When I read the script, my wife and I just had a son and he was maybe a month old. It hit me in the gut because I hadn’t known that kind of love before.

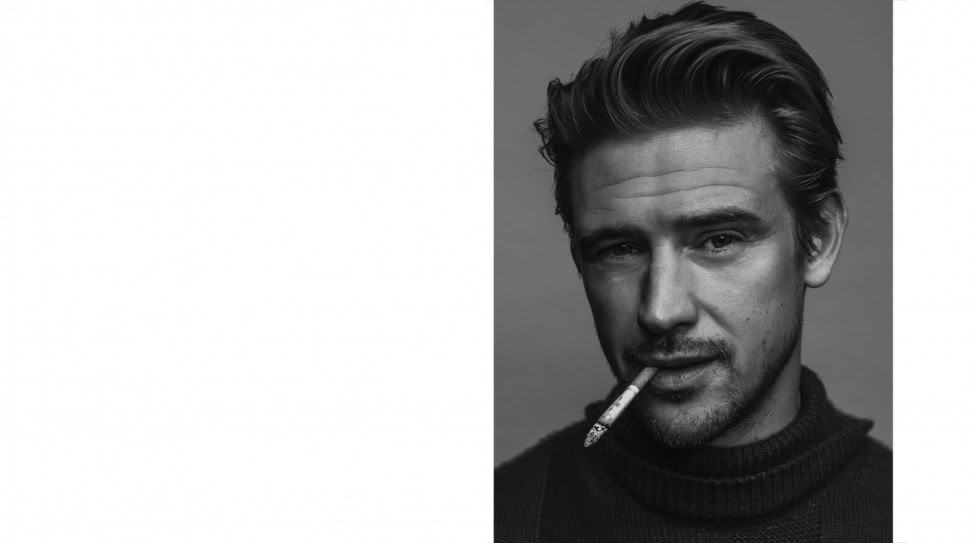

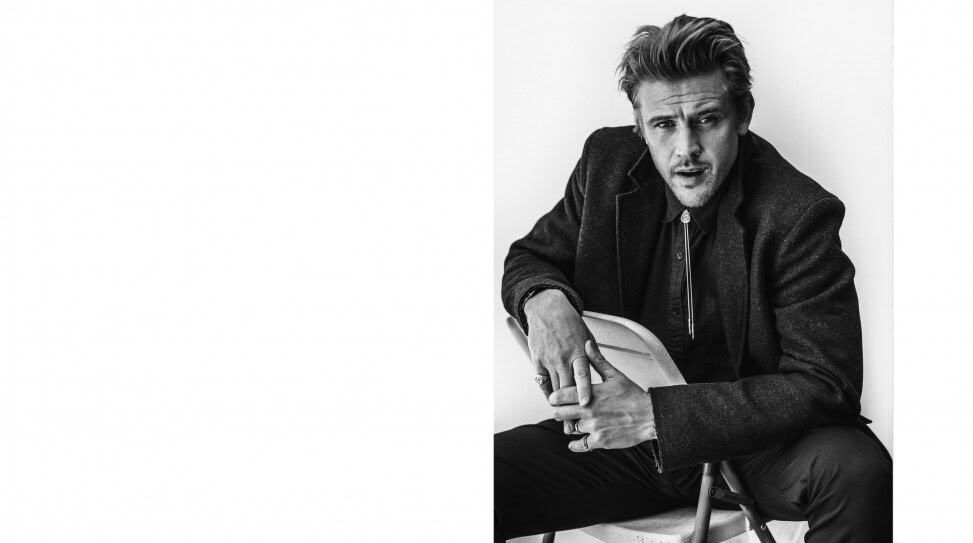

Photography by Reto Sterchi

Styling by Lisa Nguyen @ The Industry Artist Mgmt

Grooming by Benjamin Thigpen @ Statement Artists using Oribe and ReVive Skincare

Special thanks to Robbie Sokolowsky @ Tribeca Journal Studio

Jim Mickle’s In the Shadow of the Moon opens on Philadelphia 2024. Inside a high-rise office building, the phones go unanswered, a siren is heard blaring outside, and through the shattered windows a tattered American flag enters and falls out of frame, defeated. But this is not the American flag—there are five octagrams in place of fifty stars. This is, in fact, the symbol of a so-called Real American Movement, a white nationalist call to arms spearheaded by a fringe militia club leader. “Strike back, fellow soldiers,” the deranged manifesto reads. This is the dystopia we fear we’re careening towards both on and off-screen, but if you can believe it, Mickle’s genre-bending psychological thriller is rather depoliticized considering such an ambitious backdrop.

This is instead a story about obsession—the all-consuming quest of one man from 1988 to 2024 with the narrative leapfrogging in nine-year increments. Boyd Holbrook, in his meatiest role to date and his best since James Mangold’s Logan (2017), turns in a polished performance as police officer Thomas Lockhart, who is so hungry to rise the ranks that he begins tracking a serial killer that mysteriously resurfaces every decade, in a case assigned to his no-nonsense superior played by Michael C. Hall. But when the killer’s crimes begin to defy all scientific explanation, his obsession with getting at the truth threatens to destroy his career, his family unit, and his sanity. So how does our protagonist, the Real American Movement, time travel, and the film’s murder mystery thread intersect? We won’t go spoiling that here. All we can reveal is that this man’s quest was fated.

Anthem shared an afternoon with Holbrook in New York City for an exclusive photo shoot and an interview to discuss obsessions, the chain reaction that is our lives, and his actor’s process.

In the Shadow of the Moon is now available to view exclusively on Netflix.

Have you seen the finished film, Boyd?

I have, yeah.

Netflix hooked me up early so I’ve given it several viewings now. You’re fantastic in this. Obviously, this is one of those movies where the less you know about it going in, the better. Jim [Mickle] offers thorny commentary on where America is currently at and where we might be headed. It skews very dark in that respect.

It’s definitely rooted in reality. I think the more liberal the country becomes, the stronger the right wing is reinforced so it creates more separation in that sense. We’re living in a very frenetic world.

At the center of it all is a truly obsessed individual. Tunnel vision, blinders—that whole thing. It must’ve been really exciting to explore that, especially through decades of this man’s life.

Absolutely. As an actor, it’s really attractive to play the different time periods. It’s also attractive to track the arc of this character’s life, starting out as this very driven and engaged individual who then becomes an obsessive maniac. Tracking the arc and playing that was what drew me to it most.

I was actually binging Mindhunter when I first got around to watching In the Shadow of the Moon. They informed one another in my thinking about the work of detectives. Cold cases must be so devastating to them, knowing they might never get solved in their lifetime—if ever. How did you personally relate to that?

To be quite frank with you, I’m a very obsessive person in general. When it comes to acting, I will work for hours and hours and hours and hours on end until I’ve cracked something. You go down this rabbit hole of scripts and characters. What’s the entry point? How can I find this person in myself? I really related to the idea of obsession in my love of acting—I love cracking that mystery. A lot of it pays off and it helped with this role as well. I think with every film you have to find a different recipe. You can’t use the same gimmicks and tricks that you used on the previous films. You gotta figure out a new approach.

By the time we get to 2007, Tommy is pretty deranged. He’s living out of his car, chasing this mystery. He looks like he could use a good wash. Michael C. Hall expresses his concern to you: “You’re chasing moonbeams while your own life got away.” You were once quoted saying that you like to play strange individuals.

I like to play something that’s completely foreign to me because that’s a bigger stretch for an actor. You go on quests and learn something new about yourself to get to that place. You have to overcome those hurdles. The strangeness is also uniqueness—it’s what makes them special in our society. I think quirkiness and individuality is what people refer to as strange or odd. Those are usually much richer and much deeper characters than, say, the anchoring lead characters—the classic leading male characters. They usually don’t have a tremendous amount going on because they have to anchor the thing. So I like to find those characters that have a real specificity to them.

One thing that I find is so rare about Moon is that, going into it blind, I had no idea what I was watching because it kept transforming into something else. I remember watching the 1988 chapter and it feeling very reminiscent of David Fincher’s Se7en, and then all vestiges of that vanishes in 1997. The genre is never broadcasted to you. Was that your experience in reading the script for the first time?

For me, I think it just goes back to the idea of obsession because I’m embodying the character. It all reflects how much this guy loves his wife and his job. Everything is rooted in that. When I read the script, my wife and I just had a son and he was maybe a month old. It hit me in the gut because I hadn’t known that kind of love before. Just imagining my character’s circumstances, it would drive anyone to really examine themselves. That was my takeaway and, simplistically, it’s how everything is grounded in that.

It’s an unremitting truth that fatherhood changes you and that must extend into acting.

It’s beyond true. Selflessness. People can tell you and you can read all the books about it, but until you take in somebody or have a child—it’s crazy shit. My wife had a complicated birth, which was very scary for us. Luckily, we were okay, but again, if that unfortunate circumstance were to happen, it’s a tailspin.

I just realized I brought up Fincher twice with Mindhunter and Se7en. You worked with him on Gone Girl. You’ve worked with some rad filmmakers: Steven Soderbergh, James Mangold, Shane Black, Terrence Malik… Your first credited role was in a Gus Van Sant movie, which is nuts. In your experience, what makes a director great?

Whether it’s a director or an actor—really, anybody who’s a part of the movie—there’s a learning curve that we all sort of have to endure. It’s the fundamentals of any craft. Knowing they’ve gone from novice to expert really draws me in because there’s so much experience and intellect involved in that. Also, protection is a part of it. So all of that combined with a great story, your chances of pulling off something that you put so much time and effort into feels like it pays off, whether it’s a financial success or not. That’s what I’m looking for. For me, failure is a huge part of my work. In preparation I have to, I guess you could say, get it wrong. But getting it wrong gets you to the place of figuring it out and getting it right. There’s a humbleness to that. People talk about getting the jitters or being nervous. I know that when my stomach drops, whether it’s excitement or fear, I’m in for a ride. I know that I’m in for a good experience—something’s gonna happen—and I don’t look at it as a negative. I look at it as a positive.

Did you shoot this in chronological order?

No, and it was the most difficult thing I’ve ever done. There were 34 days, but I think I’m in every frame of every shot. We would jump around eras. We would do three eras in a day. Just sitting there getting all this makeup work done and keeping mental track of all this stuff to plan, to perform, and to create the arc of the character was difficult. It was challenging just to keep my mental stamina up and perform and then also take into consideration the age of the character and where he is in his life. There were so many things going on. Again, this was probably the hardest thing I’ve done to date. You brought up all the great filmmakers I’ve worked with and I think that was all just preparation to be able to do this.

Do you remember filming the pig car crash scene? It’s operatic. It’s wild.

That was real, dude. That was me getting the shit beaten out of me. [laughs] It was well worth it. Jim has really good taste and makes excellent choices. He’s super playful and makes everything a lot more fun.

I checked out an interview that Jim gave to Collider and he said he was most nervous about the old age makeup because there’s nothing worse than getting that wrong, especially in dramatic situations where you’re trying to sell big emotions. He also revealed that you weighed yourself down at the end.

You spend so much time daydreaming and rehearsing this stuff trying to work smarter, not harder. I thought this guy should be heavy at that period in his life, not in terms of physical weight but just with emotional baggage. You can call this stuff tricks or whatever they are, but they service you in a really good way. Obviously, it was a fucking terrible idea because it was August and I was wearing 20 pounds on my chest underneath the clothes. It worked, but it was a lot. [laughs] It was a lot to give a little.

I’ve come to learn that you do a deep dive in your preparation. You research. You have a voice coach when that’s required. You have an acting coach. Did you work with Terry Knickerbocker on this film?

I work with Terry Knickerbocker on absolutely everything. Terry Knickerbocker is a pillar in the acting community and a pillar in my life. He’s a huge mentor. I can’t say enough nice things about him. I have a voice coach named Gerry Grennell who’s also an absolute legend. He worked with Heath [Ledger] on his Joker role. It takes a village, in my opinion, to really come up with all of this stuff because acting is a two-man sport. It’s not, “I’m the best in the world!” You have to elevate the other person and the other person has to elevate you. That’s the way it should work as much as it possibly can. So yeah, I do like to do a lot of preparation. A director has so much going on. The less he has to worry about you, the better, in my opinion. I like to come in where I’m good to go even if they don’t give me direction. But hopefully I’m working with amazing, talented directors so there’s a collaboration. I’m certainly open to that.

You’re super thoughtful and meticulous in your approach to the craft. It makes sense that you once apprenticed for a sculptor, Fernando Mastrangelo, and created your own works and had shows in New York. You come from an artful place. I also know you wanted to become an architect at one point in time.

I did so many different things in my early 20s. I was just really trying to figure out what fit me best. There are so many different mediums that I love, sculpture being my favorite. I wasn’t a great student as a kid, but I was always in these talented and gifted programs for drawing and art and stuff like that. We didn’t have a lot of theater or anything like that so I didn’t really discover cinema until I was 16. I didn’t get into drama school until I was 25. I went to film school first. So I’ve done a lot on my path towards figuring out what fits me best. Hopefully, I’ve found it. I’m about to do my fifth film this year and that will be it. I’m writing some scripts that I’m producing so I’m manicuring those along. It’s been really hard to juggle that obviously with my son being a year and a half. We’re still in the weeds, which is chaos. [laughs] I’m really looking forward to being on the road a little less, but I’m just on such a kick right now that I keep on riding that wave.

You sent a script you wrote to Gus Van Sant at the beginning of your career, wanting him to direct it. Instead, he gave you your first role in Milk. I’m dying to know what that was about.

I wish I had made it. I had a chance to direct it a couple of years after that, but I wasn’t really ready. I ended up making a Sam Shepard short film. If you decide to direct a film, it’s probably a good two years of your life that you should commit to it exclusively. You shouldn’t also be acting or doing anything else. That script was called Uncle Sam. It was set in Appalachia around where I’m from. Gus was super sweet and really helped me out. I guess you could say that I cut my teeth a little bit on Milk. It was the first film set that I’d been on. I had to leave acting school, which was a big issue because we were encouraged to finish school and then start working. That way you kind of know what you’re doing? [laughs] But you know, you take it when you can get it.

The short film you directed is Peacock Killer, based on a short story by Sam Shepard.

That’s the original title of the short story from Sam Shepard’s 1974 book Hawk Moon. You should read his books, they’re phenomenal.

So we can expect a feature from you down the line, on the directorial front?

Yeah, yeah. Maybe in two to three years. There are a couple of things I’m thinking about doing. I just don’t like to get too comfortable.

Maybe this ties back to Moon, which is so much about a chain reaction of events. You were discovered by a modeling agent in your hometown and you were very successful in that. You also had moxie: you put yourself through school. Did it feel like the cards were stacked against you growing up in Appalachia? It’s extremely rural where you’re from.

Yeah, there’s coal mining. I’ve got grand respect for my father who’s worked in that industry for 30 years. My prospects weren’t looking very good out of high school. I worked for UPS and went through their Earn to Learn program. I was unloading planes at midnight and going to school at 8 A.M. Then I dropped out of college. I would say that I have a bit of a psychotic drive, which helped me. [laughs] I’m joking about that. I was like the Energizer Bunny. You punch me in the face and I keep getting back up until I get tired. And it’s so funny that whole model-turned-actor thing. I was working at a theater company and somebody offered me an opportunity to move to New York, so I took that. I used it as much as it used me. I took the money and ran. I got into school. I got myself out of being dead broke. I had a thousand bucks when I moved here and I made that last for 11 months. I’m persistent.

Look at you now. What a journey. Do you go back to Kentucky?

Absolutely. I go back as much as possible. I’m really close to my family. Appalachia is beautiful.

You have other acting projects on the horizon like Robert Rodriguez’s We Can Be Heroes—that one reunites you with Pedro Pascal.

It’s maybe not what you’re expecting. It’s a kids’ film, kind of in the vein of Spy Kids. It’s super funny. I play this oblivious, airhead superhero. Hopefully it’s something for my son to watch.

You also have a FX series called Platform. I remember seeing a picture of you and Jon Bernthal on your Instagram. I’m excited for that one.

That’s gonna be super heavy. Let’s not give too much away, but B.J. Novak, the writer and director, wrote one of the most flooring pieces of writing I’ve been blessed to be involved with in a long time. It’s extremely timely in terms of what’s going on in today’s culture. I’m very excited about it.

A Conversation with Sean Wang

A Conversation with Sean Wang A Conversation with James Paxton

A Conversation with James Paxton

No Comments