything, to pray on Thursday nights. So it stars them. They still have some spirituality and something really close to God, even if God didn’t make them as they wanted to be, you know? So it’s quite a symbolic title.

Can I ask you how you ended up at Madonna’s 60th birthday in Marrakech?

Of course you can! [Laughs] It was her very, very closest friends and her family. Everyone was there. It was a wonderful weekend. Everybody was so nice. We were partying in the desert. It was totally friendly, cool, and beautiful. She’s so inspiring.

What’s your favorite Madonna song?

[Laughs] What’s my favorite Madonna song?! It’s the one where she’s the cowboy…

“Don’t Tell Me.” I love her because she doesn’t give a fuck.

That’s right. She’s a really intelligent woman. She’s fascinating. She works her ass off. When I meet her, I always feel stronger. She’s so open-minded. She never has enough. She has to see new things. If you’re a huge star and an icon for decades like her, of course there’s something special in those characters. She’s a queen. As you said, she doesn’t care. She says what she wants to say.

Do you think you’re going to feel very changed in 5 years time?

I don’t know… I’m trying to live in the present. I don’t know what I’m going to do in 5 years. That doesn’t mean anything to me. Maybe in 5 years I’m going to live on a small island in Thailand!

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments